Personally, I found it easier to do my drawing after dinner when the kids are in bed and the house is fairly quiet.

animation

While every effort has been made to follow citation style rules, there may be some discrepancies. Please refer to the appropriate style manual or other sources if you have any questions.

Select Citation Style

Copy Citation

Share

Share

Share to social media

Give Feedback

External Websites

Feedback

Thank you for your feedback

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

External Websites

- New York Film Academy Student Resources – A Quick History of Animation

- Art Encyclopedia – Animation Art

- Khan Academy – Welcome to Animation!

- Art in Context – 12 Principles of Animation – Learn the Fundamentals of Animation

- World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts – Animation

- University of Toronto – Dynamic Graphics Project – The Fundamental Principles of Animation

Britannica Websites

Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students.

- animation – Children’s Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- animation – Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Print

print Print

Please select which sections you would like to print:

Cite

verifiedCite

While every effort has been made to follow citation style rules, there may be some discrepancies. Please refer to the appropriate style manual or other sources if you have any questions.

Select Citation Style

Copy Citation

Share

Share

Share to social media

Feedback

External Websites

Feedback

Thank you for your feedback

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

External Websites

- New York Film Academy Student Resources – A Quick History of Animation

- Art Encyclopedia – Animation Art

- Khan Academy – Welcome to Animation!

- Art in Context – 12 Principles of Animation – Learn the Fundamentals of Animation

- World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts – Animation

- University of Toronto – Dynamic Graphics Project – The Fundamental Principles of Animation

Britannica Websites

Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students.

- animation – Children’s Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- animation – Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Also known as: cartoon film

Written by

Dave Kehr

Film columnist for The New York Times and former chief film critic for the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News.

Dave Kehr

Fact-checked by

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Encyclopaedia Britannica’s editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge, whether from years of experience gained by working on that content or via study for an advanced degree. They write new content and verify and edit content received from contributors.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Last Updated: Oct 13, 2023 • Article History

Table of Contents

Dumbo

Category: Arts & Culture

Key People: Mary Blair Walt Disney Frank Tashlin Dr. Seuss Miyazaki Hayao . (Show more)

Related Topics: anime computer animation Claymation abstract animation cel animation . (Show more)

Top Questions

What is animation?

Animation is the art of making inanimate objects appear to move. History’s first recorded animator is, arguably, Pygmalion of Greek and Roman mythology. The theory of the animated cartoon preceded the invention of the cinema by half a century.

What place does Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs hold in the history of animation?

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the first film to use up-to-the-minute animation techniques and receive a Hollywood-style release. When it was released in 1937, the film was an immediate box-office sensation and was honoured with a special Academy Award.

Who made the first film-based animation?

The first film-based animation was made by J. Stuart Blackton, whose Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906 launched a successful series of animated films for New York’s pioneering Vitagraph Company.

Who invented rotoscope animation?

The Fleischer brothers invented the rotoscope process, in which a strip of live-action footage can be traced and redrawn as a cartoon. They exploited this technique in their pioneering series Out of the Inkwell (1919–29).

animation, the art of making inanimate objects appear to move. Animation is an artistic impulse that long predates the movies. History’s first recorded animator is Pygmalion of Greek and Roman mythology, a sculptor who created a figure of a woman so perfect that he fell in love with her and begged Venus to bring her to life. Some of the same sense of magic, mystery, and transgression still adheres to contemporary film animation, which has made it a primary vehicle for exploring the overwhelming, often bewildering emotions of childhood—feelings once dealt with by folktales.

Early history

The theory of the animated cartoon preceded the invention of the cinema by half a century. Early experimenters, working to create conversation pieces for Victorian parlours or new sensations for the touring magic-lantern shows, which were a popular form of entertainment, discovered the principle of persistence of vision. If drawings of the stages of an action were shown in fast succession, the human eye would perceive them as a continuous movement. One of the first commercially successful devices, invented by the Belgian Joseph Plateau in 1832, was the phenakistoscope, a spinning cardboard disk that created the illusion of movement when viewed in a mirror. In 1834 William George Horner invented the zoetrope, a rotating drum lined by a band of pictures that could be changed. The Frenchman Émile Reynaud in 1876 adapted the principle into a form that could be projected before a theatrical audience. Reynaud became not only animation’s first entrepreneur but, with his gorgeously hand-painted ribbons of celluloid conveyed by a system of mirrors to a theatre screen, the first artist to give personality and warmth to his animated characters.

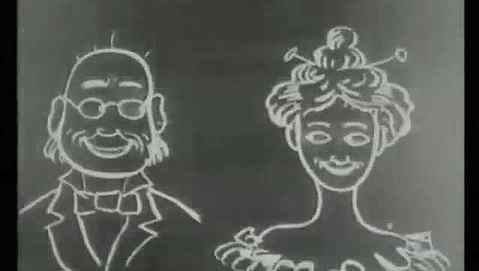

With the invention of sprocket-driven film stock, animation was poised for a great leap forward. Although “firsts” of any kind are never easy to establish, the first film-based animator appears to be J. Stuart Blackton, whose Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906 launched a successful series of animated films for New York’s pioneering Vitagraph Company. Later that year, Blackton also experimented with the stop-motion technique—in which objects are photographed, then repositioned and photographed again—for his short film Haunted Hotel.

In France, Émile Cohl was developing a form of animation similar to Blackton’s, though Cohl used relatively crude stick figures rather than Blackton’s ambitious newspaper-style cartoons. Coinciding with the rise in popularity of the Sunday comic sections of the new tabloid newspapers, the nascent animation industry recruited the talents of many of the best-known artists, including Rube Goldberg, Bud Fisher (creator of Mutt and Jeff) and George Herriman (creator of Krazy Kat), but most soon tired of the fatiguing animation process and left the actual production work to others.

Britannica Quiz

Saturday Morning Cartoons and More

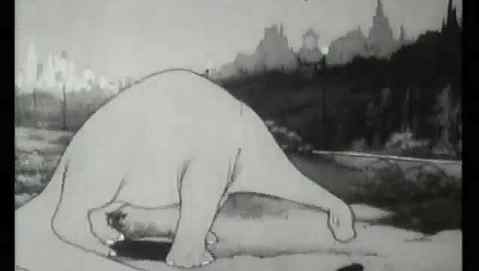

The one great exception among these early illustrators-turned-animators was Winsor McCay, whose elegant, surreal Little Nemo in Slumberland and Dream of the Rarebit Fiend remain pinnacles of comic-strip art. McCay created a hand-coloured short film of Little Nemo for use during his vaudeville act in 1911, but it was Gertie the Dinosaur, created for McCay’s 1914 tour, that transformed the art. McCay’s superb draftsmanship, fluid sense of movement, and great feeling for character gave viewers an animated creature who seemed to have a personality, a presence, and a life of her own. The first cartoon star had been born.

McCay made several other extraordinary films, including a re-creation of The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), but it was left to Pat Sullivan to extend McCay’s discoveries. An Australian-born cartoonist who opened a studio in New York City, Sullivan recognized the great talent of a young animator named Otto Messmer, one of whose casually invented characters—a wily black cat named Felix—was made into the star of a series of immensely popular one-reelers. Designed by Messmer for maximum flexibility and facial expressiveness, the round-headed, big-eyed Felix quickly became the standard model for cartoon characters: a rubber ball on legs who required a minimum of effort to draw and could be kept in constant motion.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Walt Disney

This lesson did not go unremarked by the young Walt Disney, then working at his Laugh-O-gram Films studio in Kansas City, Missouri. His first major character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, was a straightforward appropriation of Felix; when he lost the rights to the character in a dispute with his distributor, Disney simply modified Oswald’s ears and produced Mickey Mouse.

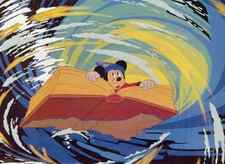

Far more revolutionary was Disney’s decision to create a cartoon with the novelty of synchronized sound. Steamboat Willie (1928), Mickey’s third film, took the country by storm. A missing element—sound—had been added to animation, making the illusion of life that much more complete, that much more magical. Later, Disney would add carefully synchronized music ( The Skeleton Dance, 1929), three-strip Technicolor ( Flowers and Trees, 1932), and the illusion of depth with his multiplane camera ( The Old Mill, 1937). With each step, Disney seemed to come closer to a perfect naturalism, a painterly realism that suggested academic paintings of the 19th century. Disney’s resident technical wizard was Ub Iwerks, a childhood friend who followed Disney to Hollywood and was instrumental in the creation of the multiplane camera and the synchronization techniques that made the Mickey Mouse cartoons and the Silly Symphonies series seem so robust and fully dimensional.

For Disney, the final step was, of course, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Although not the first animated feature, it was the first to use up-to-the-minute techniques and the first to receive a wide, Hollywood-style release. Instead of amusing his audience with talking mice and singing cows, Disney was determined to give them as profound a dramatic experience as the medium would allow; he reached into his own troubled childhood to interpret this rich fable of parental abandonment, sibling rivalry, and the onrush of adult passion.

With his increasing insistence on photographic realism in films such as Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), Dumbo (1941), and Bambi (1942), Disney perversely seemed to be trying to put himself out of business by imitating life too well. That was not the temptation followed by Disney’s chief rivals in the 1930s, all of whom came to specialize in their own kind of stylized mayhem.

MY STORY

Upon graduation from University of Central Florida (Go Knights!) with my shiny new Criminal Justice degree, I was convinced I’d immediately land a job in federal law enforcement since I’d successfully completed an internship with the U.S. Postal Inspection Service. On the day my “sorry, but we’re on a hiring freeze” letter arrived, the owner of a small animation studio coincidently saw my art hanging in my parents’ home while he was being given a tour (their home was on the market for sale). He hired me on the spot.

Until that moment, art had been nothing more than a hobby. Going forward, however, art would become my passion.

My time at the small studio was short-lived. I found myself at another studio and then another. I’m not sure what the success-rate stats are for small studios, but in Central Florida I can attest to how difficult it is for studios to stay afloat. Still, those years were invaluable for me. I worked alongside former Disney animators who didn’t move West when Disney closed their Florida-based animation studios. Their talent, their skill … the most amazing artists, visionaries, storytellers … I mean, wow.

Wanting to continue in art when yet another small studio closed its doors, but being apprehensive about committing to yet another, I sought a larger opportunity that I felt might be more stable. I landed a job at EA Tiburon (Electronic Arts) as a character artist creating human likenesses for games including NCAA Football and Madden. The job was amazing. Let’s just be honest for a second — if you know these games, then you know how fulfilling it is to say you’re part of the team contributing to the game.

During down times, when I had to wait for certain elements of the game to run their course before I could continue, I sketched. I sketched places I’d rather be. I sketched surf shacks, streams in forests, romanticized tree houses and even dreamed up a small brick gallery called Rob’s. Before long, my cube was covered with pen sketches on lined notebook pages. And though I sketched in black and white, my mind’s eye saw the works in color. My love of fine art (something that had been a hobby which landed me my first studio job) was returning. After work at EA, I turned several of those sketches into oil paintings.

Every hour that wasn’t spent at EA, I spent at the easel. With each painting, I sought to “up” the one before it with technique, lighting, composition, story.

When my time at EA came to a close for the 3rd year, I thought long and hard about my future. I asked myself if a future in studios was what I wanted? The answer was no. If I was honest with myself, I wanted to paint … full time.

I took a leap of faith. The hardest thing I ever did was tell EA no when they called again for the next cycle. It was scary as hell! Not going to lie. But it meant long hours and I knew that if I committed to EA, I wouldn’t have time to paint and build a body of works, which was essential to my longterm goal.

In the beginning, I painted lighthouses, shacks on the banks of rivers, manatees, airplanes. My subjects were all over the place. However, one thing remained consistent across all my works – a style resembling animation. My background in studio animation was without doubt showing through. Why not embrace that style? Who says animation can’t translate into fine art? Who says animation doesn’t equate to talent? Who says technique, lighting and composition can’t be strong in a painting that was meant to make the viewer smile? No one!

So, I began painting in a style that made me happy. Not a style that I thought would be popular or a style that would result in sales (although one can hope). I developed my style and perfected it and gave it everything I had.

When I first painted Beau the frog with his big, animated eyes and human-like expressions, I feared what the art world would think. Was he too simple? Was he too cartoony? Would other artists consider my style too childish and see no talent?

I took my first two Beau paintings (Hey You and Hey Me) to an art festival on the streets of Ocala. The reception Beau received by festival visitors blew me away. People liked him! They asked questions. They wanted to know his story. They wanted to buy him! Both originals sold on the first day of the festival and people were asking for prints.

I had no idea what other artists thought of Beau, but I knew that buyers (and now collectors) found happiness in Beau. They smiled when they saw him. THAT was all I needed to know.

Finally, I’d found my style (deemed fine art animation) and I’d found my subject (story-telling through light and characters).

I focused on those two things with every single painting going forward. Beau became so popular that, even when he wasn’t the feature of a painting, I started hiding him in scenes, such as the collection Places I’d Rather Be.

ANSWER THE QUESTION ALREADY

Now, here comes the Disney part. I know the lead-up was long, but I feel it’s important to know I didn’t originally set out to be a Disney artist, not even an artist.

If you’re still hanging in here with me, let’s review some of the points I hope artful hopefuls have taken. 1) Though I have a college degree, it is not in art. Go to school. Definitely go to school. Art school or not, a degree WILL open doors and at least get you the interviews. 2) Find your own unique style in art. Copying the styles of popular artists will get you absolutely nowhere, but being unique will turn heads. 3) Just because you’ve defined your own style does not mean you should ignore technique or composition which are important to all styles and mediums.

FIRST BE AN ARTIST

Before you try to be a Disney artist, just be an artist.

Again. Be an artist.

Before you do Disney, do you. Study. Learn. Develop your style. Paint. Don’t paint Disney. Paint you. Paint your own work, not someone else’s.

My opportunity with being a Disney licensed artist came via invitation. I received an invitation to paint a few trial Disney pieces because the powers-that-be liked the unique style and accomplishments that they saw in my existing body of work. My style was unlike anything they already had in their library of artists.

That invitation came because I had been doing my own thing and someone noticed. The invitation did not come because I had already been painting Disney on the side (which, by the way, profiting from this is of course a violation of trademark, copyright, you name it.). Don’t risk your future opportunity to proceed legally with a license. I see so many artists selling paintings of Mickey on Etsy or via Instagram. Seriously, “stealing” from Disney is not the way to communicate your commitment to their brand.

As a side note, I even found (thanks to a fan who spotted it and shared the link with me) an “artist” painting replicas of one of my Disney works and selling them as originals on Etsy. Aside from not painting my signature, the work was not altered in any way. Because this violated more than just my own copyright, the publishing company from Disney became involved and letters were issued. The artist apologized saying, “I’m just a smalltime artist trying to make money.” I’m not unsympathetic to trying to earn a living … I am, however, unsympathetic to plagiarism, theft and general dishonesty.

I’m a Disney fan. 100%, passholder-style fan. Prior to my invitation, don’t think I had not taken notice of Disney art hanging on the walls of my favorite galleries. Don’t think I didn’t long to be “part of their world.” I knew, however, it was more important for me to stay true to my own paintings. I’d worked hard to build my career thus far and I’d taken a lot of risks, but I didn’t dare take for granted or jeopardize the opportunities I had earned by trying to skirt the law. That didn’t make sense.

When the right people took notice of my existing art, decided I might be a good fit and decided to give me a shot, I jumped!

Storing your Disney paintings

Considering how many paintings we have generated in the last 26 days, and how many more we plan on creating before self-isolation is over, it is important to have a safe place to store everything.

We quickly switched from canvas to sketch pad when we realized we would be making more than just a handful of paintings. Be mindful of the type of sketch pad you buy; the dollar store has a few packs for painting and some for crayons. I found the sketch pads at Walmart, in the kids’ toys aisle, to be the most sturdy once painted on.

They sell two types; Paint and sketch. I bought myself paint and the kids’ sketch since theirs is cheaper.

Also, just to make things more interesting, sketch pads come in 9 x 12 size and the standard page protector is 8 1/2 x 11, so unless you are painting on printer paper or plan on cutting the sheets down to size before making your creations, you will need a specific kind of project gallery.

I recently bought myself a presentation book and the kids a simple frame to hold their best artwork. Due to increased demand for other products, Amazon and similar companies have reduced their availability of non-essential products. These galleries, for example, are scheduled to arrive 30 days after placing our order. If you plan on making a lot of art, we suggest buying more than you currently need, considering it will take so long to get replenished.

Paint Supplies

Like my dad always said, “get good, then get fast”. This was meant for my driving lessons when I was 16 but the meaning is still there; start with cheap dollar store quality materials and slowly work your way to Michaels/Joanna $5 bottle paints.

Since the dollar store paints are thinner, they will dry much faster than traditional acrylic paints. Because they are thin, however, it makes it that much easier to see your lines under the paint. I like this, simply because I tend to draw my accent lines while I am sketching.

These paints do mix well together, which is great because they don’t sell a lot of the tones that Disney is known for. The colour also comes out matte, instead of glossy or satin. Not a deal-breaker but your paintings will come out noticeably different than your inspiration for this fact alone.

Regardless, we are having a great time painting Disney characters, despite our lack of skills, and we hope this post acted as a bit of encouragement; If I can paint half-decent pictures, there is hope for your family.

We will be sharing more of our incredible creations. Join our Disney Facebook group and share some of your creations.

Your Thoughts.

Please share your thoughts in the comments or reach out on social media. We would love to hear from you.

Follow Mouse Travel Matters for Disney Parks news, the latest info and park insights, follow MTM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

You May Also Like…

- Disney World Packing List Florida Gets Cool

- Autograph Creative Things from Disney Characters

- Managing Your Child’s Souvenir Budget at Walt Disney World

- How Can I Get From My Disney World Resort to Universal Studios?

- Top 5 copycat Disney recipes to try at home.