Many are the inventions attributed to the Chinese people in ancient times that are directly related to their art, and those are the one about to talk in this article. They were known for keep the secrets of their skills in each trade well protected for millenniums in with no foreigner could obtain them. Many inventions related to the art in China were invented hundreds and even thousands of years before the Western civilizations. The invention of a method to print with ink over paper made from rice paste was one of the most significance. Noteworthy was also the elaboration of beautiful ceramics with practical use, but when the porcelain was discovered, were famous for their perfection in its design and detailed decoration. They kept for centuries for themselves the secret of how to do porcelain vessels. For the Chinese, it was not only an economic issue, but also a way to honor family traditions. Its artisan tradition, with attention to detail and hard work turned their developed objects into exquisite works of art. As soon as the products of this ancient Chinese culture are known in Western civilization have high demand, mainly for its high quality, plus an aura of mysticism about the unknown Eastern civilization that captivated immediately the imagination and desire of upper class in the West to own so wonderful and exotic goods. The secret of making porcelain for example was protected by the Chinese authorities with the death penalty to those who dared to reveal it, even it was forbidden for the foreign dealer visit the interior of China and only in specific commercial places designated near the coast they could obtain the goods. They have always been cautious about the commercialization of their products tending to rather be economically self-sufficient, but they had to adapt to new economic necessities’ to increase its monetary flow due to the growth of the population, creating specific products to export in line to the Western taste. Equally protected was the method for the production of silk fabrics which was discovered in China 5000 years ago. The famous Silk Road was developed by Western countries to obtain coveted merchandise, its soft and light texture reached high appreciation and demand that were compared with the value of gold and even magical attributes were also conferred to the silk. It is well known that the Roman Empire citizens did care so much for this fabulous fabric and imported such huge amount that textiles trade protection laws was decreed by the Roman authorities. Chinese were masters in the use of wood for construction, furniture and artistic decorations. In China the elaboration of various wooden objects becomes also a trade which passes from father to son for generations; as other trades did. Bamboo and precious wood objects were developed for centuries by them with practical use and detailed decoration, some with very difficult intricate designs, among them hand fans, jewelers boxes, containers for incense, as well as diverse architectural elements such as doors and windows in which not a single nail is used, but putting instead overlapping wood pieces with a pretty clever technique that has tested for centuries the efficiency of their innovative constructive skills using wood. In Chinese art is often used lacquer; a clear layer of the SAP of the trees used to add beauty and luster to objects made of wood which protects them from insects and the deterioration of climate. The western culture try to imitate in different ways the incredible finish the Chinese provide to their artistic objects some of which had up to sixteen layers of the lacquer. Lot of time, try and error efforts had to be endure by the western artisan’s until they found some decent approach using different techniques that offered a look alike lacked itch effect in their pieces. Although they had certain demand were very expensive due to the hard work and time consuming task that their technique require.

Gold and Ivory from Paris, Pisa, Firenze and Siena 1250-1320

The summer exhibition at Louvre-Lens – Gold and Ivory – highlights the wealth of artistic exchanges between Paris and Tuscany 1250 -1320

Between 1250 and 1320 artistic exchanges between Paris and the leading city-states in Toscana flourished. Thanks to exceptional loans from around twenty prestigious European museums, a new exhibition lifts the veil on the relationships between the major centres of artistic creation of the period: Paris, Firenze, Siena and Pisa.

The exhibition brings together more than 125 exquisite works: monumental statuary, gold background paintings, illuminated manuscripts, fine enamels and ivories. In particular, these works reveal the influence of French exponents of High Gothic style on the Tuscan sculptors and painters in the late 13 th century, within a region, which would become the cradle of the early Renaissance.

This exhibition at the Louvre-Lens is the first to examine this artistic interchange, which is of paramount importance to the history of art.

Paris 1250

In 1250 Paris was one of the largest European cities with nearly 300.000 citizens. It was also the capital of the Kingdom of France, home of Saint-Louis and a vibrant intellectual and artistic centre with a decidedly international reputation. With its great architectural sites (the Sainte Chapelle, the Lady Chapel at Saint Germain des Prés, the transept of Notre Dame) and the completion of the courtyard of the Palais de la Cité, Paris became the “capital of luxury”. Indeed, an abundant production of precious objects were produced there (illuminated manuscripts, ivories, goldsmithery), supported by an explosion of artistic commissions by the elite. Paris was the heart of what we now refer to as High Gothic. Paris was simply the ‘hot’ place to be.

Part of this repute was due to the architectural and artistic milieu, which developed in the wake of the building projects of the king. It has been claimed that Paris at that time underwent a development akin to what happened in Paris in the 19 th century under the direction of Haussmann.

Cider

Men grind grain while citizens of all ages prepare cider, one of the traditional beverages of the northern French province of Picardy. This painting and The River (on view nearby) are studies for the left and right sides of Puvis’s mural Ave Picardia Nutrix (Hail, Picardy, the Nourisher). Made for the newly constructed Musée de Picardie in Amiens in 1864, the paintings celebrate the region’s abundant natural resources and its idealized, distant past. Puvis’s decorations for the museum launched his career as a preeminent painter of murals for state buildings in France.

to experts illuminate this artwork’s story

#6012. Cider

0:00 RW Skip backwards ten seconds.

FW Skip forwards ten seconds. 0:00

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 audio. Here is a link to download the audio instead.

Artwork Details

Use your arrow keys to navigate the tabs below, and your tab key to choose an item

Artist: Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (French, Lyons 1824–1898 Paris)

Medium: Oil on paper, laid down on canvas

Dimensions: 51 x 99 1/4 in. (129.5 x 252.1 cm)

Credit Line: Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1926

Accession Number: 26.46.1

Inscription: Signed (lower right): P.Puvis de Chavannes

the artist (until 1893; sold on September 6, for Fr 10,000, to Durand-Ruel); [Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1893–1906; stock no. 3121; sold on February 3, 1906 to Hébrard for Wagram]; Louis-Alexandre Berthier, prince de Wagram, Paris (1906–8); [possibly Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1908–at least 1909]; [Galerie Barbazanges, Paris, by 1912–13]; [Turner & Gardiner, London, 1913; sold on March 2, with “The River” (MMA 26.46.2) for $28,000, to Quinn]; John Quinn, New York (1913–d. 1924; his estate, 1924–26; sold to The Met; cat., 1926, p. 13)

Paris. Durand-Ruel. “Puvis de Chavannes,” October–November 1894, no catalogue [see Riotor 1914 and Lemoine 2002].

New York. Durand-Ruel. “Paintings, Pastels and Decorations by M. Puvis de Chavannes,” December 15–31, 1894, no. 4 (as “Le Cidre [Project of decorative painting]”).

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. “Puvis de Chavannes,” 1895, no. 3 [see Price 2010].

Geneva. Musée Rath. “L’Exposition d’œuvres de MM. P. Puvis de Chavannes, Auguste Rodin, Eugène Carrière,” January 1896, no. 2 (as “Le Cidre [panneau décoratif]”).

Paris. Durand-Ruel. “Exposition de tableaux, esquisses & dessins de Puvis de Chavannes,” June–July 1899, no. 27 (as “Le Cidre,” lent by MM. Durand-Ruel).

Berlin. Bruno and Paul Cassirer. “Austellung von Werken von Edouard Manet, H.-G. E. Degas, P. Puvis de Chavannes, Max Slevogt,” October 15–December 1, 1899, no. 31 (as “Der Most,” probably this picture) [see Price 2010 and Echte and Feilchenfeldt 2011, vol. 1].

St. Petersburg. Institut Français. “Exposition centennale de l’art français,” January 28–?, 1912, no. 503 (as “Grande esquisse pour le musée d’Amiens,” lent by Barbazanges).

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “The Masterpieces of French Painting from The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 1800–1920,” February 4–May 6, 2007, no. 41.

Berlin. Neue Nationalgalerie. “Französische Meisterwerke des 19. Jahrhunderts aus dem Metropolitan Museum of Art,” June 1–October 7, 2007, unnumbered cat.

New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Rodin at The Met,” September 16, 2017–February 4, 2018, no catalogue.

Charles Yriarte. “Beaux-Arts: Six oeuvres de M. Puvis de Chavannes (Galerie Durand-Ruel).” Le Figaro (November 10, 1894), p. 1.

“Exposition de M. Puvis de Chavannes.” Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, supplément à la Gazette des beaux-arts (October 20, 1894), p. 252, as “Le Cidre”.

Paintings, Pastels and Decorations by M. Puvis de Chavannes. Exh. cat., Durand-Ruel Galleries. New York, 1894, p. 17, no. 4, dates it 1893.

“Der Kunstsalon Bruno und Paul Cassirer.” Staatsbürger-Zeitung no. 516 (November 3, 1899) [see Echte and Feilchenfeldt 2011, vol. 1], as “Der Most”; calls it an example of Puvis’s “correct” drawing and “academic” composition.

Roger Fry. Letter to Bryson Burroughs. March 31, 1909 [published in Denys Sutton, ed., “Letters of Roger Fry,” vol. 1, New York, 1972, letter no. 263, p. 319], reports that this picture and “The River” are available for purchase through Durand-Ruel.

François Monod. “L’Exposition centennale de l’art français à Saint-Pétersbourg (2e et dernier article).” Gazette des beaux-arts, 4th ser., 7 (April 1912), p. 323, calls it “Automne”.

René Jean. L’Art français a Saint-Pétersbourg: Exposition centennale. Exh. cat.Paris, 1912, pp. 59–60, finds the landscape in this picture and its pendant reminiscent of Corot.

“Exhibition: One Hundred Years of French Painting 1812–1912.” Apollon 3, part 1, no. 5 (1912), ill. between pp. 40 and 41.

James Huneker. Letter to John Quinn. March 13, 1913 [published in Josephine Huneker, ed., “Letters of James Gibbons Huneker,” New York, 1922, p. 154], congratulates Quinn on the purchase of “the various Puvises”.

Léon Riotor. Puvis de Chavannes. Paris, [1914], pp. 26, 66, mentions that two decorative sketches called “le Cidre” and “la Pêche” were exhibited at Durand-Ruel in October–November 1894.

B[ryson]. B[urroughs]. “A Recent Loan of Paintings.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 10 (April 1915), p. 76, states that John Quinn has lent this picture to the MMA; describes it and “The River” as studies for an 1865 decoration at the head of the stairway on the second floor in the Picardy Museum, Amiens, noting that the Amiens installation is one continuous landscape, intersected by a central doorway.

James Huneker. Ivory Apes and Peacocks. New York, 1915, p. 306, calls it “The Vintage” and dates it 1866.

James Huneker. Letter to John Quinn. March 26, 1916 [published in Josephine Huneker, ed., “Letters of James Gibbons Huneker,” New York, 1922, p. 206].

John Quinn, 1870–1925: Collection of Paintings, Water Colors, Drawings & Sculpture. Huntington, N.Y., 1926, p. 13, as “Le Vendage”.

Léon Werth. Puvis de Chavannes. Paris, 1926, p. 125, pl. 10, dates it 1879.

Camille Mauclair. Puvis de Chavannes. Paris, 1928, p. 162, erroneously calls it a sketch for the right side of the Amiens decoration.

Josephine L. Allen and Elizabeth E. Gardner. A Concise Catalogue of the European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1954, p. 79.

Charles Sterling and Margaretta M. Salinger. French Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 2, XIX Century. New York, 1966, pp. 225–27, ill., remark that this composition was originally incomplete at the lower left corner, corresponding to where the architectural elements in Amiens intruded on the actual decoration; note that this picture was finished and signed at a later date when it was no longer needed as a study and could be sold.

B[enjamin]. L[awrence]. Reid. The Man from New York: John Quinn and His Friends. New York, 1968, pp. 160–61, 197, 200, notes that Quinn paid $28,000 for this work and “The River,” making this his costliest purchase to date; erroneously states that it was shown in the 1900 Paris Exposition.

Richard J. Wattenmaker. Puvis de Chavannes and the Modern Tradition. Exh. cat., Art Gallery of Ontario. Toronto, 1975, pp. xxiv, 27–29, 58, 65.

Jacques Foucart-Borville. La Genèse des peintures murales de Puvis de Chavannes au Musée de Picardie. Amiens, 1976, pp. 58–61, fig. 13, dates it just before November 1864, suggesting that it was retouched in 1893.

Louise d’Argencourt in Puvis de Chavannes, 1824–1898. Exh. cat., Grand Palais, Paris. Ottawa, 1977, p. 64 [French ed., Paris, 1976, p. 67].

Judith Zilczer. “The Noble Buyer:” John Quinn, Patron of the Avant-Garde. Exh. cat., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution. Washington, 1978, p. 179, as “The Grape Harvest (Le Vendange)”.

Brice Rhyne. “John Quinn: The New York ‘Stein’.” Artforum 17 (October 1978), p. 59, notes that Quinn specified this picture and its companion be offered for sale to the MMA after his death.

Claudine Mitchell. “Time and the Idea of Patriarchy in the Pastorals of Puvis de Chavannes.” Art History 10 (June 1987), pp. 192–93, pl. 60, calls it a study for the left side of the decoration; discusses alterations Puvis made from an earlier drawing of the composition (Musée de Picardie) to our painting with its figures of an old man and woman looking at a young child; proposes that “as he worked on the canvas Puvis devised techniques to clarify the visual exchange between grandparents and grandson” to signify the cycle of life among the generations.

Aimée Brown Price. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Exh. cat., Van Gogh Museum. Amsterdam, 1994, p. 104 n. 2, under no. 38, refers to the “Cider” composition as the left side of the decoration.

Gary Tinterow. “Letters: The New Rooms at the Metropolitan Museum, New York.” Burlington Magazine 136 (April 1994), p. 241.

Katharine Baetjer. European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art by Artists Born Before 1865: A Summary Catalogue. New York, 1995, p. 434, ill.

Serge Lemoine, ed. From Puvis de Chavannes to Matisse and Picasso: Toward Modern Art. Exh. cat., Palazzo Grassi, Venice. [Milan], 2002, p. 547, fig. 5 (color) and ill. p. 545.

Kathryn Calley Galitz in The Masterpieces of French Painting from The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 1800–1920. Exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. New York, 2007, pp. 64, 248, no. 41, ill. (color and black and white).

Kathryn Calley Galitz in Masterpieces of European Painting, 1800–1920, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2007, pp. 74–75, 293, no. 68, ill. (color and black and white).

Aimée Brown Price. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Vol. 1, The Artist and His Art. New Haven, 2010, pp. 52, 222 n. 198.

Aimée Brown Price. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Vol. 2, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Painted Work. New Haven, 2010, pp. 99–100, 105, no. 129, ill., calls it “Le Cidre” or “Les Vendanges” or “Cueillette des pommes / Cider”; dates it about 1864, noting that the mural dates from 1864–65; observes that the colors in this picture are “lighter, narrower, and more subtle than those of the mural”.

Kunstsalon Cassirer. Ed. Bernhard Echte and Walter Feilchenfeldt. Wädenswil, Zürich, 2011–16, vol. 1, pp. 179, 196–97, 202–3, 213, ill. (color), as “Der Most”; identify it as in Berlin 1899; republish Staatsbürger-Zeitung 1899.

Caroline Elam. Roger Fry and Italian Art. London, 2019, pp. 47, 66 n. 93.

Art of Ancient Chinese civilization

Posted on November 18, 2014 5:44 pm by Elena 2 Comments

Art of Ancient Chinese Civilization

Art of ancient Chinese Civilization is very peculiar, distintive from others because Chinese Civilization is likely one; among most ancient civilizations that have particularly maintained a cultural continuity and philosophical cohesion throughout its history, thanks in part to its geography location that is unique, situated at the end of the Asian continent facing the Pacific Ocean, which allowed them to keep their strong culture pretty much intact, but thanks also to their way of life, which was very intimate keeping their distances from the influences of the outside world across millenniums. Even though few of the invaders along Chinese history could have diluted their way of life and Idiosyncrasy by absorbency, the Chinese choose to stick to their traditions and belief firmly, continued their devotion to nature and their ancestors, even when different religious believes were sustained in the country, as well as when invaders forced their violent ways in China. Chinese people keep as well their country, reliable on a self-sufficient economic, since traditional customs and artisanal trades knowledge pass from generation to generation among members of the families. Their art productions were a direct reflection of their particular believe and their philosophy of life. Particularly in early times, art also had social and moral functions. Witch the beginnings of the modern world in the XVI century was brought to them as well the effects of a huge wave of events that imposed important changes in the world. Chinese culture was also in certain way influenced by those changes and other internal issues, but this article would concentrate in ancient Chinese period art. Up to the Warring States period (475–221 B.C), the artistic representations were produced by anonymous craftsmen for the royal and feudal courts. It is thought that during the Shang and early Zhou periods the production of ritual bronzes was exclusively regulated under the authority of the court in which patrons design features were shared among specialists working in the various media and were remarkably uniform from bronzes to lacquer wares to textiles.  Chinese culture promotes and emphasizes a form of social life in their communities rather than give more importance to the individual lives of human beings, but underlines the importance of the relations between the members of a family or between the individual and their King or Emperor according to the historical period. In their efforts to confront the challenges of everyday life as society get their greatest strength using the gifts from nature and working very hard. Among the typical themes of traditional Chinese art there is no place for war, violence, the nude, death, or martyrdom. Nor is inanimate matter ever painted for art’s sake alone. All traditional Chinese art is symbolic, for everything that is painted reflects some aspect of a totality of which the painter is intuitively aware.Their society was more prone to secularism and respect for nature than devotion to omnipotent gods as it was certainly the trend in Western civilizations.

Chinese culture promotes and emphasizes a form of social life in their communities rather than give more importance to the individual lives of human beings, but underlines the importance of the relations between the members of a family or between the individual and their King or Emperor according to the historical period. In their efforts to confront the challenges of everyday life as society get their greatest strength using the gifts from nature and working very hard. Among the typical themes of traditional Chinese art there is no place for war, violence, the nude, death, or martyrdom. Nor is inanimate matter ever painted for art’s sake alone. All traditional Chinese art is symbolic, for everything that is painted reflects some aspect of a totality of which the painter is intuitively aware.Their society was more prone to secularism and respect for nature than devotion to omnipotent gods as it was certainly the trend in Western civilizations.  So far the history of Chinese civilization has been situated in the Valley of Yellow River in China; between approximately 5,000 to 4,000 BC in the ” Early Neolithic period “. New archaeological findings at Sanxingdui, a small village about 20 miles northeast of Chengdu in Sichuan province have uncovered objects dating from around 1200 B.C. There were two sacrificial pits containing hundreds of foreign objects never before found buried and hidden for 3,000 years,. Among them objects of gold, imposing human heads made in bronze, bronze with unusual shape masks, as well as some tools of stone and jade, showing how these early men already have certain skills that allows them to represent the elements that make up their daily lives such as viticulture, hunting and fishing. There are aspects of social coexistence represented with themes such as banquets and acrobatic shows, as well as its incipient world of mythology and religion. Today the Chinese people are learning much more about their own culture thanks to the multidisciplinary studies that are underway in this vast country in Asian region.

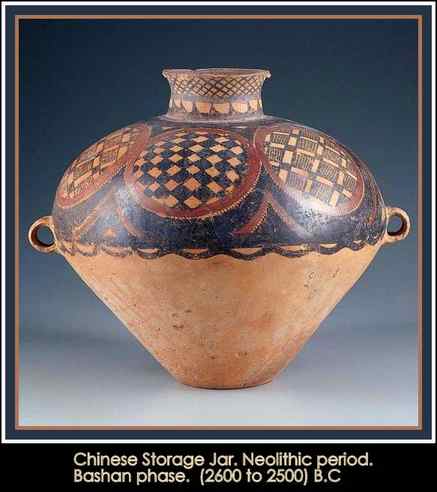

So far the history of Chinese civilization has been situated in the Valley of Yellow River in China; between approximately 5,000 to 4,000 BC in the ” Early Neolithic period “. New archaeological findings at Sanxingdui, a small village about 20 miles northeast of Chengdu in Sichuan province have uncovered objects dating from around 1200 B.C. There were two sacrificial pits containing hundreds of foreign objects never before found buried and hidden for 3,000 years,. Among them objects of gold, imposing human heads made in bronze, bronze with unusual shape masks, as well as some tools of stone and jade, showing how these early men already have certain skills that allows them to represent the elements that make up their daily lives such as viticulture, hunting and fishing. There are aspects of social coexistence represented with themes such as banquets and acrobatic shows, as well as its incipient world of mythology and religion. Today the Chinese people are learning much more about their own culture thanks to the multidisciplinary studies that are underway in this vast country in Asian region.  The agricultural villages in the Valley of the Yellow River tamed animals, made pots for storing grains and liquids and also produced bronze vessels and effective weapons. People who settled in homes along other rivers like the Yangtze and the Huai developed similarly their life. Artistic objects found in these ancient civilizations of China’s approximately 4,000 BC placed them as one of the cultures most skilled in the creation of beautiful and practical objects. The early history of China is traditionally divided into three dynasties: – Hsia or Xia (2205-1766 B.C.). – Shang (1766-1050 B.C.). – Zhou (1050-256 B.C.). As I had mentioned before;Chinese culture since ancient times has always been closely identified with nature, in which the rivers and Mountains occupy the center of their attention. Nature was widely represented in their paintings and ceramics decorations, even the buildings were made with shapes that resemble the mountains. Those buildings are focused on the practical use not in its decoration. Chinese architect and craftsmen from ancient times combined the architectural features of the building with its surrounding and integrate them perfectly balanced with nature. The Great Wall of China a renowned architectural wonder made to protect the country along miles and miles was at the top of mountains, taking advantage of a natural geography of a protruding landscape. They made gardens with gentle and simple designs with the intention to represent a perfect microcosm where water, plants, flowers and animals are perfectly combined. With this representation of natural elements, the Chinese people wanted to get a balanced integration between man and nature. During the Buddhist and Taoist period this respect, veneration and protection of nature rich a peaks and can be perceived very well in its representations of art in the caves, sanctuaries and decorated objects of everyday life that have been conserved.

The agricultural villages in the Valley of the Yellow River tamed animals, made pots for storing grains and liquids and also produced bronze vessels and effective weapons. People who settled in homes along other rivers like the Yangtze and the Huai developed similarly their life. Artistic objects found in these ancient civilizations of China’s approximately 4,000 BC placed them as one of the cultures most skilled in the creation of beautiful and practical objects. The early history of China is traditionally divided into three dynasties: – Hsia or Xia (2205-1766 B.C.). – Shang (1766-1050 B.C.). – Zhou (1050-256 B.C.). As I had mentioned before;Chinese culture since ancient times has always been closely identified with nature, in which the rivers and Mountains occupy the center of their attention. Nature was widely represented in their paintings and ceramics decorations, even the buildings were made with shapes that resemble the mountains. Those buildings are focused on the practical use not in its decoration. Chinese architect and craftsmen from ancient times combined the architectural features of the building with its surrounding and integrate them perfectly balanced with nature. The Great Wall of China a renowned architectural wonder made to protect the country along miles and miles was at the top of mountains, taking advantage of a natural geography of a protruding landscape. They made gardens with gentle and simple designs with the intention to represent a perfect microcosm where water, plants, flowers and animals are perfectly combined. With this representation of natural elements, the Chinese people wanted to get a balanced integration between man and nature. During the Buddhist and Taoist period this respect, veneration and protection of nature rich a peaks and can be perceived very well in its representations of art in the caves, sanctuaries and decorated objects of everyday life that have been conserved.  Thematics of artistic expressions, including stories and poems, mainly revolved around nature, rivers, mountains and valleys where mythological creatures with super powers influenced their lives. It is known that in the Shang dynasty period, they believed in the existence of a good and all-powerful dragon that they believed lived in the seas and rivers, and could rise to the heavens. They do not directly worship the gods in ancient times; they demanded justice and favors through their ancestors. Legends and stories told at night in discussions around campfires must have helped spur the social and cultural evolution of these first humans, who poured their imagination in to decoration of objects, such as pottery, paintings and weapons. Their imagination was later reflected in their writings symbols and thanks to this the legends and important historical events have come to us.

Thematics of artistic expressions, including stories and poems, mainly revolved around nature, rivers, mountains and valleys where mythological creatures with super powers influenced their lives. It is known that in the Shang dynasty period, they believed in the existence of a good and all-powerful dragon that they believed lived in the seas and rivers, and could rise to the heavens. They do not directly worship the gods in ancient times; they demanded justice and favors through their ancestors. Legends and stories told at night in discussions around campfires must have helped spur the social and cultural evolution of these first humans, who poured their imagination in to decoration of objects, such as pottery, paintings and weapons. Their imagination was later reflected in their writings symbols and thanks to this the legends and important historical events have come to us.

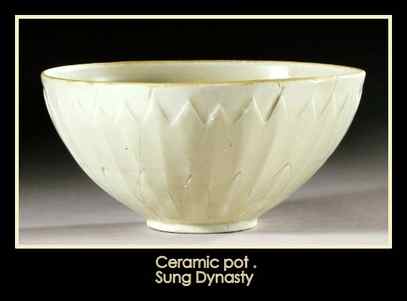

In early times the Chinese paintings were made using a lot of colors and artistically located in them was their calligraphy, once this one was invented, to the point that it prevails over the images represented throughout its history in some stages. The calligraphy of China raise the level of their artistic decorations and was perfectly integrated into their pictorial representations, on the embossment of practical bronze vessels, as well as in the grip of weapons, in their beautiful lacquered wood objects, in their colorful textiles of exquisite beauty and even in decorative wood elements that were part of its buildings. This form of artistic expression and communication is considering an art that is helping today the better understanding of their plastic works in general and the historical and socio-economic context in which they were created. Skill and expressive quality in the practice of calligraphy and painting helped establish one’s status in a society of learned individuals from the Song dynasty (960–1279) onward. Calligraphy was represented in decorations since the days when they only were pictograms, until they become ideograms artistically representing ideas trough symbols. Their calligraphy was unified by imperial decree throughout China by the first emperor Ying Zheng, so even though they were speaking different dialects across the country could understand each other thanks to the writing symbols. He imposed in the country the use of the zhuanshu style as standard writing system, laying thus the basis for the further evolution of Chinese characters. Calligraphy has also led to the development of many forms of art in China, including carved seals, ornate paperweights, flags or banners and other pieces made of stone. All made with a practical function but in which the decorative aspect was also observe. Their representation of nature although very detailed and colorful in early periods as mentioned earlier, dramatically changed along the way to become a painting style with two tones of colors with different shades, although they continue working with high attention to details. This change is related to the school of painting creation by the artist and patron, Emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty in the 12th century, which promotes Taoism during his tenure. This is the style of Chinese painting period in which their artistic creations were not based on real scenes, they are more idyllic, yet imaginative and gentle, with very detailed depiction of nature feature, but in which the human figure is no more than a tiny element represented in beautiful and romantic landscapes and integrated seamlessly in it. The calligraphy gets from this point on an important role in the painting.

The Ancient Chinese people art and their religious belief representation.

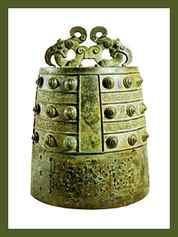

For the ancient Chinese was always very important show respect to their ancestors, probably to the same level as other cultures worshipped their gods. They performed the Oracle divination by reading the bones. Remains of those pertaining to the Shang dynasty have been found in which can be perceive they valued bronze material more than gold. On the bronze vessels, the Shang King offered wine as a tribute to their gods and honored their ancestors. The bronze also was used in domestic tasks developing vessels to contain wine and water, although its high content of lead may had been harmful to their health. Religion was associated with the cosmology in ancient Chinese culture, the movements of the planets and stars were represented in Shang dynasty (1766-1050 B.C.); showing their acute observation capacity and proverbial patience when they use this knowledge to their advantage in agriculture. They represented in art this knowledge, leaving proof of this in pottery with decorations of stars and Zodiac symbols.

Inventions attributed to Chinese civilization related to art.

Many are the inventions attributed to the Chinese people in ancient times that are directly related to their art, and those are the one about to talk in this article. They were known for keep the secrets of their skills in each trade well protected for millenniums in with no foreigner could obtain them. Many inventions related to the art in China were invented hundreds and even thousands of years before the Western civilizations. The invention of a method to print with ink over paper made from rice paste was one of the most significance. Noteworthy was also the elaboration of beautiful ceramics with practical use, but when the porcelain was discovered, were famous for their perfection in its design and detailed decoration. They kept for centuries for themselves the secret of how to do porcelain vessels. For the Chinese, it was not only an economic issue, but also a way to honor family traditions.  Its artisan tradition, with attention to detail and hard work turned their developed objects into exquisite works of art. As soon as the products of this ancient Chinese culture are known in Western civilization have high demand, mainly for its high quality, plus an aura of mysticism about the unknown Eastern civilization that captivated immediately the imagination and desire of upper class in the West to own so wonderful and exotic goods. The secret of making porcelain for example was protected by the Chinese authorities with the death penalty to those who dared to reveal it, even it was forbidden for the foreign dealer visit the interior of China and only in specific commercial places designated near the coast they could obtain the goods. They have always been cautious about the commercialization of their products tending to rather be economically self-sufficient, but they had to adapt to new economic necessities’ to increase its monetary flow due to the growth of the population, creating specific products to export in line to the Western taste.

Its artisan tradition, with attention to detail and hard work turned their developed objects into exquisite works of art. As soon as the products of this ancient Chinese culture are known in Western civilization have high demand, mainly for its high quality, plus an aura of mysticism about the unknown Eastern civilization that captivated immediately the imagination and desire of upper class in the West to own so wonderful and exotic goods. The secret of making porcelain for example was protected by the Chinese authorities with the death penalty to those who dared to reveal it, even it was forbidden for the foreign dealer visit the interior of China and only in specific commercial places designated near the coast they could obtain the goods. They have always been cautious about the commercialization of their products tending to rather be economically self-sufficient, but they had to adapt to new economic necessities’ to increase its monetary flow due to the growth of the population, creating specific products to export in line to the Western taste.  Equally protected was the method for the production of silk fabrics which was discovered in China 5000 years ago. The famous Silk Road was developed by Western countries to obtain coveted merchandise, its soft and light texture reached high appreciation and demand that were compared with the value of gold and even magical attributes were also conferred to the silk. It is well known that the Roman Empire citizens did care so much for this fabulous fabric and imported such huge amount that textiles trade protection laws was decreed by the Roman authorities. Chinese were masters in the use of wood for construction, furniture and artistic decorations. In China the elaboration of various wooden objects becomes also a trade which passes from father to son for generations; as other trades did. Bamboo and precious wood objects were developed for centuries by them with practical use and detailed decoration, some with very difficult intricate designs, among them hand fans, jewelers boxes, containers for incense, as well as diverse architectural elements such as doors and windows in which not a single nail is used, but putting instead overlapping wood pieces with a pretty clever technique that has tested for centuries the efficiency of their innovative constructive skills using wood.

Equally protected was the method for the production of silk fabrics which was discovered in China 5000 years ago. The famous Silk Road was developed by Western countries to obtain coveted merchandise, its soft and light texture reached high appreciation and demand that were compared with the value of gold and even magical attributes were also conferred to the silk. It is well known that the Roman Empire citizens did care so much for this fabulous fabric and imported such huge amount that textiles trade protection laws was decreed by the Roman authorities. Chinese were masters in the use of wood for construction, furniture and artistic decorations. In China the elaboration of various wooden objects becomes also a trade which passes from father to son for generations; as other trades did. Bamboo and precious wood objects were developed for centuries by them with practical use and detailed decoration, some with very difficult intricate designs, among them hand fans, jewelers boxes, containers for incense, as well as diverse architectural elements such as doors and windows in which not a single nail is used, but putting instead overlapping wood pieces with a pretty clever technique that has tested for centuries the efficiency of their innovative constructive skills using wood.  In Chinese art is often used lacquer; a clear layer of the SAP of the trees used to add beauty and luster to objects made of wood which protects them from insects and the deterioration of climate. The western culture try to imitate in different ways the incredible finish the Chinese provide to their artistic objects some of which had up to sixteen layers of the lacquer. Lot of time, try and error efforts had to be endure by the western artisan’s until they found some decent approach using different techniques that offered a look alike lacked itch effect in their pieces. Although they had certain demand were very expensive due to the hard work and time consuming task that their technique require.

In Chinese art is often used lacquer; a clear layer of the SAP of the trees used to add beauty and luster to objects made of wood which protects them from insects and the deterioration of climate. The western culture try to imitate in different ways the incredible finish the Chinese provide to their artistic objects some of which had up to sixteen layers of the lacquer. Lot of time, try and error efforts had to be endure by the western artisan’s until they found some decent approach using different techniques that offered a look alike lacked itch effect in their pieces. Although they had certain demand were very expensive due to the hard work and time consuming task that their technique require.

The ancient Chinese Folding Screens.

Highlighted among the furniture produced by the Chinese art are the folding screens. The Chinese people have known them as ‘pingfeng’ meaning in Chinese language “to protect from the wind”. It is known the existence of these panels or folding screens from the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD).This screens were very popular through the years and found in palaces and mansions of kingship both in China and European courts, where they used them to divide rooms and for privacy. These folding wooden lacquered panels are combined often with paintings on paper and are true masterpieces showing the screens mostly secular content where dragons, birds, colorful peacocks and landscapes support the illustration of Chinese boundless imagination. There are a variety of types of screen, to be the principal which have vertical and folding screens, although very few of the older ones are preserved. They have been used extensively throughout history and were made as well in other countries over time, following the traditional Chinese mode.  Their amazing ability to create beautiful carved ivory objects is also proverbial. These objects have a wide range of different use with elaborate designs that show scenes of hunting, military confrontations and the courtly life. This illustrations help us to understand the life of these ancient men, their philosophy of life, love for nature and its conflicts as a society.

Their amazing ability to create beautiful carved ivory objects is also proverbial. These objects have a wide range of different use with elaborate designs that show scenes of hunting, military confrontations and the courtly life. This illustrations help us to understand the life of these ancient men, their philosophy of life, love for nature and its conflicts as a society.  Development of carved jade figurines is another artistic manifestation where Chinese artisans shine since ancient times. This material was also used in jewels, boxes and formidable decorative containers intended for religious purposes, many have secular content and practical use and is truly remarkable the quality and beauty reached because this material is very hard and difficult to carve.

Development of carved jade figurines is another artistic manifestation where Chinese artisans shine since ancient times. This material was also used in jewels, boxes and formidable decorative containers intended for religious purposes, many have secular content and practical use and is truly remarkable the quality and beauty reached because this material is very hard and difficult to carve.  The aesthetics of line in calligraphy and painting have had a significant influence on the other arts in China. There are many artistic manifestations in which Chinese ancient culture excel, among them its painting really protrude, with the distinctive way to represent nature perfectly balanced with human life and using calligraphy in them, as well as by combining delicate and poetic typical expression of popular Chinese traditions and legends in their work with clever technique and inventions and applying them to painting, architecture, sculpture, pottery and textiles. This was possible thanks to the imagination and hard work of the unknown craftsmen first and to more intellectually developed artists latter since the creation of the school of painting that produced true masterpieces, many of which have been preserved despite the effects of wars, weather, and religious clashes.

The aesthetics of line in calligraphy and painting have had a significant influence on the other arts in China. There are many artistic manifestations in which Chinese ancient culture excel, among them its painting really protrude, with the distinctive way to represent nature perfectly balanced with human life and using calligraphy in them, as well as by combining delicate and poetic typical expression of popular Chinese traditions and legends in their work with clever technique and inventions and applying them to painting, architecture, sculpture, pottery and textiles. This was possible thanks to the imagination and hard work of the unknown craftsmen first and to more intellectually developed artists latter since the creation of the school of painting that produced true masterpieces, many of which have been preserved despite the effects of wars, weather, and religious clashes.