Partial Separatist: Federal and state governments should be permitted to grant aid to religions for only certain secular purposes (such as teaching remedial reading and math).

Articles

At this time, the Church of England (also known as the Anglican Church) was the established religion of Virginia. This meant that the Anglican Church was the only officially recognized church in the colony. Virginia taxpayers supported this church through a religion tax. Only Anglican clergymen could lawfully conduct marriages. Non-Anglicans had to get permission (a license) from the colonial government to preach.

Although the Anglican Church was the sole established church in all five Southern colonies, other protestant Christian churches became established in the towns of the Northern colonies of New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Each town chose by majority vote one Protestant church to be supported by taxpayers. In these colonies, one church usually predominated. For example, in Massachusetts almost all towns selected the Congregational Church since the majority of people living in the colony belonged to that faith.

Thus, on the eve of the Revolutionary War, nine of the 13 colonies supported official religions with public taxes. Moreover, in these colonies, the government dictated “correct” religious belief and methods of worship. Religious dissenters, like “Swearing Jack,” were discriminated against, disqualified from holding public office, exiled, fined, jailed, beaten, mutilated, and sometimes even executed. Only Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware did not have a system linking church and state. After the Revolution, leaders like Jefferson and Madison worked to ensure freedom of religion for all citizens of the new nation.

The Struggle for Religious Freedom in Virginia

During the Revolutionary War, all Southern states ended the Anglican Church’s monopoly on religion, but they continued to financially support Christian churches in general. Virginia, however, moved to separate church and state after the Revolution.

A year after Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence, he wrote a bill on religious freedom for his home state of Virginia. In writing these documents, Jefferson was strongly influenced by the 17th century English philosopher John Locke. In 1689, Locke had argued that “the church itself is a thing absolutely separate and distinct from the commonwealth [government].” Taking this idea from Locke, Jefferson proposed that Virginia end all tax support of religion and recognize the natural right of all persons to believe as they wish.

Jefferson introduced his bill to the Virginia Assembly in 1779, but state lawmakers did not consider the matter of church and state until after the Revolutionary War. In 1784, another Virginia patriot, Patrick Henry, proposed making Christianity the established religion of Virginia. After failing to get the General Assembly to pass this proposal, Henry submitted another religion bill that called for a tax supporting all Christian churches in the state. Henry felt this would improve public morals, which he thought had declined during the Revolution.

Under Henry’s bill, taxpayers could designate their tax payment to go to the Christian church of their choice. Henry’s bill probably would have passed had not Jefferson’s ally, James Madison, persuaded the General Assembly to delay voting until the following year (Jefferson was in Paris as U.S. ambassador to France).

During spring and summer of 1785, Madison worked to sway public opinion against Henry’s religious tax bill. In a widely circulated petition against the bill, Madison declared that it was the natural right of all persons, even atheists, to be left to their own private views of religion. He argued that throughout history “superstition, bigotry, and persecution” have accompanied the union of religion and government. He also asserted that Christianity did not need the support of government to flourish.

Baptists and other evangelical religious groups in Virginia also circulated petitions against the religious tax bill. They viewed this bill forcing government into church affairs and threatening religious liberty. Overwhelmed by the negative public response to Henry’s bill, the General Assembly did not even bring it up for a vote. Instead, Madison reintroduced Jefferson’s bill, which called for severing all ties between the state of Virginia and religion. Jefferson’s “Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom” was passed on January 19, 1786. This was the first time that a government anywhere in the world had acted to legally separate religion from the state.

“A Wall of Separation”

As written in 1787, the U.S. Constitution did not mention religion except to prohibit any religious requirement for holding federal office. When the first Congress met in 1789, Madison proposed a series of amendments to the Constitution guaranteeing the rights of Americans. The opening words of the First Amendment declared that, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. . . .” The First and other nine amendments, called the Bill of Rights, were ratified in 1791 as part of the Constitution.

The Bill of Rights originally only limited acts of the federal government. Thus, the First Amendment’s prohibition against laws “respecting an establishment of religion” did not affect what states could do. Consequently, seven states (including newly admitted Vermont) continued to assess taxes in support of Christian churches. State laws also frequently required public officeholders to be Christians, denied the vote to non-Christians, and enforced the Christian Sabbath.

When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, he tried to maintain a strict separation between government and religion in federal matters. He was criticized for refusing to proclaim a national day of prayer and thanksgiving as presidents George Washington and John Adams had done before him. Jefferson wrote a letter to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, to explain his views on religion. In this letter, he quoted the First Amendment’s clause prohibiting Congress from passing laws establishing religion. Jefferson then remarked that this establishment clause built “a wall of separation between Church and State.”

Where Should the Line Be Drawn?

Gradually, all states followed the lead of Virginia in ending religion taxes. Massachusetts in 1833 was the last of the original 13 states to do this. But some states still involved themselves with religion. For instance, several states made recitation of the Lord’s Prayer and devotional Bible readings mandatory in public schools.

Not until the 20th century did the U.S. Supreme Court apply most of the Bill of Rights to the states. The Supreme Court has ruled that the 14th Amendment (ratified in 1868) requires states to guarantee fundamental rights such as the First Amendment’s prohibition against the establishment of religion. This means that states, like the federal government, can “make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

In 1947, the Supreme Court attempted to define the “establishment of religion” clause of the First Amendment. Justice Hugo Black, writing for the court, held:

Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. . . . In the words of Thomas Jefferson, the clause against the establishment of religion by law was intended to erect a “wall of separation between Church and State.” [Everson v. Board of Education (1947).]

Some constitutional experts dispute Justice Black’s definition of the establishment clause. They argue that “an establishment of religion” only prohibits the federal and state governments from supporting a national church or preferring one religion over others. In a 1985 case, current Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist stated in a minority opinion, “The Establishment Clause did not require government neutrality between religion and irreligion [no religion] nor did it prohibit the federal government from providing nondiscriminatory aid to religion.” [Wallace v. Jaffree (1985).] Rehnquist and others take the position that government may aid all religions or religion in general as long as no groups suffer discrimination.

The Supreme Court still struggles today over exactly where to draw the line separating church and state. On the one hand, the Supreme Court has struck down state laws providing for organized prayer in the public schools. But the court has also upheld laws that exempt churches from paying taxes.

For Discussion and Writing

-

How were Baptists and other dissenting religious groups discriminated against during colonial times?

For Further Reading

Levy, Leonard. The Establishment Clause, Religion and the First Amendment. Chapel Hill, N. C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Stanton, Evans M. “What Wall?” National Review. Jan. 23, 1995:56+.

ACTIVITY: Drawing the Line Between Church and State

A. Form small groups to discuss the following laws and government acts concerning church and state. Each student should keep a record of his or her opinions on each.

Do you agree or disagree that:

1. States should be allowed to enact religion taxes with proceeds going to the religion each taxpayer chooses?

2. Churches should be exempt from paying taxes?

3. Federal aid should be granted to religious colleges, charities, and hospitals for secular (non-religious)

purposes?

4. States should be allowed to require prayers or other religious exercises in the public schools?

5. The president should be allowed to proclaim a national day of prayer?

6. Cities should be allowed to permit churches to place nativity scenes in public parks at Christmas time?

B. Every student should review his or her opinions on the laws and acts and then choose which position below best reflects his or her opinion on the separation of church and state.

Establisher: By majority vote, states should be permitted to establish a single official religion supported by all taxpayers.

Accommodator: Federal and state governments should be permitted to support and aid all religions as long as none are favored or discriminated against.

Partial Separatist: Federal and state governments should be permitted to grant aid to religions for only certain secular purposes (such as teaching remedial reading and math).

Absolute Separatist: Neither federal nor state governments should become involved with religion in any way.

C. After making a choice, students should regroup according to their position and hold a class discussion on their views of separating church and state.

D. Finally, each student should write a persuasive letter to one of the article’s historical figures who differs with the student’s position on separating church and state. Establishers should write to “Swearing Jack” Waller. Accommodators should write to James Madison. Partial Separatists should write to Thomas Jefferson. Absolute Separatists should write to Patrick Henry.

The purpose of the letter is to try to convince the historic figure to agree with the student’s position.

An author’s story that shows faith is a gradual process

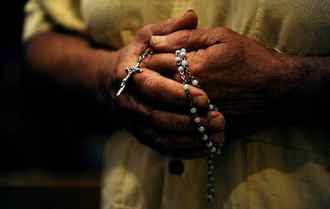

Surfing the (Catholic) net is not a mindless occupation. You can stumble on some wonderful articles; indeed, depending on what you read and your state of mind when you read it, an inspiring personal account of faith might be enough to trigger a change in your life. The internet, despite its reputation for easy corruption, can be a school of evangelisation just as any other means. The trick, as with choosing friends, is to select sites that encourage “the better angels of your nature” rather than those which merely confirm – or feed -your personal weaknesses or vices.

By way of this preamble I came across a most uplifting article yesterday on CFNews. I then discovered it had been written earlier this year for the Christendom Awake website. Entitled How I became a Catholic, it was by author and journalist Philip Trower. I happen to have known Philip for nearly 25 years and have enjoyed reading his two very informative books about the Second Vatican Council: Turmoil and Truth and The Catholic Church and the Counter-Faith. Now aged 91 he is one of the few people I would describe as genuinely “saintly”: gentle, wise and charitable, all his conversation is about God and his love for the Church. He radiates faith.

His essay on his conversion is as thoughtful, reflective and candid as one would expect it to be. Like Evelyn Waugh, whose Face to Face interview with John Freeman, I blogged about recently, Philip had come to see that “all converts become Catholic for the same reason…they come to realise that the Church is what it claims to be: the sole authorised guardian and disseminator of the one true revelation of God to men through which they can know with certainty the purpose of their existence and their final destiny.” Such a statement tends to stick in the throat of ultra-ecumenists but it still remains true, as any Catholic, cradle or converted, comes to recognise.

Philip’s detailed memory of the steps and phases of his spiritual journey also reflects the truth that faith is a gradual process, both taught and caught in different ways that will bear fruit often years later. From a prosperous and distinguished legal family, he went to prep school, Eton and Oxford, absorbing the Anglican rituals of his time and class but also influenced by a devout and loving Catholic nanny, a French Catholic governess and other Catholic personalities he met in his youth. One amusing anecdote describes the period before he went up to Oxford, when he discovered in his father’s study a book by an ancestor of his, a former Bishop of Gibraltar in the early 19th century, entitled Trower on the Epistles. Opening it at random he read the phrase, “as the Church of Rome so wrongly maintains” and writes that he experienced “a sudden, intense feeling of irritation”. The seeds of his later conversion were already apparent.

Another moment came at Oxford when, in personal turmoil, he spoke to a don he knew who, although not a Catholic, told him “You will never find love until you find it in the tabernacle.” Recalling this incident years later Philip was amazed that at the time these words did not make a greater impression on him.

Then, at the end of the war, in which he served and was wounded in Italy, he met the man who was to prove the final catalyst for his conversion: the American, lapsed Catholic poet and homosexual, Dunstan Thompson. Philip admits that he had been living a homosexual lifestyle already; the two became lovers and set up home together in a little village in North Norfolk, near Walsingham.

In 1950 Dunstan began to recover his childhood faith, reading widely and receiving instruction from a priest in Farm Street, London. By 1952 he had returned to the Church. Philip relates that from then on they made the decision to live together chastely as friends and to distance themselves from the “gay culture”, although not from individual friends. He himself entered the Church at Farm Street in 1953. From then on, until Dunstan’s death from cancer in 1975, both men used their gifts, their time and their energy in apostolic work for their local parish and for the wider Church.

One anecdote that Philip told me, which he does not include in his essay, relates that before Dunstan made a renewed profession of faith he and Philip once happened to be in Walsingham (which had been one of the most famous Catholic shrines in medieval England) as a procession of the Blessed Sacrament was passing by. Dunstan instinctively went down on his knees; observing this Philip realised that his friend’s faith was more important than he knew or was prepared to admit at the time and it made a deep impression on him.

Perhaps at that moment in Walsingham, Dunstan began to recover the “love” that, as the Oxford don had told Philip some years before, can only be found “in the tabernacle” – and which was to draw Philip himself into the same Church in which, for the last 60 years, he has been a faithful and devoted member.

The Catholic Herald comment guidelines

At The Catholic Herald we want our articles to provoke spirited and lively debate. We also want to ensure the discussions hosted on our website are carried out in civil terms.

All commenters are therefore politely asked to ensure that their posts respond directly to points raised in the particular article or by fellow contributors, and that all responses are respectful.

We implement a strict moderation policy and reserve the right to delete comments that we believe contravene our guidelines. Here are a few key things to bear in mind when com menting…