In 1889, inspired by a famous astronomical drawing that had been circulating in Europe for four decades, Vincent van Gogh (March 30, 1853–July 29, 1890) painted his iconic masterpiece “The Starry Night,” one of the most recognized and reproduced images in the history of art. At the peak of his lifelong struggle with mental illness, he created the legendary painting while staying at the mental asylum into which he had voluntarily checked himself after mutilating his own ear.

Van Gogh’s method of painting Starry Night

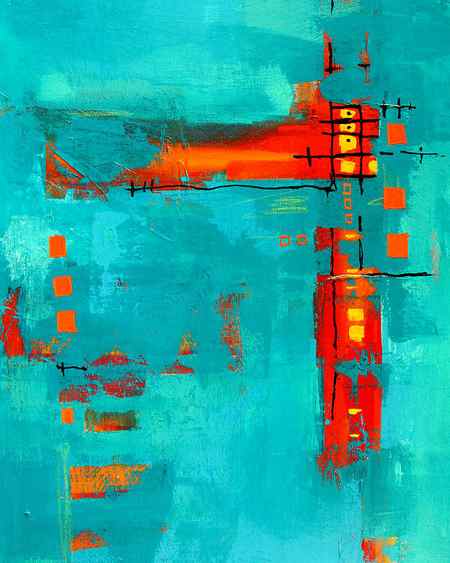

Each artist’s paintings are a reflection of the world: Degas saw the world in pastel colours, Signac depicted it as mottled, and Leonardo da Vinci saw it as ‘ethereal’. All the great artists painted their masterpieces not with paints, but with emotions. Today, we are going to talk about one of the most unusual techniques of all: impasto.

The history of impasto

Impasto is an Italian term and it translates as ‘smooth’ or ‘paste-like’. The technique involves giving the paints a thick consistency with the help of a palette knife, brush or spatula. The brushwork will retain its uneven texture. There are a large number of visual effects that an artist using the technique may be striving to achieve, but the most important ones are the added bulk and the play of light and shade. The brush-strokes may be straight, rounded or cross-hatched. Some artists only used this approach for certain elements of their works, with the aim of emphasizing them and bringing them to the fore, while others covered the whole canvas with an uneven ripple effect.

Vincent van Gogh “The Starry Night”

The impasto technique is usually associated with the work of Vincent Van Gogh. It is said that he applied the paints directly onto the canvas and simply mixed them together with his own fingers. One of the examples of the impasto technique in his oeuvre is the painting The Starry Night. Here, in order to make the stars in the night sky appear as bright as possible, he strove to apply paint with an extremely thick consistency, using bold brush-strokes, thereby highlighting the lights.

In order for the brush-strokes to appear even thicker and more expressive, artists did not shy away from using thickening agents on occasion. This would lend the painting an incredible texture. One of the substances widely used for this purpose, for instance, was wax. With each brush-stroke, the touches of the palette knife or spatula were imprinted on the painting. Works featuring this technique were produced by artists from a wide range of movements and eras: the Renaissance, the Baroque period, Impressionism, Expressionism, Post-Impressionism. Interestingly, the Impressionists applied paste from tubes directly onto the canvas, creating the outlines required with a brush once the paint was in situ.

The 3D effect and optical illusions

Rembrandt and Velazquez were among the other great painters to have used this method of applying paint extensively when creating their famous works. Surprisingly, they were able to use impasto to create naturalistic textures: gemstones, small wrinkles on people’s faces, the flowing locks of beautiful noblewomen, lace ribbons, the folds of garments and fabrics, the gleaming sparkle of adornments and the glint of jewellery, atmospheric phenomena and effects: all the details that might at first glance be deemed insignificant were portrayed with amazing subtlety and sensitivity.

Rembrandt van Rijn “Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar”

In the era of Impressionism and Expressionism, this technique made it possible to obtain a wonderful mirror-image of a crumpled or broken surface, to pick out areas of light amid the darkness, and to emphasize a space. It was the perfect way to convey feelings, concerns and emotions for the paintings of the Expressionists, for them to express their egos on canvas, and to show what is accessible only to those who see, not to those who merely look. Claude Monet, for example, used an architectural approach to the impasto technique, at a time when other Impressionists were applying two methods simultaneously: they were using materials that helped with setting and devising new bases for their paints. Edgar Degas was an exponent of the first of these techniques, incidentally.

Obtaining the textures required

When acryl is used, there is a wider range of possibilities in terms of the bases that can be created, but primers like this are deemed to be too coarse to withstand cracking and peeling. That said, despite its drawbacks, it can really add zest to an artist’s work. Whereas in the past artists strove to avoid having brush-strokes visible on their canvases, today the reverse is true: there are quite a number who use bold, tangible brush-strokes to give the required character to an element of the painting.

There are a whole range of methods and rules for applying paints to bases:

- With the help of a brush, a palette knife, a tube or using additional additives;

- The thick layer should be allowed to dry in conditions whereby the process can take place as slowly as possible. This approach protects the layer of pigment from cracking up and prevents wrinkles from appearing;

- If the ingredients are too fatty, this will definitely make it more difficult to create textures and expressive brush-strokes;

- Flat brushes or small brushes made of artificial horsehair will be ideal for this technique;

- If you add sawdust, sand or very fine grit to the pigment, this will lend a unique aspect to the texture and allow you to really liven up your work, and above all – to increase the volume of each brush-stroke;

Some artists cover their completed paintings with a special glaze. Its thin film provides excellent protection that will prevent cracks and wrinkles appearing in the pigment and prevent it from peeling.

The most popular ways of using impasto:

Needless to say, this technique can be used in some unbelievably diverse ways. And yet after so many centuries of variation, there is still enough room to let your imagination run wild. Nonetheless, there are a few techniques which are already thought of as classic ones:

- The thick stain: the paint is applied in broad, generous brush-strokes, as if you were spreading peanut butter on a piece of toast. The marks made by the palette knife will remain visible, and they will provide texture to the area in which they are applied;

- Dashed and dotted lines: this effect is achieved when the paint is dabbed onto the canvas with a palette knife. On the lower part of the canvas, the paint that is applied gets ever so slightly stretched when the implement is pulled away from the canvas, leaving tiny crests;

- Rounded brush-strokes: a rounded brush and a very moist pigment are used to create the arcs and semi-circles that Van Gogh loved to paint;

- Lines: it is important that the lines don’t overlap with one another. This will provide extra character to the part of the canvas on which it is used;

Using whatever materials come to hand: this is not exactly a classic technique. Pick up anything that can be used to spread the paint over the canvas and simply experiment. You could start with a little cushion brush, for instance – you’re bound to get unusual results.

The impact of impasto is such that it is worth being bold and adopting a free style; use curved, sweeping brush-strokes to apply a thick layer of paint to the canvas and show the whole world how it looks, when seen through your eyes!

The Technique

One of the most striking aspects of Starry Night Over the Rhone is its technique. Van Gogh used thick, impasto brushstrokes to create a vivid, textured surface that captures the essence of the night sky. The colors he used are also remarkable, with a rich palette of blues, greens, and golds that blend together to create a sense of movement and depth.

Another interesting technique that Van Gogh used in this painting is the concept of light. By using light as a subject in itself, he was able to convey a sense of emotion and mood. The stars, for example, are painted in a way that makes them appear to be twinkling and dancing, while the reflections on the water give a sense of movement and life.

The Themes

While the technique of Starry Night Over the Rhone is impressive, its themes are just as important. One of the key themes of this painting is the relationship between man and nature. The river, sky, and stars all come together to create a beautiful and harmonious scene, one that speaks to the power and majesty of the natural world.

Another important theme in this painting is the idea of hope. Despite the dark and mysterious nature of the night sky, there is a sense of optimism and wonder that shines through. The stars, in particular, seem to represent the hope and dreams of humanity, twinkling in the darkness and lighting the way forward.

Facts About This Masterpiece

- “Starry Night Over the Rhone” was included in the 1889 Society des Independents exhibition in Paris, and was one of only a few Van Gogh works that were publicly displayed before his death.

- Unlike Starry Night and Café Terrace at Night, “Starry Night Over the Rhone” misplaced the Big Bear constellation in the sky.

- In Arles, the gas lights and their reflections in the river were a new phenomena. Paris had only been illuminated at night since roughly 1853.

- The thick brush strokes and texture in the work were described as “ferocious impasto” by critic Georges Lecomte, a contemporary of Van Gogh.

- The locations where Van Gogh set up his easel to paint plein air are now part of the Arles Van Gogh Tour.

- In “Starry Night Over the Rhone,” Van Gogh emphasizes the brightness of the lights, implying their harshness in the natural landscape, by using the complementary hues blue and yellow.

- Of terms of warmth, the blue and yellow tones in the artwork complement each other. Van Gogh effectively communicates how the heat of the lights sears on the chilly water by juxtaposing yellow and blue.

You Might Also Like

Beauty In Ignorance: 11 Sunflower Painting By Vincent Van Gogh

February 10, 2023

Warm color and cool color- The Great Wave off Kanagawa

March 21, 2022

10 facts about The Scream that you should know

January 25, 2023

Our primary aim is to provides a platform for children & adults to explore the world of Visual Art & Culture. We have opened our offline classes at HSR Layout & online Art classes are structured based on age group – 5to7yrs, 8-13yrs and adults. Registration classes are open. We follow strict Covid-19 protocol. Offline class ratio is 1:5 students. reach us for more information.

Quick Links

- Home

- About us | Art classes in HSR Layout

- Our Services

- Art Studio

- Blogs

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and conditions

Art classes

- sitemap

- Art Course

- Art Studio

- Online Art Class for 5-7yrs

- Online Art class for 8-13yrs

- Adults Art classes

see more

Van Gogh and Mental Illness

The Secret Museum: Van Gogh’s Never-Before-Seen Sketchbooks

Vincent van Gogh on Art and the Power of Love in Letters to His Brother

Labors of Love

Famous Writers’ Sleep Habits vs. Literary Productivity, Visualized

7 Life-Learnings from 7 Years of Brain Pickings, Illustrated

Anaïs Nin on Love, Hand-Lettered by Debbie Millman

Anaïs Nin on Real Love, Illustrated by Debbie Millman

Susan Sontag on Love: Illustrated Diary Excerpts

Susan Sontag on Art: Illustrated Diary Excerpts

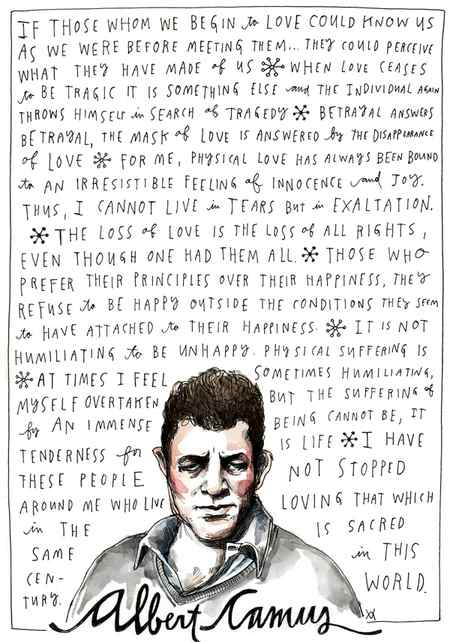

Albert Camus on Happiness and Love, Illustrated by Wendy MacNaughton

The Holstee Manifesto

The Silent Music of the Mind: Remembering Oliver Sacks

The Fluid Dynamics of “The Starry Night”: How Vincent Van Gogh’s Masterpiece Explains the Scientific Mysteries of Movement and Light

In 1889, inspired by a famous astronomical drawing that had been circulating in Europe for four decades, Vincent van Gogh (March 30, 1853–July 29, 1890) painted his iconic masterpiece “The Starry Night,” one of the most recognized and reproduced images in the history of art. At the peak of his lifelong struggle with mental illness, he created the legendary painting while staying at the mental asylum into which he had voluntarily checked himself after mutilating his own ear.

But more than a masterwork of art, Van Gogh’s painting turns out to hold astounding clues to understanding some of the most mysterious workings of science.

This fascinating short animation from TED-Ed and Natalya St. Clair, author of The Art of Mental Calculation, explores how “The Starry Night” sheds light on the concept of turbulent flow in fluid dynamics, one of the most complex ideas to explain mathematically and among the hardest for the human mind to grasp. From why the brain’s perception of light and motion makes us see Impressionist works as flickering, to how a Russian mathematician’s theory explains Jupiter’s bright red spot, to what the Hubble Space Telescope has to do with Van Gogh’s psychotic episodes, this mind-bending tour de force ties art, science, and mental health together through the astonishing interplay between physical and psychic turbulence.

Van Gogh and other Impressionists represented light in a different way than their predecessors, seeming to capture its motion, for instance, across sun-dappled waters, or here in star light that twinkles and melts through milky waves of blue night sky.

The effect is caused by luminance, the intensity of the light in the colors on the canvas. The more primitive part of our visual cortex — which sees light contrast and motion, but not color — will blend two differently colored areas together if they have the same luminance. But our brains primate subdivision will see the contrasting colors without blending. With these two interpretations happening at once, the light in many Impressionist works seems to pulse, flicker and radiate oddly.

That’s how this and other Impressionist works use quickly executed prominent brushstrokes to capture something strikingly real about how light moves.

Sixty years later, Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov furthered our mathematical understanding of turbulence when he proposed that energy in a turbulent fluid at length R varies in proportion to the five-thirds power of R. Experimental measurements show Kolmogorov was remarkably close to the way turbulent flow works, although a complete description of turbulence remains one of the unsolved problems in physics.

A turbulent flow is self-similar if there is an energy cascade — in other words, big eddies transfer their energy to smaller eddies, which do likewise at other scales. Examples of this include Jupiter’s great red spot, cloud formations and interstellar dust particles.

In 2004, using the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists saw the eddies of a distant cloud of dust and gas around a star, and it reminded them of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” This motivated scientists from Mexico, Spain, and England to study the luminance in Van Gogh’s paintings in detail. They discovered that there is a distinct pattern of turbulent fluid structures close to Kolmogorov’s equation hidden in many of Van Gogh’s paintings.

The researchers digitized the paintings, and measured how brightness varies between any two pixels. From the curves measured for pixel separations, they concluded that paintings from Van Gogh’s period of psychotic agitation behave remarkably similar to fluid turbulence. His self-portrait with a pipe, from a calmer period in Van Gogh’s life, showed no sign of this correspondence. And neither did other artists’ work that seemed equally turbulent at first glance, like Munch’s ‘The Scream.”

While it’s too easy to say Van Gogh’s turbulent genius enabled him to depict turbulence, it’s also far too difficult to accurately express the rousing beauty of the fact that in a period of intense suffering, Van Gogh was somehow able to perceive and represent one of the most supremely difficult concepts nature has ever brought before mankind, and to unite his unique mind’s eye with the deepest mysteries of movement, fluid and light.

Complement with Van Gogh on art and the power of love and a peek inside his never-before-revealed sketchbooks.