At Katsukawa’s studio, Hokusai was tasked with producing prints from kabuki and images of sumo wrestlers. He was not among the most favored of the apprentices, however, and so was given off-season performances to depict and cheap paper and low-standard pigments with which to work. While working here, Hokusai published his first series of prints, of kabuki actors, in 1779, and married his first wife, about whom little is known.

Ukiyo-e: The Floating World of Japanese Art Prints and Its Symbolism

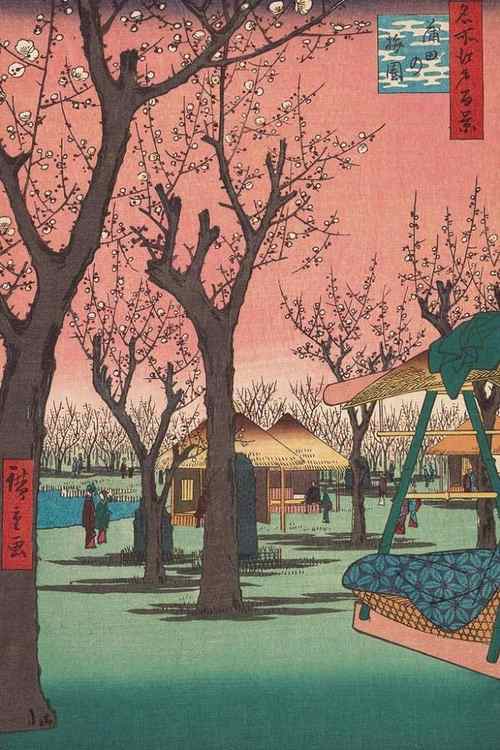

Ukiyo-e , directly translating to “pictures of the floating world,” embodies the concept of “ukiyo,” a term originally rooted in Buddhist philosophy. Historically, “ukiyo” described the suffering of life, but over time, its connotation shifted in the Edo period to symbolize the transient, fleeting nature of worldly pleasures and desires. These Japanese prints of a “floating world” represented a hedonistic urban lifestyle, marked by entertainment, leisure, and ephemeral beauty, particularly in the pleasure districts of cities like Edo (modern-day Tokyo). In essence, ukiyo-e captures this evanescent world in vibrant visuals.

Symbolism in Japanese Ukiyo-e prints

Japanese prints, in their exquisite detail and vivid imagery, have long been a testament to the nation’s profound connection to the natural world. This affinity for nature is deeply rooted in Japan’s cultural and spiritual fabric, a reflection of centuries-old traditions and beliefs. Within these prints, elements like cherry blossoms stand out not just for their aesthetic appeal but for their symbolic weight. These delicate flowers, in their transient bloom, encapsulate the fleeting and cyclical nature of life, serving as a poignant reminder of its impermanence. In stark contrast, the majestic Mt. Fuji, often depicted with an air of reverence and awe, symbolizes enduring strength and permanence. Artists like Hokusai have immortalized this iconic mountain in their works, capturing its unchanging presence amidst the ever-evolving landscapes. Through such portrayals, Japanese prints convey a dual message: a celebration of the transient beauty that surrounds us and a deep respect for the eternal forces that anchor our existence.

See Product

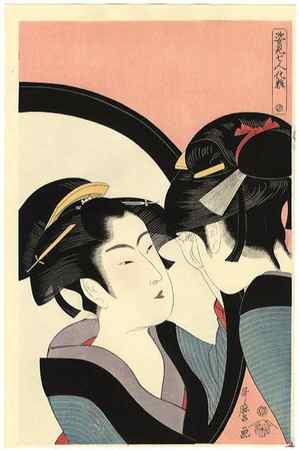

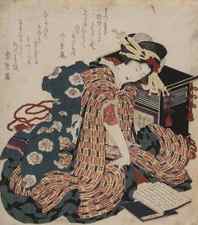

Beautiful Women (Bijin-ga)

Japanese art prints, particularly those featuring women such as courtesans and geishas, offer a complex and multifaceted portrayal of femininity. Beyond their undeniable aesthetic allure, these prints carry profound undertones that transcend mere visual representation. The delicate and ephemeral beauty of these women, as captured in the intricate details and nuanced expressions, serves as a poignant reminder of the transient nature of beauty, an aspect deeply ingrained in Japanese culture and aesthetics. Yet, there’s an additional layer to these portrayals. The poised postures and serene faces often mask a deeper commentary on the societal constraints and expectations placed upon women. The lavish kimonos, intricate hairstyles, and elaborate accessories, while beautiful, can be seen as symbolic of the societal shackles that both celebrated and confined them. Through these Japanese art prints, artists deftly wove a narrative that simultaneously exalted the beauty and grace of these women while also shedding light on the challenges and limitations they faced within the societal framework.

Summary of Katsushika Hokusai

Hokusai is widely recognized as one of Japan’s greatest artists, having modernized traditional print styles through his innovations in subject and composition. His work celebrated Japan as a unified nation, depicting a diversity of landscapes and activities linked by shared symbols and stories. He was among the first artists to be shaped by and to shape globalization, drawing from international influences and, later, being embraced by European artists who borrowed his decorative motifs, his practice of working in series, and his vision of contemporary society. To this day, a plethora of artists continue to reckon with his legacy.

- Hokusai introduced European perspective to Japanese printmaking, often taking a significant focal point and arranging his prints around this. He used various framing mechanisms to emphasize these focal points and create depth in his images. While twenty-first century viewers are used to seeing prints arranged in this way, the technique was unprecedented in Hokusai’s day and it was due to his influence that it became a widespread tactic in Japanese printmaking.

- Hokusai moved the Ukiyo-e genre, images of ephemeral pleasures, from traditionally being focused on people to highlighting landscapes and the changing seasons. His designs for prints encouraged audiences to bear witness to elusive moments of change in nature, capturing birds, flowers, and moving water, combining an attention to the fleeting with an awareness of the timeless.

- Mount Fuji was a central symbol in Hokusai’s work and he found a wide range of ways in which to depict the mountain. This repetition created a unity between the different scenes of Japanese life represented by the artist. His ability to return to the same subject whilst creating a diversity of images shows his compositional and creative prowess.

The Life of Katsushika Hokusai

Hokusai’s most famous image is The Great Wave of Kanagawa which can be found across our visual culture – it continues to be sold as a print from homeware store Ikea. But beyond this masterpiece, numerous details in Hokusai’s prints are well worthy of our attention.

Read full biography

Read artistic legacy

Important Art by Katsushika Hokusai

Progression of Art

1814

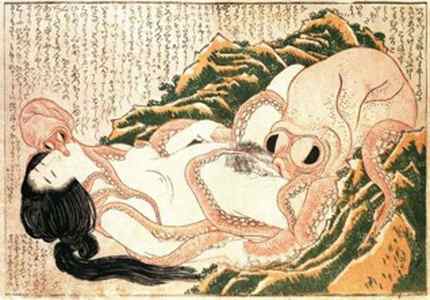

The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife

In this woodcut, a woman is shown reclining, her head tilted back toward the left side of the frame and her black hair tied back, as two octopi envelop her body. The larger of these, on the right, is shown performing cunnilingus, holding the woman’s body in place with tentacles wrapped around her legs, torso and arms, while the smaller octopus, close to her cheek, stimulates her left nipple and mouth. There appear to be rocks on either side of the group and the space around the illustra-tion is filled with tightly distributed text detailing a story in which an octopus informs a woman that he will be taking her to an undersea palace.

This image is a particularly impressive example of the erotic genre known as ‘shunga,’ which translates literally to the euphemistic ‘pictures of spring,’ which was particularly popular in the nineteenth century. The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife was and continues to be popular primarily due to Hokusai’s skill in capturing female pleasure, with the open position of the woman’s body, her reclining head, closed eyes and open mouth evoking her sense of abandon and inspiring viewers’ own flights of fantasy.

In addition to providing titillation to viewers, such images were seen as offering protection to the owner. The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife was published in a volume of shunga published by Hokusai in 1814; he continued work in this genre until 1821, by which point he had published three volumes. While European critics have often mistakenly labelled the scene a rape, the text makes clear that this is a scene of mutual pleasure. It is likely that contemporary Japanese viewers would have been reminded of a popular story about a pearl diver who descends to an undersea palace, pursued by sea creatures, to save a stolen pearl belonging to her lover.

Hokusai’s work improved as he aged, taking in diverse influences from both Japanese and European art. He became more ambitious after his brush with death at age fifty, in 1810, moving away from the kabuki prints that allowed him steady work and breaking new ground in printmaking. Due to this, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife and the other prints for which he is best known were made fairly late in his career.

c. 1830-31

Fine Wind, Clear Weather

This comparatively simple print is dominated by the cone of Mount Fuji, which reaches its apex toward the right side of the composition. The mountain is shown in the deep red that occurs only during the rare sunrise in late autumn when the weather is clear and the wind is southerly, as is alluded to in the title, Fine Wind, Clear Weather. The red, accented with traces of snow toward the top of the volcano, is balanced by the adjacent blue sky, streaked with clouds, while the base features both a wash of light green shaded by a forest of darker dots. The steep, triangular mass of the mountain is carefully balanced by the rounded horizontal clouds to the left, while the parting of these clouds around the summit gives it emphasis.

Fine Wind, Clear Weather is from Hokusai’s best-known series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. Mount Fuji had long been a site of veneration, but in Hokusai’s time the demand for images increased as pilgrimages became accessible to the growing middle-class population of Edo. This print elegantly captures the grandeur of Mount Fuji; the simplicity of composition, with no distractions from the central subject, serves to emphasize the height and steep slope of the mountain, while the small trees at the base provide a sense of scale. There is no sign of human presence in the image, positioning nature as complete in itself, requiring no additions. The scene is at once fleeting, due to its meteorological precision and the rare nature of the light, and timeless, able to repeat across centuries and requiring no human intervention. Hokusai, here, positions the viewer as if they are a traveler, bearing witness to the spectacle of nature.

This series became well-known and popular internationally. Its influence can be seen in France, where Henri Rivière, in 1902, created a series of prints directly based on Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji entitled Thirty-Six Views of the Eiffel Tower. Rivière borrowed Hokusai’s ap-proach, drawing scenes from a range of vantage points, but replaced Japan’s natural landmark with France’s industrial symbol, then relatively new. More recently, Jeff Wall has reconfigured Hokusai’s work in his photograph Sudden Gust of Wind (After Hokusai), which replaces the delicate cone of Mount Fuji with a flatter, dull landscape outside Vancouver.

Color woodblock print – Minneapolis Institute of Art

1830-32

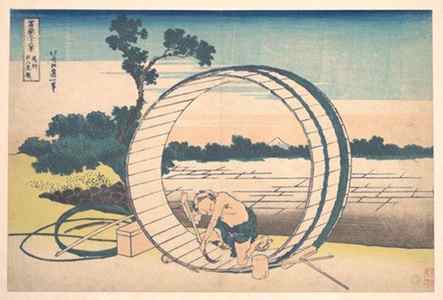

Fujimigahara in Owari Province

In Fujimigahara in Owari Province, from the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, a man works on a large barrel against a backdrop of fields, trees and Mount Fuji, framed in the distance by the circular frame of the barrel. The man, kneeling on the barrel as he works, appears old and wizened; his shoulders rise above his head and his limbs are characterized by sinewy lines. He wears a headband, ragged clothing around his waist and simple sandals. The colors used in the print are pale, with the land, the barrel and the man himself represented in light yellow and beige tones and the sky above streaked incompletely with blue, while the dark green foliage creates a central line over which the cone of Mount Fuji, in blue and white against a beige sky, peeks.

This print celebrates the everyday life of the worker, with his inadvertent framing of Mount Fuji, behind his back, providing both compositional satisfaction and a dose of humor, as the man turns away from the very spectacle that his barrel, and the print, frames. Ukiyo-e, as a genre, often focused on scenes of ephemeral pleasure, and Hokusai’s depiction of the barrel maker simultaneously did this, giving the figure the appearance of contentment in both his facial expression and in his apparent ease working outdoors with minimal clothing, and subverted this, offering a scene in which rural life is presented as timeless and unchanging, with no visible indicators of modernity in dress, landscape or industrial process. The symbol of the mountain, appearing in each of the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, serves to unify disparate regions, landscapes and ways of life in Japan and links the archipelago’s past and present, further solidifying its status as a national symbol.

Color woodblock print – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

c. 1829-32

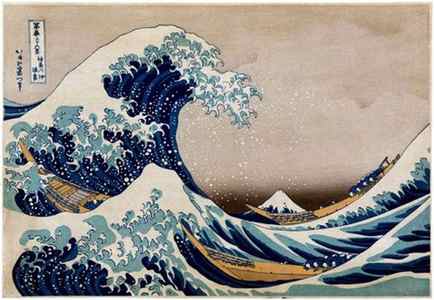

Great Wave off Kanagawa

Great Wave off Kanagawa is Hokusai’s best-known print and quite possibly, the most famous art-work from Japan, of all time. The print shows Mount Fuji, in the background, framed by the rough seas off the region of Kanagawa, which roll and froth against a grey sky. The viewer is presented beneath the largest wave, which masses toward the left side of the image and breaks into claw-like foam toward the top of the print, scattering spray into the sky in front of the mountain. The eye spi-rals outward from the mountain, at the center, drawn along the line created by the broken wave, which moved down and inward, toward the base of the mountain, before turning upward toward the right edge of the print, encouraging the viewer to move back into the image, creating a sense of motion much akin to being caught on a rolling sea. The height of the waves is emphasized by three fishing skiffs within the swell, each with a number of small figures onboard, that threaten to be submerged or overturned.

The moment which Hokusai has chosen to depict, when the wave is on the brink of breaking and of obscuring Mount Fuji, on the horizon and consequently much smaller than the wave, heightens the tension in the image. Hokusai, instead of deploying the traditional bird’s eye perspective used in Japanese prints, as he had in earlier sketches of waves, uses mathematical perspective – in which objects that are further away are shown as smaller – to create a sense of depth in the image and puts the viewer “inside” the scene. Hokusai had been experimenting with European approaches to perspective since encountering the work of Shiba Kokan, in the 1790s, who had studied Dutch works at Nagasaki in the 1790s, when it was the only port open to foreigners. The wide range of blue tones deployed by Hokusai, also, was made possible by the introduction of Prussian blue to Japan during Hokusai’s lifetime.

Color woodblock print – Minneapolis Institute of Art

c. 1834

Bullfinch and Weeping Cherry

This print shows a bullfinch on a slender branch of cherry blossoms, angled downward, against a deep blue background. The bird’s beak reaches toward the bottom of the frame, while the claws that support his body allow his tail to extend upward. The branch itself, covered with buds, blooms and leaves, extends from the upper left of the image and follows the left edge before curving toward the right to fill the lower third of the frame. In the upper right, framed by the branch, is a haiku by Sugano Joyu II, which reads:

one single bird,

wet with dew

has come out:

the morning cherry.

Bullfinch and Weeping Cherry is from a series entitled Small Flowers which consists of a number of prints uniting formal realism with aesthetic elegance. The print, like those alongside it, shows Hokusai’s participation in Japanese traditions of representation and his interest in finding new ways of depicting familiar subjects, such as birds and flowers. Hokusai’s most striking innovation, here, is the representation of the haiku within the print itself; while other Ukiyo-e artists, including Utamaro and Kunsai, had illustrated books, Hokusai was the first to present the poem as a part of the image, creating a dialogue between text and visual art that would have an ongoing impact. Hokusai’s delicate treatment of the branch, too, with curves used to decorative effect, went on to have an influence on the decorative arts internationally, with Art Nouveau graphic and interior design drawing heavily from the use of nature as a framing device.

Color woodblock print – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, USA

1847

Ducks in a Stream

Ducks in a Stream, painted when Hokusai was 87, shows two mallards diving into a stream of water in search of food. In the center of the vertical scroll, which encourages the eye to move downward, one duck is shown above the water, both body and beak clearly visible to the audience, while another duck, beneath, dives through the diagonal lines that signify the rushing water. The ducks are depicted with a great deal of detail and color while the stream is represented only by eight bands of grey, with shadows of weeds surrounding the birds themselves and red maple leaves floating atop the surface, suggesting it is autumn.

Despite the simplicity of the composition, Hokusai’s approach is experimental, combining a naturalistic approach to the birds, which are built up with small strokes of paint, with a more symbolic and sparse treatment for their fluid environment. The depths and motion of the water is suggested through the modulated washes of grey and the shifts in brightness and clarity to indicate the positioning of the water itself. The work’s meaning is somewhat ambiguous, with Hokusai seemingly overlooking the traditional association of ducks with marital fidelity in favour of a more straightforward representation of the natural world in which the birds hint, instead, at the changing of seasons and passing of time, evoking an emotional response.

Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk – The British Museum, London

1849

Li Bai Admiring a Waterfall

Li Bai Admiring a Waterfall was produced shortly before Hokusai’s death and depicts Tang dynasty poet Li Bai, his back to the viewer and his head and body obscured by traditional hat and dress, standing on a slope and staring at a tall waterfall that streams before him. The subject is drawn from the poet’s poem ‘Viewing the Waterfall at Mount Lu,’ which presents a waterfall, and nature more broadly, as having a spiritual significance. The water, here, falls from a point beyond the upper edge of the frame and falls in neat, graceful lines and soft greys, cool and calming. There are traces of spray in the foreground, though they are unobtrusive, and speckles of rock appear beside the waterfall, to the right. On Li Bai’s right, almost blending with his own clothing, is the figure of a child clinging to him.

This image reflects the increasingly global position of Japan, drawing its subject from Chinese poetry whilst utilizing a traditional Japanese technique. Hokusai’s modern approach to composition and nature is clear, with the extended strokes of the waterfall drawing the audience into the image and positioning nature itself as possessing spiritual power. Hokusai’s interest in both abstraction, in the extended strokes of the waterfall carrying the eye downward, and naturalism, in the splash of water at the base of the scroll, can be seen here. Li Bai’s mystery, synonymous with the mystery of artistic creation, is alluded to through the audience’s inability to see the poet’s face.

Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, USA

1849

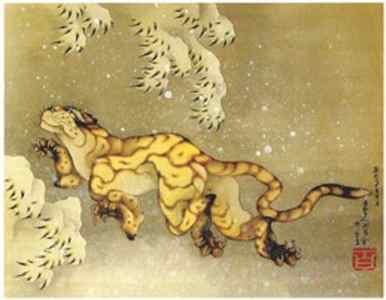

Old Tiger in the Snow

This painting shows a tiger, moving from right to left, claws exposed and body and fur rippling, muscular though seemingly boneless. The tiger is painted in gold and brown, with a paler stomach and chest. There is no sign of the ground, though the flecks of white in the air above the tiger and the foliage on the left and upper edges of the image suggest that the creature is floating through a snowy landscape. The sharp ends of the plants, protruding from the snow, mirror the sharp claws of the tiger, all of which are exposed to the audience.

Old Tiger in the Snow is one of Hokusai’s last works and can be read as autobiographical, expressing Hokusai’s feelings on his own age and the process of aging. The red seal in the lower right corner reads ‘100,’ a detail which some critics have suggested could mean Hokusai was willing himself to live longer. The tiger, too, can be seen as a representation of the artist’s energy and ambition, at an advanced age or as he moves into the afterlife. The tiger holds its head high and has a satisfied expression on its face as he moves forward with no sign of slowing down, suggesting contentment and fearlessness.

Woodcut – Private Collection