- https://blog.prepscholar.com/what-colors-make-purple

- https://www.artsandcollections.com/a-history-of-the-colour-purple/

- https://kidadl.com/facts/what-color-does-blue-and-purple-make-colorful-facts-for-kids

- https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/mar/12/the-invention-of-the-colour-purple

How Do You Get The Color Purple?

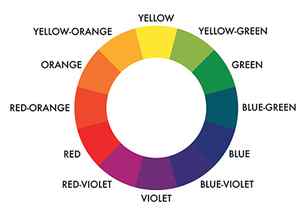

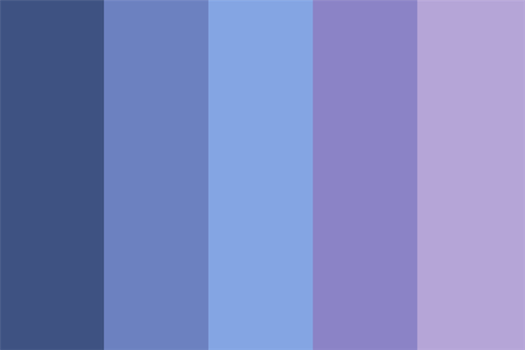

Blue and red are essential to creating purple, but you can mix in other colors to create different shades of purple shades of purple In common English usage, purple is a range of hues of color occurring between red and blue. However, the meaning of the term purple is not well defined. There is confusion about the meaning of the terms purple and violet even among native speakers of English. https://en.wikipedia.org › wiki › Shades_of_purple

Table of Contents

Shades of purple – Wikipedia

. Adding white, yellow, or gray to your mixture of blue and red will give you a lighter purple.

Purple is relatively rare in nature, and the exotic colour has accordingly been considered sacred. The word actually derives from the name of the Tyrian purple dye manufactured from mucus secreted by the spiny dye-murex snail. The dye came from the Phoenician trading city of Tyre, now in modern-day Lebanon.

Generally Is purple made from blue? Let us go through the simple answer of how these two colors blend in with other colors. Blue mixed with the primary color yellow makes the color green, which is a secondary color. Blue when mixed with the other primary color red creates the color purple, which is a secondary color.

Here You Can Watch The Video What Colors Make Purple? The Ultimate Guide to Mixing Purple

Is purple made from snail snot?

Because of this, purple was used to denote wealth and power. Tyrian purple was made from the mucous of sea snails – or muricidae, more commonly called murex – and an incredible amount was needed to yield just a tiny amount of dye.

Is the color purple a real color?

The colour purple does not exist in the real world. Apparently it’s true. A rainbow of light from red to violet floods our surroundings, but there is no such thing as purple light. Purple only exists in our heads.

What is the true meaning of the color purple?

The color purple is often associated with royalty, nobility, luxury, power, and ambition. Purple also represents meanings of wealth, extravagance, creativity, wisdom, dignity, grandeur, devotion, peace, pride, mystery, independence, and magic.

Why did purple become the color of royalty?

Purple’s elite status stems from the rarity and cost of the dye originally used to produce it. Purple fabric used to be so outrageously expensive that only rulers could afford it. The dye initially used to make purple came from the Phoenician trading city of Tyre, which is now in modern-day Lebanon.

What do purple mean in the Bible?

wealth, prosperity The Bible also reveals purple to be symbolic of wealth, prosperity, and luxury (Exodus 28:5, Ezekiel 27:7 . The ephod was made of gold, of blue, and purple, of scarlet, and fined twined linen, with cunning work. Gold is the bible color associated with the subject of kings and kingdoms.

Who invented the purple dye?

William Henry Perkin, a young London chemist, patented a synthesis in 1856 for a purple dye he created by accident whilst trying to synthesise quinine, a Victorian anti-malarial. This discovery brought purple, a colour so expensive it had previously only been afforded by royalty and the church, to the mass-market.

Why did purple become the color of royalty?

Purple’s elite status stems from the rarity and cost of the dye originally used to produce it. Purple fabric used to be so outrageously expensive that only rulers could afford it. The dye initially used to make purple came from the Phoenician trading city of Tyre, which is now in modern-day Lebanon.

What do purple mean in the Bible?

wealth, prosperity The Bible also reveals purple to be symbolic of wealth, prosperity, and luxury (Exodus 28:5, Ezekiel 27:7 . The ephod was made of gold, of blue, and purple, of scarlet, and fined twined linen, with cunning work. Gold is the bible color associated with the subject of kings and kingdoms.

Who invented the purple dye?

William Henry Perkin, a young London chemist, patented a synthesis in 1856 for a purple dye he created by accident whilst trying to synthesise quinine, a Victorian anti-malarial. This discovery brought purple, a colour so expensive it had previously only been afforded by royalty and the church, to the mass-market.

Why did purple become the color of royalty?

Purple’s elite status stems from the rarity and cost of the dye originally used to produce it. Purple fabric used to be so outrageously expensive that only rulers could afford it. The dye initially used to make purple came from the Phoenician trading city of Tyre, which is now in modern-day Lebanon.

What do purple mean in the Bible?

wealth, prosperity The Bible also reveals purple to be symbolic of wealth, prosperity, and luxury (Exodus 28:5, Ezekiel 27:7 . The ephod was made of gold, of blue, and purple, of scarlet, and fined twined linen, with cunning work. Gold is the bible color associated with the subject of kings and kingdoms.

Who invented the purple dye?

William Henry Perkin, a young London chemist, patented a synthesis in 1856 for a purple dye he created by accident whilst trying to synthesise quinine, a Victorian anti-malarial. This discovery brought purple, a colour so expensive it had previously only been afforded by royalty and the church, to the mass-market.

Tyrian Purple: The disgusting origins of the colour purple

Created from the desiccated glands of sea snails, the colour purple has nevertheless come to define royalty. Kelly Grovier looks at how the hue shook off its unexpected source.

Purple is a paradox, a contradiction of a colour. Associated since antiquity with regality, luxuriance, and the loftiness of intellectual and spiritual ideals, purple was, for many millennia, chiefly distilled from a dehydrated mucous gland of molluscs that lies just behind the rectum: the bottom of the bottom-feeders. That insalubrious process, undertaken since at least the 16th Century BC (and perhaps first in Phoenicia, a name that means, literally, ‘purple land’), was notoriously malodorous and required an impervious sniffer and a strong stomach. Though purple may have symbolised a higher order, it reeked of a lower ordure.

More like this:

It took tens of thousands of desiccated hypobranchial glands, wrenched from the calcified coils of spiny murex sea snails before being dried and boiled, to colour even a single small swatch of fabric, whose fibres, long after staining, retained the stench of the invertebrate’s marine excretions. Unlike other textile colours, whose lustre faded rapidly, Tyrian purple (so-called after the Phoenician city that honed its harvesting) only intensified with weathering and wear – a miraculous quality that commanded an exorbitant price, exceeding the pigment’s weight in precious metals.

In Hercules’ Dog Discovers Purple Dye, Peter Paul Rubens shows the mythological hero patting a hound who has been sniffing around the murex mollusc (Credit: Wikimedia)

So sought after was the colour (which eventually became the only shade in which priests and kings, emperors and magistrates would enrobe themselves), elaborate origin myths emerged to explain the dye’s predestined discovery. According to the 2nd-Century Greek grammarian Julius Pollux, purple was serendipitously stumbled across by the beachcombing dog of the demigod Heracles (the Roman god Hercules), who was on his way to canoodle with a nymph when his four-legged friend paused to gnaw on a sea snail on the seashore.

A portrayal of the scene shows the hunky mythological hero kneeling to pat the head of a hound that has just been chewing a snail’s anus

When the nymph saw the purple-stained muzzle of Heracles’ companion, she requested a garment of the same rich complexion. A portrayal of the scene, depicted around 1636 by the 17th-Century Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, Hercules’ Dog Discovers Purple Dye, shows the hunky mythological hero kneeling to pat the head of a hound that has just been chewing a snail’s anus. Though Rubens’ whimsical oil-on-panel painting erroneously depicts a spiral nautilus shell (rather than a prickly murex one), the work nevertheless corroborates the contention that purple, as a rancid dog’s-dinner of a hue, makes for an incongruous choice as a symbol of enduring majesty and power. This is a colour that pretends to transcend the vulgar vagaries of this world, all the while remaining mired in its muck.

Imperial cloth

In ancient Greece, the right to clad oneself in purgative purple was tightly controlled by legislation. The higher your social and political rank, the more extracted rectal mucus you could swaddle yourself in. According to the Roman historian Suetonius, King Ptolemy of Mauretania’s sartorial decision to cloak himself in purple on a visit to the Emperor Caligula, cost Ptolemy his life. Caligula interpreted the fashion statement as an act of imperial aggression and had his guest killed. Purple, it seems, was also to die for.

Given its invertebrate faecal inception, its putrid stench, and its proximity to the colour of corporeal distress, it is surprising that purple emerged as a symbol of worldly might

That the colour purple should have provoked the spilling of blood is perhaps unsurprising in the bruising light of its own haemoglobin glimmer. The nearer to the shade of clotted human blood that a manufacturer of the dye could manage to condense, the dearer his product. Given its invertebrate faecal inception, its putrid stench, and its proximity to the colour of corporeal distress, it is surprising that purple should ever have emerged as a symbol of worldly might, let alone otherworldly dominion.

Michelangelo’s dramatic fresco The Last Judgment, on the walls of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, shows Christ in a purple robe (Credit: Wikimedia)

It was customary in Old Master depictions of the heavenly host, and of Mary and Christ himself (who is described in the Book of Mark as laden by his tormentors with purple clothes, lampooning his supposed status as ‘King of the Jews’), to transfer the raiments of royal authority to those taking charge of the hereafter. When seen through the lens of the dye’s unsavoury forging, the purple robe that seems forever to be slipping from the suspended physique of Christ in Michelangelo’s dramatic fresco The Last Judgment, which troubles the walls of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, can be understood as another tawdry layer of worldly trappings that the Messiah’s Second Coming overcomes. This is the image of a purified humanity coming out of its compromised shell.

That teasing tension between noxious waste and exalted authority, between what’s visceral and virtuous, arguably seeps deep into the weave of every image that relies on the colour for its narrative power. Is it significant that when Raphael, elsewhere in the Vatican, imagines his famous soirée of ancient philosophers, The School of Athens, that his fresco’s central axis should be comprised of a purple-clad Leonardo da Vinci (in the role of Plato) and, just below him, scribbling on a block of marble, a purple-shirted Michelangelo (playing Heraclitus)? That the figures are, albeit in dress-up, the artist’s two most distinguished contemporaries, only amplifies their importance and companionability. Plato (who points upwards) was of course obsessed with all things endless, elevated, and ideal, while Heraclitus was famously forlorn by his focus on the fleetingness of things. Only the conflicted colour of purple – at once exquisite and excretory – could entwine the opposing dispositions into an equilibrium of eternal tension.

Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens depicts Leonardo da Vinci (in the role of Plato) and Michelangelo (playing Heraclitus) – both in purple (Credit: Wikimedia)

In time, the arduous task of disembowelling sea snails for their secret would give way to a more salubrious synthetic process. When, in 1856, the 18-year old aspiring British chemist William Henry Perkin accidentally discovered, while attempting to find a cure for malaria, an artificial residue that could rival the sheen of Tyrian Purple, he recognised his good fortune and seized it. Eventually settling on ‘mauveine’ (so-called after the Latin term for the mallow flower, Malva, which boasts a similar shade) as the trademarked name for his profitable invention, Perkin ignited a fashion sensation. Suddenly what had been for centuries an elite hue was widely available – demystifying its use.

Francis Bacon’s 1953 Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X replaces the Pope’s red with Tyrian Purple (Credit: Alamy)

That’s not to say Tyrian Purple disappeared entirely from art or that its portrayal by painters suddenly ceased to intrigue or deepen the narratives of their work. When the Irish artist Francis Bacon resolved to reinvent in the 1950s Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X (1650) for a series of unsettling works popularly known as the ‘screaming popes’, he decided to recast the pontiff’s vestments not as scorching scarlet as his Spanish forebear had, but as pulsating purple. The result was as quietly alarming as the mute caterwaul that howls from his subject’s tortured lips.

Putting to one side the anachronism of Bacon’s vision (Pope Paul II had, five centuries earlier, declared that Tyrian Purple should be replaced by red for all official frocks), Bacon’s sizzling nudge towards violent violet is fitting, as if the Pope were undergoing the excruciating disgorgement of millions of molluscs over many millennia. Bacon’s Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X(1953) can be seen as purple’s silent scream into anguished oblivion – the last gasp of a gorgeously appalling colour.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Why is Purple Considered the Color of Royalty?

The original dye was prized because of supply and demand: It came from the mucous of an exceedingly rare sea snail shell.

Updated: August 30, 2023 | Original: July 15, 2015

The color purple’s ties to kings and queens date back to ancient world, where it was prized for its bold hues and often reserved for the upper crust. The Persian king Cyrus adopted a purple tunic as his royal uniform, and some Roman emperors forbid their citizens from wearing purple clothing under penalty of death.

Purple was especially revered in the Byzantine Empire. Its rulers wore flowing purple robes and signed their edicts in purple ink, and their children were described as being “born in the purple.”

Buckingham Palace

The reason for purple’s regal reputation comes down to a simple case of supply and demand. For centuries, the purple dye trade was centered in the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre in modern day Lebanon. The Phoenicians’ “Tyrian purple” came from a species of sea snail now known as Bolinus brandaris, and it was so exceedingly rare that it became worth its weight in gold. To harvest it, dye-makers had to crack open the snail’s shell, extract a purple-producing mucus and expose it to sunlight for a precise amount of time. It took as many as 250,000 mollusks to yield just one ounce of usable dye, but the result was a vibrant and long-lasting shade of purple.

Clothes made from the dye were exorbitantly expensive—a pound of purple wool cost more than most people earned in a year—so they naturally became the calling card of the rich and powerful. It also didn’t hurt that Tyrian purple was said to resemble the color of clotted blood—a shade that supposedly carried divine connotations.

The royal class’ purple monopoly finally waned after the fall of the Byzantine empire in the 15th century, but the color didn’t become more widely available until the 1850s, when the first synthetic dyes hit the market.