[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”VGSN,”]

Van Gogh’s Night Visions

With his bright sunflowers, searing wheat fields and blazing yellow skies, Vincent van Gogh was fanatic about light. “Oh! that beautiful midsummer sun here,” he wrote to the painter Émile Bernard in 1888 from the south of France. “It beats down on one’s head, and I haven’t the slightest doubt that it makes one crazy. But as I was so to begin with, I only enjoy it.”

Van Gogh was also enthralled with night, as he wrote to his brother Theo that same year: “It often seems to me that the night is much more alive and richly colored than the day. The problem of painting night scenes and effects on the spot and actually by night interests me enormously.”

What van Gogh fixed on, by daylight or at night, gave the world many of its most treasured paintings. His 1888 Sunflowers, says critic Robert Hughes, “remains much the most popular still life in the history of art, the botanical answer to the Mona Lisa.” And van Gogh’s visionary landscape The Starry Night, done the next year, has long ranked as the most popular painting at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). This inspired the museum, in collaboration with Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, to mount the exhibition “Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night” (through January 5, 2009). It will then travel to the Van Gogh Museum (February 13-June 7, 2009).

“The van Gogh we usually think of, that painter of the most audacious, crazy, passionate, frenzied, unleashed bursts of brushwork, may be more evident in his daylight paintings,” says MoMA’s curator for the show, Joachim Pissarro, great-grandson of the French Impressionist Camille Pissarro. “But in paintings such as the Arles café at night, his touch is more restrained and you really see his intelligence at work. Despite all the mental anguish and depression he experienced, van Gogh never ceased to enjoy an astonishingly clear self-awareness and consciousness of what he was doing.”

In an essay for the exhibition catalog, Pissarro tries to clear up some popular mythology: “Contrary to an enduring misconception of van Gogh as a rough and ready chromomaniac driven by his instincts to render what he saw almost as quickly as he saw it, the artist’s twilight and night scenes are actually elaborate constructions that also call on his vast literary knowledge.” Van Gogh himself hinted at this in a letter to his sister Wil, written in 1888 as he was painting his first starry night canvas. He was inspired, he said, by imagery in the poems by Walt Whitman he was reading: “He sees. under the great starlit vault of heaven a something which after all one can only call God—and eternity in its place above the world.”

It seems that van Gogh never dreamed his paintings would become such fixed stars in the art firmament. In 1890, less than two months before he ended his life with a pistol shot, he wrote to a Paris newspaper critic who had praised his work, “It is absolutely certain that I shall never do important things.” He was then 37 years old, had been painting for less than ten years and had sold next to nothing. In his last letter to Theo, found on the artist at his death, he had written: “Well, my own work, I am risking my life for it, and my reason has half foundered because of it.”

Like his paintings, van Gogh’s biography has gone into legend. He was born in 1853 in the Netherlands; his father was a minister, his uncles, successful art dealers. He was dismissed while working as a missionary in southwest Belgium for being too zealous and failed as an art salesman by being too honest. When he took up drawing and painting, his originality offended his teachers. One student later described the scene at the Antwerp Academy where van Gogh enrolled: “On that day the pupils had to paint two wrestlers, who were posed on the platform, stripped to the waist. Van Gogh started painting feverishly, furiously, with a rapidity that stupefied his fellow students. He laid on his paint so thickly that his colors literally dripped from his canvas on to the floor.” He was promptly kicked out of the class.

But alone in a studio or in the fields, van Gogh’s discipline was as firm as his genius was unruly, and he taught himself all the elements of classical technique with painstaking thoroughness. He copied and recopied lessons from a standard academic treatise on drawing until he could draw like the old masters, before letting his own vision loose in paint. Although he knew he needed the utmost technical skill, he confessed to an artist friend that he aimed to paint with such “expressive force” that people would say, “I have no technique.”

By the early 1880s, Theo, who was four years younger than Vincent, was finding success as a Paris art dealer and had begun supporting his brother with a monthly stipend. Vincent sent Theo his astonishing canvases, but Theo couldn’t sell them. In the spring of 1889 after receiving a shipment of paintings that included the now-famous Sunflowers, the younger brother tried to reassure the elder: “When we see that the Pissarros, the Gauguins, the Renoirs, the Guillaumins do not sell, one ought to be almost glad of not having the public’s favor, seeing that those who have it now will not have it forever, and it is quite possible that times will change very shortly.” But time was running out.

Growing up in the Brabant, the southern region of the Netherlands, Vincent had absorbed the dark palette of great Dutch painters such as Frans Hals and Rembrandt. As an art student in Antwerp, he had the opportunity to visit museums, see the work of his contemporaries and frequent cafés and performances. In March 1886, he went to join Theo in Paris. There, having encountered young painters like Toulouse-Lautrec, Gauguin and Signac, as well as older artists such as Pissarro, Degas and Monet, he adopted the brighter colors of modern art. But with his move to Arles, in the south of France, in February 1888, the expressive force he’d been searching for at last erupted. Alone in the sun-drenched fields and gaslit night cafés of Arles, he found his own palette of bright yellows and somber blues, gay geranium oranges and soft lilacs. His skies became yellow, pink and green, with violet stripes. He painted feverishly, “quick as lightning,” he boasted. And then, just as he achieved a new mastery over brush and pigment, he lost control of his life. In a fit of hallucinations and anguish in December 1888, he severed part of his ear and delivered it to a prostitute at a local brothel.

Gauguin, who had come to Arles to paint with him, fled to Paris, and van Gogh, after his neighbors petitioned the police, was locked up in a hospital. From then on, the fits recurred unpredictably, and he spent most of the last two years of his life in asylums, first in Arles and then in Saint-Rémy, painting what he could see through the bars of his window or from the surrounding gardens and fields. “Life passes like this,” he wrote to Theo from Saint-Rémy in September 1889, “time does not return, but I am dead set on my work, for just this very reason, that I know the opportunities of working do not return. Especially in my case, in which a more violent attack may forever destroy my power to paint.”

When the attacks seemed to subside in May 1890, van Gogh left Saint-Rémy for Auvers-sur-Oise, a small village near Paris where Dr. Paul Gachet, a local physician and friend to many painters, agreed to care for him. But van Gogh’s paintings proved more successful than the doctor’s treatments. Among the artist’s last efforts was the tumultuous Wheatfield with Crows, in which dark and light, near and far, joy and anguish, all seem bound together in a frenzy of paint that can only be called apocalyptic. Van Gogh shot himself soon after painting it and died two days later. He was buried in a graveyard next to the field.

Theo had been at Vincent’s side as the artist died and, according to Bernard, left the graveyard at Auvers “broken by grief.” He never recovered. He barely had time to present a show of Vincent’s paintings in his Paris apartment. Six months later he, too, died—out of his mind and incoherent in a clinic in Holland, where he had been taken by his wife because of his increasingly violent outbursts. (One theory holds that both Theo and Vincent, and probably their sister Wil, all suffered from an inherited metabolic disorder that caused their similar physical and mental symptoms.) He now lies buried next to his brother in Auvers.

Against the backdrop of this poignant biography, the new exhibition of van Gogh’s night pictures at MoMA takes on added significance. For it was to the night sky, and to the stars, that van Gogh often looked for solace. The problems of painting night scenes on the spot held more than a technical interest and challenge for him. When he looked at the night sky, he wrote to Theo in August 1888, he saw “the mysterious brightness of a pale star in the infinite.” When you are well, he went on, “you must be able to live on a piece of bread while you are working all day, and have enough strength to smoke and drink your glass in the evening. And all the same to feel the stars and the infinite high and clear above you. Then life is almost enchanted after all.”

Van Gogh saw the night as a period of reflection and meditation after a day of activity, says MoMA curatorial assistant Jennifer Field, one of the organizers of the exhibition. “It was also this kind of metaphor for the cycle of life. And he linked this with the changing of the seasons.”

In Arles, in 1888 and 1889, van Gogh’s paintings took on a mystical, dreamlike quality. Straight lines became wavy, colors intensified, thick paint became thicker, sometimes squeezed straight onto the canvas from the tube. Some of these changes were later taken as a sign of his madness, and even van Gogh feared that “some of my pictures certainly show traces of having been painted by a sick man.” But there was premeditation and technique behind these distortions, as he tried to put a sense of life’s mysteries into paint. In a letter to Wil, he explained that “the bizarre lines, purposely selected and multiplied, meandering all through the picture, may fail to give the garden a vulgar resemblance, but may present it to our minds as seen in a dream, depicting its character, and at the same time stranger than it is in reality.”

The artist’s focus on the relationship between dreams and reality—and life and death—had a profound meaning for him, as he had confided to Theo in a letter a year before his first crisis in Arles. “Looking at the stars always makes me dream, as simply as I dream over the black dots representing towns and villages on a map. Why, I ask myself, shouldn’t the shining dots of the sky be as accessible as the black dots on the map of France? Just as we take the train to get to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to reach a star.”

His interest in mixing dreams and reality, observation and imagination, is particularly evident in the night paintings he made in Arles and Saint-Rémy in 1889 and 1890, in which he not only conquered the difficulties of using color to depict darkness but also went a long way toward capturing the spiritual and symbolic meanings that he saw in the night.

“He lived at night,” says Pissarro. “He didn’t sleep until three or four in the morning. He wrote, read, drank, went to see friends, spent entire nights in cafés . or meditated over the very rich associations that he saw in the night. It was during the night hours that his experiments with imagination and memory went the farthest.”

Van Gogh told Theo that in depicting the interior of a night café, where he had slept among the night prowlers of Arles, “I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green.” He stayed up three consecutive nights to paint the “rotten joint,” he said. “Everywhere there is a clash and contrast of the most disparate reds and greens in the figures of little sleeping hooligans, in the empty, dreary room. the blood-red and the yellow-green of the billiard table.”

Van Gogh considered it one of the ugliest paintings he’d made, but also one of the most “real.” His first painting of the starry sky, The Starry Night over the Rhône (1888), was another exercise in contrasting complementary colors (pairs chosen to heighten each other’s impact). This time, the effect of the painting, with its greenish blue sky, violet-hued town and yellow gaslight, was more romantic. He wrote Wil that he had painted it “at night under a gas jet.”

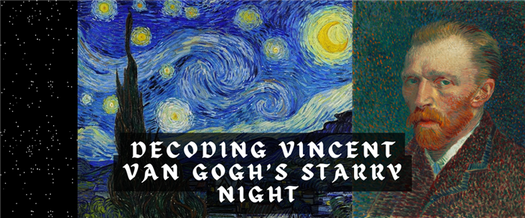

Van Gogh considered his now-iconic The Starry Night, which he painted from his barred window at Saint-Rémy, a failed attempt at abstraction. Before leaving Saint-Rémy, he wrote to Émile Bernard: “I have been slaving away on nature the whole year, hardly thinking of impressionism or of this, that and the other. And yet, once again I let myself go reaching for stars that are too big—a new failure—and I have had enough of it.”

Theo liked the painting but was worried. He wrote Vincent that “the expression of your thoughts on nature and living creatures shows how strongly you are attached to them. But how your brain must have labored, and how you have risked everything. ” Vincent didn’t live to know that in his reaching for the stars, he had created a masterpiece.

New Mexico-based painter and printmaker Paul Trachtman wrote about new figurative painters in the October 2007 issue.

Technical challenges

Van Gogh had had the subject of a blue night sky dotted with yellow stars in mind for many months before he painted The Starry Night in late June or early July of 1889. It presented a few technical challenges he wished to confront—namely the use of contrasting color and the complications of painting en plein air (outdoors) at night—and he referenced it repeatedly in letters to family and friends as a promising if problematic theme. “A starry sky, for example, well – it’s a thing that I’d like to try to do,” Van Gogh confessed to the painter Emile Bernard in the spring of 1888, “but how to arrive at that unless I decide to work at home and from the imagination?” (596, 12 April 1888).

As an artist devoted to working whenever possible from prints and illustrations or outside in front of the landscape he was depicting, the idea of painting an invented scene from imagination troubled Van Gogh. When he did paint a first example of the full night sky in Starry Night over the Rhône (1888, oil on canvas, 72.5 x 92 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), an image of the French city of Arles at night, the work was completed outdoors with the help of gas lamplight, but evidence suggests that his second Starry Night was created largely if not exclusively in the studio.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Location

Following the dramatic end to his short-lived collaboration with the painter Paul Gauguin in Arles in 1888 and the infamous breakdown during which he mutilated part of his own ear, Van Gogh was ultimately hospitalized at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, an asylum and clinic for the mentally ill near the village of Saint-Rémy. During his convalescence there, Van Gogh was encouraged to paint, though he rarely ventured more than a few hundred yards from the asylum’s walls.

Saint-Paul-de-Mausole near Saint-Rémy, France (photo: Emdee, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Church (detail), Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm. (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Besides his private room, from which he had a sweeping view of the mountain range of the Alpilles, he was also given a small studio for painting. Since this room did not look out upon the mountains but rather had a view of the asylum’s garden, it is assumed that Van Gogh composed The Starry Night using elements of a few previously completed works still stored in his studio, as well as aspects from imagination and memory. It has even been argued that the church’s spire in the village is somehow more Dutch in character and must have been painted as an amalgamation of several different church spires that van Gogh had depicted years earlier while living in the Netherlands.

Van Gogh also understood the painting to be an exercise in deliberate stylization, telling his brother, “These are exaggerations from the point of view of arrangement, their lines are contorted like those of ancient woodcuts” (805, c. 20 September 1889). Similar to his friends Bernard and Gauguin, van Gogh was experimenting with a style inspired in part by medieval woodcuts, with their thick outlines and simplified forms.

Stars (detail), Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The colors of the night sky

On the other hand, The Starry Night evidences Van Gogh’s extended observation of the night sky. After leaving Paris for more rural areas in southern France, Van Gogh was able to spend hours contemplating the stars without interference from gas or electric city street lights, which were increasingly in use by the late nineteenth century. “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big” 777, c. 31 May – 6 June 1889). As he wrote to his sister Willemien van Gogh from Arles,

It often seems to me that the night is even more richly colored than the day, colored with the most intense violets, blues and greens. If you look carefully, you’ll see that some stars are lemony, others have a pink, green, forget-me-not blue glow. And without laboring the point, it’s clear to paint a starry sky it’s not nearly enough to put white spots on blue-black. (678, 14 September 1888)

Van Gogh followed his own advice, and his canvas demonstrates the wide variety of colors he perceived on clear nights.

Painting by night

The Museum of Modern Art, New York Until 5 January 2009 and then at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, from 13 February to 7 June 2009.

Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night, an exquisite exhibition now on show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, explores this artist’s fascination with portraying the night. Unlike earlier artists who painted night scenes by day from memory, Vincent van Gogh painted his nocturnal scenes on the spot, using gaslight and colour in innovative ways to depict sunset and starlight in luminous yellow tones. As the exhibition’s curator Joachim Pissarro explains, van Gogh was the first artist “to blend together gaslight — artificial, urban light — with starry light in a painting”. Both lights blaze with “the same kind of buzzing, bursting of energy, a kind of weird kinship”.

Credit: H. LEWANDOWSKI/RÉUNION DES MUSÉES NATIONAUX/ART RESOURCE

That “weird kinship” is captured perfectly in van Gogh’s 1888 work The Starry Night Over the Rhône (pictured), his first attempt to paint the stars. The Great Bear constellation burns green in the sky, while across the river, the distant orange gas lamps of the French town of Arles are reflected in the water like the stars’ earthly companions. Gas lamps gleam with the same fierce energy in The Night Café, a sparsely occupied saloon that van Gogh painted during three sleepless nights in 1888. The glare of the four gas lamps hanging from the ceiling combines with the painting’s high-pitched palette of greens and reds — six or seven shades from “blood-red to delicate pink” — to evoke, as the artist wrote, “the terrible human passions”. The melancholy of this scene contrasts sharply with the joyful hubbub of The Dance Hall in Arles (1888), exhibited here beside The Night Café for the first time; the golden orbs of the gas lamps bathe the dancers in a warm and vibrant light.

These bright, spirited scenes seem eons away from van Gogh’s earlier, muddy-dark depictions of country cottages and peasants. In his first significant interior night scene, The Potato Eaters, painted in 1885, a single oil lamp casts a pallid glow over the rough faces of the farmers as they share their meagre meal. In The Cottage, painted the same year, a narrow gash of sunset sky and the smudge of an oily flame in a window are all that animate the green-black evening shadows. The light of oil lamps may also be glimpsed inside the houses of The Starry Night, the exhibition’s most magnificent work. Van Gogh painted it in June 1889 — a year before his suicide — while confined in an asylum at Saint-Rémy in the south of France. In this delirious vista, clouds churn, the crescent Moon shines like a roiling Sun, and tall cypress trees tower in the foreground as symbols of death and the afterlife. Beneath them, the houses of the village stand serenely, their windows squares of comforting yellow light — beacons of the life inside.