This phenomenon occupied many scientists, including physicist James Clerk Maxwell, known for his work on electromagnetism. He conducted several experiments in which he dropped cats from various heights (including from open windows) and onto beds and tables. But it wasn’t until 1969 that the “falling cat problem” was solved. As it turned out, the cat’s body had not been considered carefully enough. It is not simply a cylindrical object that magically begins to spin. If you look closely, you can see that a cat’s upper and lower body rotate in opposite directions. Thus, conservation of angular momentum is preserved. If the animal rotates like a pepper mill in two different directions, the change in angular momentum is zero.

36 Best Cat Instagram Captions for Every Photo of Your Feline Friend

People who love cats really love them, and people who don’t like cats really don’t like them—there’s no in-between. As divisive as these creatures are, every cat lover understands why they make such amazing pets. Still, it’s not always easy to put into words why you’re so obsessed with your four-legged furball. (Cats are creatures of mystery, after all!) Because felines don’t have the same reputation as other universally adored animals (we’re looking at you, dogs) it’s important to represent them well. The best way to do that? With an adorable Instagram post of your cat, obviously. While you’re at it, check out our top picks of gifts for cat lovers.

First, capture a video of your sleepy kitten purring, or snap a shot of your crazy cat doing aerial stunts. Who could resist something so cute or funny?! After you’ve taken the perfect photo or Boomerang, it’s time to come up with a caption. Resist the urge to write an entire paragraph about why your cat is the greatest living being to grace the planet (they know it and you know it, and that’s enough). Instead, stick to a funny cat joke or cute quote that shows how much you love your kitty. Trust us, your followers will thank you. See below for the best cat Instagram captions to use when showing off your favorite feline!

Getty

- All you need is love and a cat.

- Not all angels have wings. Sometimes they have whiskers.

- Thanks fur the memories.

- The road to my heart is paved with paw prints.

- You’re the cat’s meow.

- Love is a four-legged word.

- Anything is paws-ible with a cat by your side.

- I love you meow and furever.

- Cats are not our whole lives, but they make our lives whole.

- You had me at meow.

- I want to spend all nine lives together.

- Home is where the cat is.

- If there are no cats in heaven, I don’t want to go.

- To me, you are purr-fect.

- I’m a smitten kitten.

- I love you more than you love catnip.

Funny Cat Captions

Getty

- Looking good, feline better.

- I have a cattitude problem.

- The more people I meet, the more I love my cat.

- Cat hair, don’t care.

- Yes, I am a crazy cat lady. What’s your point?

- The cat is in charge, I just pay the rent.

- Sorry I’m late. My cat was sitting on me.

- All visitors must be approved by the cat.

- I cat even.

- She came, she purred, she conquered.

- Are you kitten me?

- Boys? Whatever. Cats? Forever.

Cat Quotes for Instagram Captions

Getty

- “What greater gift than the love of a cat.” — Charles Dickens

- “There are two means of refuge from the miseries of life: music and cats.” — Albert Schweitzer

- “It is impossible to keep a straight face in the presence of one or more kittens.” — Cynthia E. Varnado

- “No home is complete without the pitter patter of kitty feet.” — Unknown

- “As every cat owner knows, nobody owns a cat.” — Ellen Perry Berkeley

- “If cats could talk, they wouldn’t.” — Nan Porter

- “There are few things in life more heartwarming than to be welcomed by a cat.” — Tay Hohoff

- “People who don’t like cats were probably mice in an earlier life.” — Unknown

Senior Editor

Kelly O’Sullivan is the senior editor for The Pioneer Woman and manages the website’s social channels, in addition to overseeing content strategy and news.

How High Can Cats Fall and Survive?

The laws of physics state that the higher the fall, the harder the impact. But a study from the 1980s paints a different picture—at least for cats. Two New York City veterinarians described a total of 132 cases between June and November 1984 in which cats had fallen from as high as the 32nd floor of high-rise buildings. Overall, 90 percent of the cats survived. When the veterinarians documented the injuries, they made an astonishing observation: while the severity of the damage increased up to a height of about seven stories, it seemed to decrease thereafter. In other words, a fall from the 11th floor could end more gently for a cat than one from the sixth floor.

Once again, the felines seemed to break the laws of physics. The higher the floor from which a body falls, the longer it is accelerated by Earth’s gravity. Thus, its speed should increase more and more until it finally hits the ground. The abrupt impact converts the animal’s kinetic energy from falling into other forms of energy, which can lead to broken bones, collapsed lungs, and worse. Thus, falling from high floors should have more unpleasant consequences than from low floors.

But this way of thinking about the feline free-fall ignores air resistance. After all, cats do not fall to the ground in a vacuum but move through air that can slow their fall. Thus, two opposing forces act on a cat during a fall: the gravitational force Fg and the frictional force FR, which slows it down. While Fg has a very simple form and is merely the product of the mass m of the cat and the acceleration caused by gravity g, the air resistance depends on the cross-sectional area A, the drag coefficient cW, the air density ρ and the velocity v of the falling object: FR = ½ x ρ x A x cW x v 2 . At the beginning of the fall, the cat has a velocity of zero, so only the acceleration caused by gravity acts on it, but as v increases, the opposite frictional force then makes itself felt. Thus, to determine the concrete motion of the animal, one must calculate the total force (Fg – FR). This then determines which acceleration acts on a cat of a certain weight m: m x a = Fg – FR.

A Speed Limit for Falling Felines

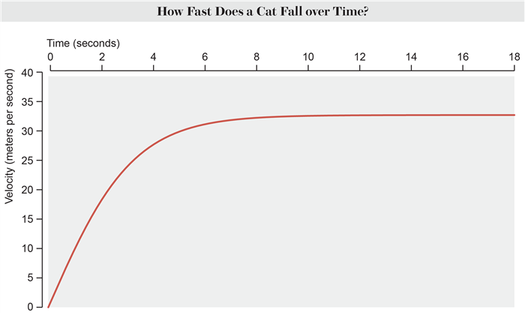

The acceleration corresponds to the change in velocity, which can be expressed mathematically by a derivative, a = d ⁄dt v. So if you want to calculate the speed of the cat at a certain time, you have to solve a complicated system of equations containing both the speed itself and its derivative (acceleration): m x d ⁄dtv = m x g −½ x ρ x A x cW x v 2 . For such differential equations, there is often no exact solution. In this case, it is possible to calculate a solution for the velocity corresponding to a hyperbolic tangent. Depending on the cross-section and weight of the cat, you end up with a curve that grows rapidly at the beginning and then flattens out and converges to a constant value: the animal gains speed quickly at the beginning of the fall before the air resistance eventually becomes so strong that it no longer speeds up, as physicist Rhett Allain of Southeastern Louisiana University calculated for Wired.

You can also calculate this terminal velocity, or upper speed limit, quite easily. Because the terminal velocity results when the frictional force is exactly as large as the gravitational force in this case, the two forces cancel each other out and a falling object plummets towards the ground with constant velocity. So you just have to solve the equation m x g = ½ ρ A cW v 2 for v, and you get: v = √( 2mg ⁄ρAc).

To give a specific value for the terminal velocity of a cat, one need only insert numerical values for the variables. While one can estimate the weight and cross-sectional area of a cat, the drag coefficient is more difficult to determine. Suppose a cat weighs 4 kilograms (about 8.8 pounds), is 50 centimeters (around 19 inches) long and 15 centimeters (nearly 6 inches) wide. These measurements would give the animal a cross-sectional area of A = 0.075 square meters. The cat could also have the drag coefficient of a cylinder (cW = 0.8). Then the final speed of the animal is: v = 32.68 meters per second, which corresponds to just under 120 kilometers (or 74.5 miles) per hour.

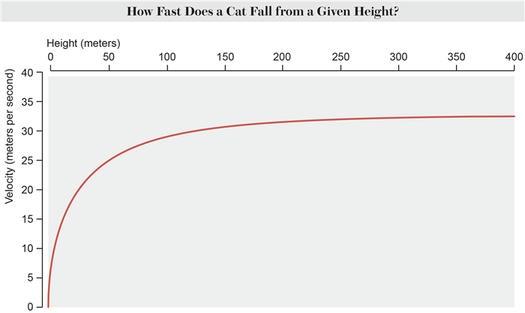

To find out at what height a cat reaches this terminal velocity, one can solve the differential equation and thus calculate the velocity at the time of impact as a function of the height of the fall.

As can be seen from the graph, cats already reach a speed of 30 meters per second at a fall height of 100 meters. Because cats have already been observed to survive falls from higher buildings (such as from the 32nd floor), they can theoretically survive an impact with the greatest possible terminal velocity of 120 kilometers per hour. Consequently, the animals could, in theory, survive a fall from any conceivable height.

Actual Effect or Survivorship Bias?

But this terminal velocity calculation does not explain the observations of the New York veterinarians: Why do cats seem to survive a fall from the seventh floor or higher better than from lower floors? One explanation involves the animals’ experience.

When a cat falls from a low height, it is weightless for a short time. Instinctively, therefore, it will extend its legs underneath it to land on all fours. At high fall heights, however, this strategy is not useful: aligned legs can lead to serious injury because the animal’s weight is distributed awkwardly. This difference may explain why the survival rate decreases with increasing height—at least up to the seventh floor. But at greater fall heights, the frictional force becomes noticeable during the fall. That’s why, the veterinarians speculate, the cat no longer has the sensation of falling. Thus, it can relax and will not stretch its legs. It lands more gently, with a more even weight distribution and, therefore, better chances of survival.

But there is also a simpler explanation for the observation—albeit a more depressing one for animal lovers. The veterinarians’ findings could reflect the so-called survivorship bias. If a cat falls from a high floor and dies instantly, the owner probably won’t bother to stop by a veterinary clinic. Therefore, the number of unreported deaths is probably higher than what has been recorded by medical professionals.

This article originally appeared in Spektrum der Wissenschaft and was reproduced with permission.