The Moon is a source of communion between humankind and nature. It also connects people across borders in its thread of beaming, volatile silver. This atmospheric effect of moonlight has inspired a multitude of artists in media such as illustration, painting, and woodblock printing.

Under the Moonlight: Depictions of the Moon in Art

The moon has encouraged humankind’s curiosity and our need to understand the principles of nature since the dawn of time. But what is the role of the moon in art?

Jan 2, 2022 • By Michaela Simonova , MA Comparative Religions & Museum Guide

Since the dawn of civilization, humankind has looked up at the sky to observe a strange moving object that changes its shape every night. Almost every civilization and religion has incorporated the moon into their beliefs and worldview. The mysterious nature of this cosmic object has continually lit up humanity’s imagination. Depictions of the moon have been present in the background of our history, guiding civilizations through their first steps. Let’s have a closer look at some famous examples of the moon in art.

The Moon in Art: The Observer and the Observed

The moon may have been one of the first objects that was observed and documented in art — however, not in the forms you may imagine. One of the oldest examples of the moon in art was found in South Africa — the Lebombo bone, a small portable object with 29 notches that could be 35,000 years old.

Without additional information, it is difficult to conclude whether these cuts truly represent the days of the moon cycle. Can we really call it art or a depiction of the moon? I believe that to a certain extent, we can. After all, if we imagine ancient hunter-gatherers relying on their observational talent and understanding of nature’s cycles to adapt and survive, it is not difficult to imagine that the Moon played a vital role.

Disc and Crescent: Early Depictions of the Moon in Art

Speculations aside, the first “figural” depiction of the moon in art was found in Europe. This 3600-year-old bronze disc was excavated in Germany, and is known as the Nebra Sky Disc, a flat bronze circle decorated with circular and crescent-shaped gold inlays. It may once have been used for astronomical observations. The crescent is most likely the moon, while the circular shapes might be the Sun or the Moon, as well. Since they are all made from the same metal, it is impossible to tell for sure and we must use our imaginations.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription

Thank you!

The moon in art

How to capture the marvellousness of moonlight? As the photos floating around Twitter testify, it is difficult to do so on a smartphone: it comes out as a pitiful streak, a smear, a sad shadow of its original self.

Thankfully many artists throughout the ages have captured the moon through some wonderful lunar art. Now seems a timely moment to shine a light on lunar art, as this year sees no less than three supermoons – the term ‘supermoon’ refers to ‘perigee’, the moon’s closest point to Earth in its elliptic orbit; indeed, supermoons are also known as ‘perigean’ full moons.

The next full moon on 19th February 2019 will be the most super of all – the moon will be 356,846 kilometres from Earth, which is pretty much as close as it gets. What I love about lunar events such as supermoons is the way they seem to unite people the world over, who step into the night and gaze heavenwards in an attempt to glimpse this marvel.

In lunar art, the moon is depicted in places all over the world, in remote mountains, islands, forests, villages, towns, cities. Some highlights include the nineteenth-century paintings Moon Reflected in a Turtle Pool, Seychelles by Marianne North (above), in which purple hues fill the sky and a moon peeps through a palm tree laden with coconuts, and The South Bay at Night With Full Moon by Walter Linsley Meegan, filled with an eerie green light.

Venice, Moonlight by Christopher Williams brilliantly captures, in burgundy light, the silhouettes of the city’s buildings and boats.

Closer to these shores is Street Scene, Wolverhampton, in which the moon hangs over a deserted night street, and Winter Moonrise, Yorkshire.

In many paintings, the moon is seen set in an anonymous landscape, whilst others zoom in closely so the moon fills the painting.

For example, the eighteenth-century painting Landscape, Moonlight shows the moon in a wide context of bridge, sea, sky.

And the beautiful nineteenth-century River With Moonlight Effect by Karl Adloff and River Landscape by Moonlight by George Henry also see the moon in a landscape: the quality of light the artists managed to depict attests to the true power of painting.

Then there is the simple yet potent Mountain and Moon, in an unnamed place, and the nineteenth-century Moonlight in the Forest by Joséphine Bowes in an unnamed forest.

Meanwhile, Silver Moon shows the moon taking up most of the canvas, as it does in Moon and Clouds by Bet Low.

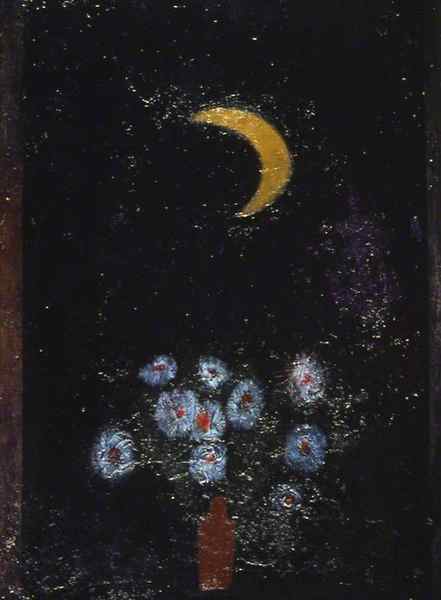

The moon is shown in all of its phases, from gloriously full to a no-less-compelling crescent. A crescent moon hangs in the sky in Landscape, with Crescent Moon, Church and Graveyard and a yellow crescent is also in the more abstract painting Black Night by Robert Leishman.

A Siren in Full Moonlight reminds us of all the extra layers of meaning attached to the full moon, and a full moon is also seen in Moonlight and Lamplight which juxtaposes natural and artificial light.

One of my favourite sayings about the moon is from Anton Chekhov: ‘Don’t tell me the moon is shining, show me the glint of light on broken glass’, and indeed artists have experimented with showing not only the full shine of the moon but in more subtle glints and hints – indeed its elusiveness is spookily shown in The Uncertainty of the Waning Moon by Aguri Kitamura.

There are many paintings powerfully depicting moonlight on the sea, perhaps little wonder given that the moon’s gravitational pull on Earth is the main cause of the rise and fall of ocean tides.

Moonlight, attributed to the nineteenth-century artist Joachim Hierschl-Minerbi, captures just how immensely eerie moonlight can be, here as it reflects on the sea.

The moon’s reflection upon water is also captured in Moonlit Landscape by John Moore of Ipswich, and its journey through the skies in the turquoise-hued Rising Moon, St Ives Bay, Cornwall by Albert Julius Olsson.

A New Moon and a Vortex (The Wave) by Wendy Spooner also strikingly shows this relationship, albeit in a very different, abstract style, and an abstract style is favoured too by Kenneth Lawson in Moon and Sea.

A particularly powerful abstract is also Moon Rising by Denis A. Bowen.

If the moon has a powerful pull on the sea, it has a no less potent effect on us human beings, on our imaginations, minds and emotions.

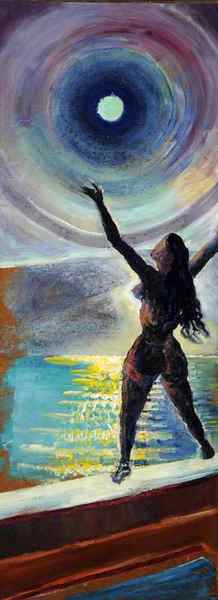

The moon has been a dominant symbol in mythology throughout the ages, taking on all manner of meanings. For a twentieth-century depiction of the emotional pull of the moon see Crying for the Moon by Francis Ferdinand Maurice Cook, which shows a woman with arms outstretched, face held upwards towards the moon.

Moon Dance by Louise Ritchie also captures the mythology of the moon (and brings to mind the eponymous Van Morrison song).

The moon has seeped into our language and expressions and a creative take on this is Once in a Blue Moon by Vanda Harvey, and the painting Over the Moon.

Mankind’s yearning to land on the moon is seen in the cartoonish Baron Munchausen on the Moon and Baron Munchausen Arrives on the Moon by Ray Harryhausen.

I always find the moon when visible in daylight so haunting and this is well shown by Richard Harry Carter in The Rising Moon and Day’s Departure and this painting of Morning attributed to Henry Pether.

Meanwhile, Night by James Arthur O’Connor shows just how much light there is to be found in darkness.

The painting The Moon Goes round the Earth by Keith Henderson shows school children being taught about the movements of the moon and brings to mind memories of first learning about the moon and wondering at it, dreaming about one day walking upon it, or trying to discern the wistful face of the man in the moon.

Delving into artworks in the archive is a reminder that it is never too late to keep learning about all things lunar and appreciating anew the magnificence of the moon.

Anita Sethi, journalist, writer and critic

Share this page

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

Moonlight in art: Turner, Constable, Rubens and Friedrich

Western Masters such as J.M.W. Turner, Peter Paul Rubens, John Constable, and Caspar David Friedrich were more than intrigued – they were mesmerised by moonlight. Their landscapes attempted to hold its never-ending incarnations within the boundaries of materiality, circumscribed in paintings and watercolours of pale blue, green and grey hues.

In the oil on canvas Fishermen at Sea (1796), Turner depicts a small fishing boat struggling against the waves of an open, violent sea. In spite of carrying a flickering lantern, the fishermen are lit by a bright Full Moon, which safeguards them but also reveals the dangers ahead. The painting stresses their vulnerability in relation to nature. In fact, in a broader sense, it emphasises humankind’s subjugation towards the cosmos and its power.

Similarly, in the gouache and watercolour on wove paper Moonlight on River (c. 1826), Turner summons the brevity of moonlight by conveying ‘the physical sensation of light coruscating across the sky and glistening in the water below’ according to Royal Museums Greenwich curator of art Melanie Vandenbrouck. This night-time composition evokes a scenery of transience.

Prior to Turner, in the 17th century Rubens brought Landscape by Moonlight (1635-40) into life. An idyllic view occupies this nocturne: a starry sky, a vivid Moon reflected on a lake, a horse in the shore and green, placid trees in the waterside. The oil on panel pastoral was a response to Flight into Egypt (1609-10), an oil on copper cabinet painting by German artist Adam Elsheimer. In his turn, Rubens was an influence on Constable, suggests Vandenbrouck.

Netley Abbey by Moonlight (c. 1833), a graphite and watercolour on paper by Constable, radiates an other-worldly atmosphere that is intensified by moonlight. Constable and his wife, Maria Bicknell, visited Netley Abbey in 1816. He made a number of pencil studies at the time, but the watercolour was made much later.

In 1828, aged 41, Bicknell died of tuberculosis, leaving behind seven young children. Netley Abbey by Moonlight is hence a sort of visual elegy. The blurry figure in front of a gravestone accentuates the sense of loss, as does the palette dominated by cool blue hues.

A much warmer range of colours was adopted by Caspar David Friedrich in his Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819-20). A well-known painting within German Romanticism, this landscape oil on canvas is the first of a series of three; the other two followed in 1824 and 1825-30. It depicts a couple of friends on a mountain path, seen from behind, gazing at a waxing Moon during nightfall. The composition is yet another example of human communion with nature, inviting the spectator to join the figures in their evening observation.

In a similar fashion, The Lady in Milton’s ‘Comus’ (1784-5 and 1789), by Joseph Wright of Derby, ‘conveys the feelings of the subject represented and in turn affect the emotions of the beholder’, writes Vandenbrouck in the catalogue of The Moon exhibition.

In The Lady in Milton’s ‘Comus’, Wright presents a young woman, ‘Lady’, alone in the woods and lost in the wilderness. She has been separated from her brothers and, fearing the debauched Comus, looks at the Moon in order to plead for safety. While the moonlight could be said to be protecting her, it also increases the tension of the scene, eliciting apprehension and pathos from the viewer.

Beyond Europe: Moonlight in Eastern art

In Japan, the Moon has been a source of inspiration to many artists from as early as the 15th century (such as New Moon over the brushwood gate, an ink on paper from 1405). Names such as Nishimura Shigenaga, Utagawa Yoshitaki, Suzuki Harunobu and Utagawa Hiroshige are amongst these.

In 1789, Ki no Sadamaru collected 72 Kyōka (or parodic) poems related to the satellite and published them in the anthology Ehon kyogetsubo 絵本狂月坊. Kitagawa Utamaro contributed by providing five Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) woodblock prints with the recurring motif of the Full Moon.

No other Japanese artist went as far in contemplation of the Moon, however, as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Between 1885 and 1892, he produced a series of a 100 ukiyo-e, colour woodblock prints called Tsuki hyaku sugata 月百姿 (translated as One Hundred Aspects of the Moon in English).

These illustrations deal with subjects such as folklore, literature, and religion. In fact, they are an ode to the Moon and its phases, since Yoshitoshi used the lunar cycle to represent feelings like introspection, loneliness or sorrow. His images featuring a Full Moon thus hold subtle differences in meaning from the ones showing Waning Gibbous or Waxing Crescent Moons.

The Moon was also a muse to a number of artists based in China, India, and Korea. In China, particularly, the Moon has had a special significance for over a thousand years. The satellite is linked with lunar goddess Chang’e (嫦娥) and her companion Yutu (玉兔), a jade rabbit wielding a mortar and pestle that is constantly pounding her the elixir of life.

Yue Lao ( 月下老人), the god of love and marriage, and Jin Chan (金蟾), a mythical toad, are equally related to the Moon. The depiction of these deities is vital to Chinese iconography, and the portrayal of Chang’e flying to (or over) the Moon has been a constant subject of ink painting since the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

In parallel, Chinese landscape paintings, known as shan shui (山水画, translated as ‘mountain water’ in English), sought to represent the entire cosmos. In this context, moonlight evokes a spiritual connotation, an agency to emphasise inner harmony and tranquillity. In most shan shui, a poem in beautiful calligraphy is included to complement the scenery and explain it. This form of Guóhuà (國畫), as traditional Chinese painting is known today, is strongly informed by Buddhism and Taoism.

From East to West, North to South: the Moon as a connective force

The Moon is much more than a mirror to the Sun. Indeed, it does reflect light, but its gleam has a distinctive and inspiring strength of its own. Long before the advent of electricity, the Moon ruled our night-time activities and, as such, our imaginations.

In painting and printmaking, the allure of the Moon bewitched Baroque, Romantic, Naturalist, Ukiyo-e and Guóhuà artists. The list of painters who employed moonlight in their canvasses is countless, from Vincent Van Gogh (Starry Night, 1889 and White House at Night, 1890) and Henri Rousseau (A Carnival Evening, 1886) to American Modernist Albert Pinkham Ryder (Moonlight Marine, c. 1870-90).

Certainly, as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution, our relationship with the Moon has changed. And yet, the satellite continues to marvel visual artists.

In the midst of a myriad of aesthetical and cultural differences, the Moon remains a connective force. From East to West, its light unifies those living in floodlit cities, tiny fishing villages and remote settlements. As it keeps captivating minds in the 21st century the same way it did in the 1400s or in the 1800s, it will carry on doing so for decades to come.

The Thames and Greenwich Hospital by Moonlight , c. 1854-60, by Henry Pether (1800-80), is a particularly fine example of a nocturne painting owned by Royal Museums Greenwich.

In this oil on canvas, Greenwich Hospital is depicted in the foreground from the west. The architectural details are carefully studied and delineated. The moonlight, reflected from the Thames, illuminates the scene but also creates a ghostly, uncanny atmosphere. The Bellot Memorial Monument, an obelisk unveiled in 1855, can be seen on the right side corner, while the Isle of Dogs lies on the far left. The chimney of the Cumberland Oil Mills, an oil-seed factory that was demolished in the late 1980s, is shown beyond the moored ships.

Pether was the son of English landscape painter Abraham ‘Moonlight’ Pether of Chichester. Like his father, Henry specialised in night-time compositions, adopting the Full Moon as a central motif to his practice. The Thames and Greenwich Hospital by Moonlight is possibly one of his most celebrated pieces.

John Everett (1876-1949) is yet another English painter in our collections who produced a number of night-time compositions. Seascape by moonlight (n.d.) depicts a placid expanse of sea illuminated by the light of a bright Full Moon. Different shades of blue and grey dominate this oil on paper, bequeathed by the artist to the National Maritime Museum in 1949.

The Thames and Greenwich Hospital by Moonlight and Seascape by moonlight is on display at the Queen’s House. Moonlight on River by Turner and Netley Abbey by Moonlight by Constable, as well as The Eighth Month: Moon viewing (1770-5) by Ishikawa Toyomasa; Endymion and Selene (c. 1870) by Victor-Florence Pollet; Harvest Moon (1855) by John Linnell; and Autumn Evening (1994) by Lee Chong-sop all featured in The Moon exhibition.