Hi Char, I am starting over on the glass rose. The base color is 50/50 Prussian Blue and Phthalo. All M. Graham watercolor. The mix gives the same hue as the background of the glass rose picture. The adding of water gives the varying tone needed. If you look closely at the rose itself you will see the glass causes refraction, (slight shift in hue.) I found a article about color mixing and the use of Alizarin Crimson darkens the mix for the almost black ( very dark blue mix),sections in the rose. Here is the reference photo again. One of the other reasons for this mix is to allow a bit of transparency on the dark areas.

Look, Listen, Learn. Mixed-Up Color Mixing

Read the following story and teacher reflections, and use the Reflective Questions to deepen your thinking and shape your teaching practices.

One day, I invited a group of eight children to join me in a separate room to focus on an in-depth investigation of creating transformative art. My plan was to introduce the children to color mixing. I hoped to help them learn about primary colors and how other colors are made from them. I offered each child a tray with a piece of paper and six empty cups. In the middle of the table, I placed cups filled with the three primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—along with eyedroppers to use for transferring and mixing colors. I demonstrated for the children how to use the eyedroppers to combine colors in the cups to see what new colors they could create.

Realizing I had forgotten to offer paintbrushes, I walked over to the shelf to get some. When I returned to the table, the children had already started mixing colors—but not how I had planned. I was dismayed initially. Then, as I watched closely, I went from bemused to amazed at what I saw unfold. The children had bypassed the cups altogether and instead applied the paint directly onto the paper to mix the colors.

I watched as Cami took an eyedropper of red paint and squeezed a drop of it onto her paper. She then squirted blue paint onto the red. The colors began to combine and change.

Cami said excitedly, “Purple! Red and blue make purple!”

“Yep, that is exactly what combining the colors red and blue does; it makes purple,” I responded. “What happens if you mix red and yellow together?”

The children set about color mixing with gusto. They combined droplets of primary colors on the paper to make new colors. Again, the children had a different idea than I had planned. After adding more drops, they picked up their papers and waved them around to mix pools of paints together, making beautiful colors and swirling designs.

When the group met a few days later, they continued to be excited about color mixing. This time, they wanted to see what would happen if they added more blue to a mixture of purple. They were also curious about what would happen if they added yellow to the blue, and were excited by the green color they created. The vibrant colors they invented with their discoveries were stunning!

Next, I offered white and black paint, and the children eagerly investigated how they could make darker and lighter shades of the colors.

Laurie’s reflections:

When I started the color-mixing investigation, I hoped the children would learn that by mixing just a few colors, they could make many more. I wanted them to understand that most colors are made from just three primary colors. While planning, I eagerly imagined seeing their amazed reactions as they dropped each color into the containers, watching as a new color emerged.

In the classroom, I felt disappointed and anxious as they changed my beautiful, carefully constructed color-mixing activity. But soon, I began to hear oooh’s and ahhhh’s and to appreciate the wonder of discovery the children experienced as they created new colors. I made a conscious decision to sit back and just watch instead of stopping the way they were interacting with the materials.

I realized as I watched that they were having the exact learning experience that I was hoping for, just not the way I had planned. I sat with my hands over my mouth (yes, I really did this!), so I would not interfere with their process. I wanted to see and understand why all of the children had decided to mix the colors directly on the paper.

I saw that to the children, mixing the colors into the cups was an extra, unnecessary step. The children’s approach was different than mine; they experienced me as a “talking head.” Their way of working with the materials was more fun, and taking the initiative seemed to heighten their involvement and the intensity of their discoveries.

One of my goals for the color-mixing lesson was to offer children opportunities to interact and exchange ideas. I was uncertain whether their newfound approach would enable this. But I have to admit that the way I had presented the activity did not allow for much peer-to-peer interaction and would have ultimately failed to provide opportunities for collaboration. This was not an easy thing for a teacher to admit, but there it was right in front of my face. Instinctively, the children had transformed my activity into an active exchange of ideas:

Ellie: How do you make green?

Maura: You mix blue and yellow together.

Ellie: It’s not working.

Maura: I’ll come and show you. (Maura walks around the table and picks up two eyedroppers. She starts adding the colors together on the paper. Other children stop what they are doing and come over to watch how Maura makes green.)

Maura: You need to add more yellow, then blue to make a really bright green, see?

Ellie: Oh, I have an idea, keep dropping the colors.

Ellie then got a paintbrush and mixed blue and yellow together on the paper. Maura dropped more colors on the paper as Ellie directed her to add more and fewer drops of color. She started to laugh as they produced the color of green she wanted. I watched in amazement: the children were sharing ideas and techniques for mixing the colors!

As a teacher, I need to do more listening and watching. I realize that there are real reasons why children sometimes do not follow my instructions for activities. When this happens, I need to be humble enough to observe and try to understand why—even if it means admitting that having a preconceived way of completing an activity can get in the way of actual learning. As a teacher, I’ve learned that sometimes my plans will fail—and that’s alright. Now, I feel secure enough to fall on my face every once in a while, because it is during these moments that learning and growth happen, not just for the children but for me as a teacher.

As I go forward with explorations of different art materials, I am promising myself to try not to interfere when it looks like the children are changing my activity. I want to go with the flow.

Reflective Questions

Use the following questions from the Thinking Lens® to reflect alone or with a colleague.

Know yourself

- What is your reaction to Laurie’s story and her reflections on the children doing something different from what she had planned?

- What is your response when children explore art as a process rather than follow a lesson or replicate a product you have planned? Do you see the value in children’s investigations, like Laurie did?

- How often do you remind yourself to sit back and observe what is unfolding, like Laurie did? How would you assess your observation skills?

- What value do you see in offering children instructions and demonstrations for using art materials?

Find details of children’s competence

- What skills and competencies did you see in the children’s interactions with the materials and with each other?

- How did the children’s explorations offer more valuable experiences than Laurie’s initial plan? Were you surprised by the children’s competencies, as Laurie was?

Seek children’s points of view

- What was the children’s view of this situation? What do you think their ideas were about color mixing?

- How do you think the children saw Laurie’s plan and the way she offered the materials?

- How do the children in your group view you and the plans you make for them?

Consider opportunities and possibilities for next steps

- Try offering children a lesson in color mixing to see how they respond. How do the children react when you encourage them to stick to your plans? What do they gain from your instructions and demonstrations?

- At another time, offer children an open-ended way to explore color mixing. How do children respond when you let things unfold spontaneously? What competencies do they demonstrate when they initiate their own ideas?

- How does reflecting on these kinds of experiences help you enhance your view of children’s competencies and deepen your practice as a teacher?

Which colors blend to form the color blue?

Why do you need to use phthalo and prussian? And then the water. I’m really curious about the parameters you’ve set. If you can select another blue, then ultramarine with a hint of burnt sienna will create a beautiful dark, indigo-like, blue. Otherwise, mix an orange biased colour with your phthalo to get to the dark you’re looking for. Remember your colour theory, knowing that complements will neutralize one another. The only variable is the ratio of each colour.

Char — CharMing Art — “Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art.” Leonardo DaVinci

March 18, 2015 at 8:09 pm #1221517

Default

I’ll second what Char said, I use pyrrole orange in my phthalo blue all the time and it gives me a full range of blues that way. Also your requirements are strange – you don’t really need to use both blues together. I’d also like to know why you want those specific things, perhaps give us your overall objective and we can give you better alternatives. Indrathrene blue is also a good dark blue, but Phthalo is a lot more reliable and used full strength very dark. ( Indrathrene’s lightfastness varies, so you have to be very careful and repeatedly test when you get new paint, but then prussian has similar issues, phthalo is actually much more reliable ) You can mix some RGB style black with R a staining deep red ( perelene maroon, perm. Alizarian ) and G Phthalo Green ( or perhaps Perelene Green ) and that B phthalo blue or Indrathrene. Note that these are all just colors which used as mass tone get pretty close to black and that you can swap out similar colors and it will work just as well. This mixture can then be used to push that pthalo blue to be much blacker, and the perelene and Phthalo pigments are more stable then prussian is. You can probably use something like neutral tint to do the same thing, but it just does not have as much pop, and the other blacks you find in watercolor are made with materials that when they dry have a much duller texture, which prevents them from looking as rich of a black. Remember these are staining colors, so you can actually mix them on the paper in separate passes, as “layers” as well, slowly building up the darkness you are looking for and often giving very different results. I use this for example in sunsets to keep my yellow and blue from mingling too much and giving me green where they overlap, it still does it but it’s a lot less noticeable.

March 18, 2015 at 8:25 pm #1221520

Default

Hi Char, I am starting over on the glass rose. The base color is 50/50 Prussian Blue and Phthalo. All M. Graham watercolor. The mix gives the same hue as the background of the glass rose picture. The adding of water gives the varying tone needed. If you look closely at the rose itself you will see the glass causes refraction, (slight shift in hue.) I found a article about color mixing and the use of Alizarin Crimson darkens the mix for the almost black ( very dark blue mix),sections in the rose. Here is the reference photo again. One of the other reasons for this mix is to allow a bit of transparency on the dark areas.

. There’s a new day tomorrow and it hasn’t been touched yet.

March 19, 2015 at 9:24 am #1221513

Default

I was certain that I replied to you yesterday. My words are circling the ethernet for eternity… I can understand why you wanted to use the phthalo blue because it’s beautifully transparent. But pairing it with the prussian darkened and possibly dulled it. Also, the phthalo blue is a staining colour, making it quite a challenge to effectively create a smooth graduated wash in your background. Mixing alizarin with these blues will net you a violet. You can saturate the mixture until it appears to be black, but it will still be violet. Think about your colour theory. Complements neutralize one another. So, if you want to create a good quality dark with your phthalo blue, you’ll need to use an orange biased colour. Alizarin and phthalo green pair beautifully to make deep darks. I use that combination to enrich and deepen my red, create warm browns and of course a saturated black.

Char — CharMing Art — “Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art.” Leonardo DaVinci

March 19, 2015 at 11:36 am #1221519

Default

I need to mix a very dark blue from a 50/50 mix of Prussian blue and Phthalo blue. Plus there needs to be a mix of 50% water.

Humor the old man. Why? Lay out a puddle of Prussian Blue and slowly add drops of black India ink till you get the shade of blue you want. The puddle should be a bit on the thick side. I’ve never heard of the 50% water rule. Maybe I was absent that day? Aye? I have often drug India ink or even black liquid acrylic into my watercolors. But hey! That’s just me.

Glenn Koons

March 19, 2015 at 1:38 pm #1221514

Default

Glenn, india ink is permanent. I don’t think I’d add it to my watercolour until I practiced it on a piece of scrap paper.

Char — CharMing Art — “Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art.” Leonardo DaVinci

March 19, 2015 at 3:49 pm #1221518

Default

Adding ink like that is a japanese method long used in their styles of watercolor, but there are other ways to get the same effect. Generally japanese papers and watercolors are designed to work this way unlike western materials. This is in essence adding a “darkening neutral”, in this case ink, but you can use other colors like neutral tint, paynes gray, even actual black watercolors. Now phthalo blue is so dark in mass tone, that by repeated layers you can make it nearly black just by covering up the paper. This is kind of what you are doing with the purple combo – all of the very dark valued pigments are actually good at this. You should be able to get almost black with just using that phthalo blue alone. The phthalo green + alizarin ( permament ) combo Charm describes is just about as dark, as they are both dark valued to begin with in mass tone, and they are compliments which both dull and darken each other. Orange and blue together do something similar, but the various deep reds tend to be the darkest valued to begin with of the warm colors. Some of these compliments go perfectly gray, and are called neutralizing compliments, others just veer away from it and require a third color to get them neutral. The green and deep red/alizarin can veer towards brown but is nice and dark, and if you get the right combo is perfectly gray. ( Each brand is a little different. ) However add a bit of Phthalo Blue to that combo of green and red, it will darken it more and let you get it to perfectly neutral gray/black that can work much like india ink. If you just use the green+red mix as a darkening neutral for your blue, you are in effect getting this 3 color combination. However this is still a staining combo, another great combo for getting black is ultramarine blue and burnt sienna ( which are technically blue and a dull orange ) and you can use this as a darkening neutral, and it’s a bit easier to control as it’s liftable, but also does not go quite as dark since you can’t build it up in multiple layers as well. How you mix them can affect the results as well. You can mix colors in your palette, but also while they are still wet on the paper, but also you can let one color dry and mix them via glazes on top of each other. The order they are done as glazes can dramatically change how it looks.

March 20, 2015 at 12:23 am #1221515

Default

Richard, try Indanthrone Blue, by M Graham, I think it is almost the color of the background of your glass rose and it is very, very dark when used without much water but tames down a lot dilutes. I think you will like it….

Do Yellow and Blue Make Green?

Red, yellow, and blue are the three primary colors, the painter’s building blocks. You can mix every other color out of this trio. At least, that’s what they taught me in art class: combine any two primaries, and you get a “secondary” color, which lies between the primaries on the color wheel.

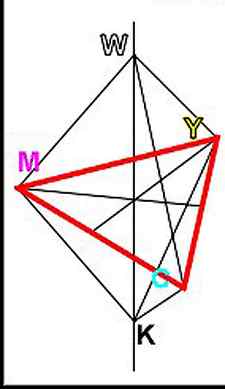

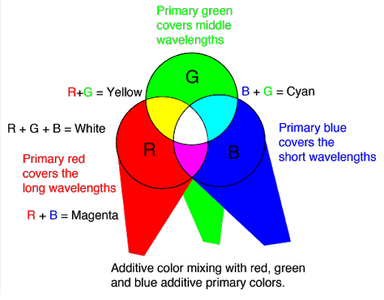

Then I picked up an optics textbook, and my world was turned upside down: the true primary colors are red, green, and blue. You can mix any hue out of these three shades of light. That’s how LCD displays work: by building pixels out of tiny sources of red, green, and blue light.

Why is the painter’s color wheel different? The textbook explained that light and pigments combine in opposite ways. Superimpose a blue and red spotlight, and the resulting light will emit blue and red wavelengths. Light mixes “additively.” By contrast, mixing paints is subtractive. A patch of red pigment is red because it absorbs light of all wavelengths except the red ones. And if you combine red and blue pigment, the mixture will absorb everything that either pigment absorbs. A pigment is a trap for particular wavelengths of light, so the more pigments you put in, the more light you catch and the less can get out.

So the physicist’s color wheel differs from the painter’s because light combines additively, while pigment combines subtractively. Except… this doesn’t make any sense! Yellow and blue paints make green, right? But if paints combine subtractively, yellow and blue should actually make… black. Here’s why.

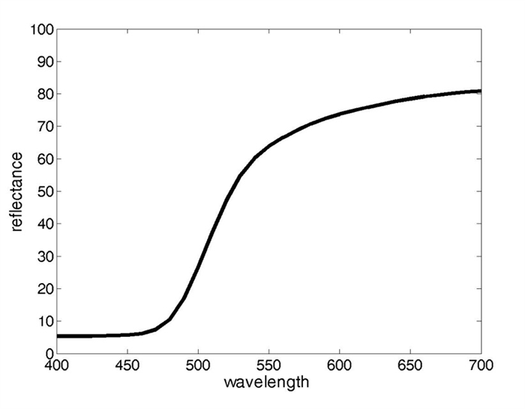

Blue pigment reflects blue light and absorbs red and green light. If you look at the physicist’s color wheel, you’ll see that red and green light combine to make yellow light:

So blue pigment reflects blue light and absorbs yellow light. Conversely, yellow pigment reflects yellow light and absorbs everything else – i.e. blue light. So blue pigment traps yellow light, yellow pigment traps blue light, and if you put the two traps together, you’ve caught all the light of the rainbow and made black!

And yet… I’ve been painting for years, and I can assure you: at least sometimes, blue and yellow do make green.

But how? Here are three reasons yellow and blue don’t always make black and sometimes make green, even though physics basically works.

1. Real-world pigments are impure.

Your typical tube of blue paint won’t perfectly absorb yellow light. Instead, it will reflect some light in the whole spectrum, and quite a lot of light in the green part of the spectrum in particular. So if you mix a pigment like this with a “cool” yellow – that is, a yellow that also reflects a fair bit in the green range of the spectrum, you’ll get a pigment that reflects quite a lot of green light. It will still be more muted than pure green, but it will be much closer to green than to black.

So your art teacher wasn’t lying to you: yellow and blue sometimes make green. Well, maybe they lied a little bit: you can’t actually make all the colors out of red, yellow, and blue. Certainly not if you only have one tube of each color. You can mix green from a cool blue and cool yellow, and orange from a warm yellow and warm red. But if you use the same tubes of yellow throughout, either your green or your orange are going to look quite a bit like brown.

2. Painters and physicists speak different dialects.

My Polish friends take offense when I call navy blue jeans “blue,” since “navy blue” is a separate Polish word. My partner keeps insisting that my blue shirt is “purple.” By what right was I assuming that my art teacher and the optics textbook meant the same things by “blue”?

In fact, as a painter, I’d call the physicist’s blue a warm blue, almost a purple. If I try mixing a paint of that precise shade of blue with a yellow, I’ll still get green, but a very impure one. So at least some of the disagreement between painters and physicists is terminological.

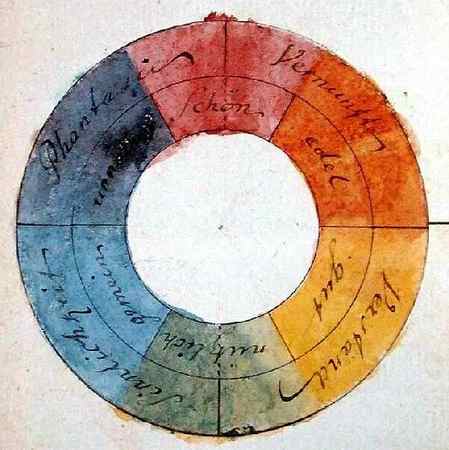

For the physicist, the true additive primaries are cyan, magenta, and yellow. Compare that to the most influential color wheel in art history, taken from Goethe.

If you forget about the names, Goethe’s color wheel is remarkably close to the physicist’s one. Goethe’s “red” is a cool red that is quite close to what a physicist might call “magenta;” his blue is a cool, almost turquoise cousin of “cyan.” (And his “purple” is basically the physicist’s blue.) Given the limitations of the pigments that were available in Goethe’s day, that’s really the closest you could expect him to get to the “true” subtractive primaries of yellow, magenta, and cyan.

So even if pigments combine subtractively, what the painters call “blue” and “yellow” does often combine to green. And now… time to knock down this whole house of cards. The final reason why yellow and blue don’t always make black (but do sometimes make grey):

3. Pigments don’t always combine subtractively.

What happens if you combine red and white paint? You get pink, right? But that’s not what physics tells us! White paint reflects (more or less) the full spectrum; it doesn’t trap any wavelengths. So (subtractively) mixing in white pigment shouldn’t do anything to red!

Here’s the secret: red and white make pink because most paints don’t actually combine subtractively. Instead, if you mix equal amounts of two perfectly opaque pigments, each ray of light will interact with particles from just one of the pigments. So in an opaque red/white mixture, about half of the light will interact with white pigment particles and be reflected back, and half will interact with red particles and be reflected only in the red spectrum (and absorbed in the green and blue spectrum). And that’s precisely what pink is: light with components in all wavelengths, but with more intensity in the red range.

This is so-called “additive-averaging mixing.” By contrast, if the pigment is transparent, light will pass into the paint mixture and bounce around inside it, interacting (and getting absorbed by) pigments of both colors. This gives our old friend, subtractive mixing. This is how your printer works: by combining thin, transparent layers of yellow, magenta, and cyan. It’s probably not a coincidence that Goethe’s color wheel was made with watercolor paints, which are quite transparent as well. It’s also possible to dilute oil paints and apply them in transparent glazes; if you do that, you can actually become a human printer and paint with a cyan, magenta, yellow palette!

There’s that old joke where a farmer asks a physicist for help increasing milk production. “I have the answer,” responds the physicist, “but it only works for a spherical cow in a vacuum.” Blue and yellow only make pure black when they are such spherical cows: fully transparent pigments which perfectly absorb all wavelengths except those determined by the physicist’s idiosyncratic dialect. Outside of textbook vacuums, blue and yellow make brown, grey, green, and everything in between.

If you’d like to learn how to mix colors in practice, I’m teaching a color-centered beginners’ painting course starting July 7th. You can learn more about it and sign up here. (The first session just passed, but please feel free to contact me if you’re interested; I might create a makeup session.) And if you’d like to get my essays in your inbox, you can sign up below.

Processing…

Success! You’re on the list.

Whoops! There was an error and we couldn’t process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.