Download Free PDF View PDF

The Interiority of Landscape: Transcendence in a Late-Ming Painting of Snowy Mountains

This article argues that late-Ming-era landscape paintings can be understood best historically in the context of such cultural practices as Daoist visualization and the discourses that accompanied it. Taking a Snowy Mountains-themed painting, it critiques the Cartesian perspective by demonstrating that landscape paintings were not regarded as closed objects available to the thinking subject for mere aesthetic appreciation. Instead, they were thought to possess an interiority that afforded space for the human spirit to roam in. A certain teleology associated with this practice was the merging of the beholder’s human body with that of a purported broader cosmic body, thereby also giving interiority to the physical world-including landscape. Access to this space, or, “entering the mountains,” allowed for a momentary yet reproducible experience of transcendence. To make this argument, the article draws upon late-imperial narrative prose, Daoist texts, and other materials from the same period, all describing the cultural significance of this pattern of interiority, accessibility, visualization, and merging of bodies.

See Full PDF

See Full PDF

Related Papers

East Asian History

ABSTRACT: From the 18th century onward, “Western” elements including receding perspective, cast shadows, and European architecture began to appear in north-Chinese temple- and opera stage-murals. This paper presents a case study of painting traditions in a single county in rural northern Hebei. I begin with a sketch history of the physical and visual cultures of this county between 1500 and 1949, arguing that the open squares between temples and opera stages formed the main public spaces of rural life and the main points of contact with the modernizing world. I trace a pair of interlinked “Western” themes through opera stage murals, showing how the stories and buildings depicted in these scenes represent a unique record of the rural Chinese imaginary and its contact with the wider world. I then return to temple painting, arguing that “Western” techniques on both stage and temple walls were used to create access points to ontologically “other” spaces, either holy, fictional, or foreign. I conclude with close readings of a few individual murals from this period, suggesting that these obscure village paintings represent a forgotten renaissance of artistic production in the early-modern countryside. Academic confessions: I should have cited James Flath, “The Cult of Happiness” and Judith Zeitlin, “Historian of the Strange”. By the time I realized this, however, the article was already in the final stages of print.

Download Free PDF View PDF

“In this dissertation, interdisciplinary research demonstrates how Chinese people affiliated with different religions and ideologies of the Song period (960- 1279 CE) utilized artistic, literary and visual representations to merge the natural world with the human body. This fusion of natural and human worlds in representation appears in a variety of contexts, including paintings of famous Song landscape artists, writings of literati thinkers, architectural developments of Neo- Confucian scholars, body charts recorded in the Daoist Canon, and artwork connected to Chinese Buddhism. Traditionally, scholarship within the field of religious studies relies heavily upon textual sources, and material objects are often seen as accessory to the findings related to these sources. When found within the context of religion, art objects are in this same vein often described as representational as opposed to foundational of religious experience or its aspects. This thesis asserts that Song Chinese people used art and other material objects not only for the purpose of representing the world in which they lived, but also as a means of expressing, developing and empowering their religions and ideologies. So powerful were these material representations, in fact, that in certain cases they may have acted as a primary conduit through which the religion was experienced. As the dissertation will show, the interaction between the non-material activity of visualization, or how people create images in their minds, and representation, or how people create material objects to reify the images in their minds, is often pivotal, as opposed to accessory, to some of the later ideological developments of the Chinese people. This thesis also examines sacred space of the Song period, theorizing that an important spatial synergy took place between physical representations and the religions of medieval China: images had become intertwined with how different groups of people visualized their bodies, as well as how these groups represented a human relationship at work with the natural world. In essence, Song representations of mountains, landscape and other natural formations act as material records of how people visualized their own bodies in microcosmic and macrocosmic form.”

Download Free PDF View PDF

The Boolean Journal

Download Free PDF View PDF

Journal of Daoist Studies

A Thousand Miles of Streams and Mountains (Qianli jiangshan tu 千里江山圖) is the name of a famous 12-meter-long landscape painting of the Northern Song dynasty. It was painted in 1113 by a 17-year-old prodigy, Wang Ximeng 王希孟, under Emperor Huizong’s 徽宗 (r. 1101-1125) supervision, an accomplished painter and a Daoist initiate himself. In this paper I argue that the handscroll depicts a story of Daoist self-cultivation, from lay-life, initiation, receiving training, to eventually attaining Dao (becoming immortal) and the afterlife as an immortal. This story is depicted in both the iconographic details of the figures, buildings, paths, bridges and other elements, guiding the viewer through the landscape, and the composition of the handscroll, mirroring the development of the story by means of the particular placement and the form of the landscape. Because of his close involvement, the landscape painting offers a unique and amazing insight into Huizong’s personal views on what constitutes a Daoist and Daoist selfcultivation, if not his ideas on Daoist landscape painting in the Song dynasty.

Download Free PDF View PDF

Asiatische Studien – Études Asiatiques

This paper attempts to delineate the relation of early Chinese views on vision and visuality to nascent reflections on painting arising in the Early Medieval period. Ever since that time, pictorial creativity has been associated with Buddhist ideas of spiritual perfection. Likewise, the Early Medieval concern for the visualization of spiritual journeys to exceptional humans (and superhumans) through imaginary landscapes seems to be of Buddhist origin. The first part of this paper gives a short sketch of the intellectual landscape in which theorizing on painting since the 5th century CE first arose. The main body of the study, consisting of parts two through five, close readings of pre-Buddhist texts on vision and imagination. From these exploratory investigations it emerges that the very terms that are key in early reflections on painting such as ‘spirit’ (shen 神), ‘perspicacity’ (ming 明), but also ‘imagination’ (xiang 想) and ‘symbol’ (xiang 象) are closely related to a specific conc.

Download Free PDF View PDF

Asiatische Studien – Études Asiatiques

This essay examines a number of statements on painting and visual perception by Chinese literati artists of the late Mingearly Qing periods. It argues that the approaches to pictorial representation and creativity entailed in these statements reveal a considerable impact of Buddhist theories of consciousness. In the theories analyzed, pictorial representation is discussed in terms of ways and modes of how the mind relates to the world. As will be demonstrated, the function of expressing cognitive organization in representation is given more prominence than the function of rendering an external reality. The view of pictorial representation as being essentially what the mind produces in its relation to the world provides a basis for the assumption of a fundamental affinity between the creation of an image and the process how phenomenal reality unfolds by virtue of cognitive operations. This assumption seems to broadly underpin the painting theories discussed. And it is this assumption that provides a clue how and why the literati artists adopt Buddhist theories of cognition to the understanding of art. In the last section of the essay, we turn to the sources which cast still another perspective on artistic practice, namely a practice which captures a single moment of pure direct perception.

Download Free PDF View PDF

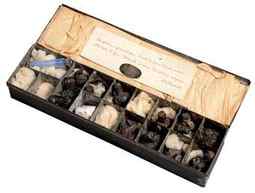

Constable’s techniques, materials and ‘six footer’ paintings

As John Constable’s professional ambitions increased, so did the size of his canvases. Many of his earlier paintings are small as he painted out-of-doors and the canvases needed to be small enough to carry around. But in around 1819 he began to paint on a much larger scale, and through the 1820s he produced a sequence of six-foot paintings – or ‘six-footers’, of which Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831 was the last. Perhaps part of the reason he painted these huge paintings was to help them stand out at crowded Royal Academy exhibitions. But also, by painting such vast canvases, Constable was asserting his belief in the importance of landscape, then generally considered an inferior form of art.

The paintings all depict incidents in the working life of the River Stour, usually shown at noon. The White Horse 1819, (the first of the ‘six-footers’) shows a horse being ferried across the river. It was a critical success and Constable was voted an Associate of the Royal Academy on the strength of it. The Hay Wain 1821, with its focus on the hay cart under dense clusters of clouds, evokes a specific midday moment as the vehicle turns towards the distant fields.

Preparatory sketches

In preparation for these monumental six-footers Constable made full-size preliminary sketches in oil paint. These helped him to work out his composition and ideas before tackling the final canvas. This unique practice is unprecedented in the history of Western art, and one that has shown him to be distinctly ‘modern’ in his approach. Today these full-scale sketches are admired just as much as the final exhibition pieces.

The full-scale compositional sketch for Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows would have been built up from several sketches and paintings made of the cathedral from different views. Significantly it does not include a rainbow, a key iconographical detail that Constable incorporated while working up the final piece.

Left Right

Technique and application of paint

At the time Constable was working, the surface of a painting was expected to be refined and smooth, with brushstrokes as invisible as possible. But Constable wanted to create a range of marks, surfaces and textures to reflect the textures that he saw in nature and to add to the mood of the painting. He used a palette knife and brushes to create these expressive surfaces which are surprisingly varied: in some areas the paint is thick and craggy and in other places it is fluid and thin. Constable also added small smatterings of white paint to the surfaces of his paintings to suggest the flickering light across the landscape and its reflection off the surface of the water.

Constable’s lively mark-making contributes to the powerful impact of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 1831. Take a closer look at the surface of the painting and discover some fascinating insights into Constable’s techniques and materials from Tate’s conservation specialists:

This is one of the surviving palettes. It is covered with remains of colours such as vermilion, emerald green, chrome yellow, cobalt blue, lead white and madder, ground in a variety of mediums such as linseed oil mixed with pine resin. These can all be found on the surfaces of Constable’s later works, as translucent ‘glazes’ and crisp highlights.

His metal paint box of c.1837 is divided into seventeen compartments. It contains a cork-stopped glass phial with blue pigment, a lump of white gypsum probably used for a variety of purposes including drawing and roughening paper.

The paint box also contains various paint bladders with the artist’s own or commercial ready-mixed paint. (Today oil paint is usually squeezed out of metal tubes, but these were only invented in the mid nineteenth century. When Constable was painting, paint bladders would have been used to store and carry oil paint. The bladders were made from pig membrane and tied at the top with strong twine to stop air from getting to the paint and drying it).

This mix of newly developed materials with more traditional ones that he prepared himself, meant that he was able to achieve very exact effects of colour and texture. He also used poppy oil to mix his pigments. As this was a slow-drying medium it allowed him to rework the surfaces of his paintings again and again over an longer period of time, before the paint dried.