When it comes to unique craft workshops, The Sage Artelier is your one-stop studio offering a variety of uncommon art jamming sessions. 2 of their most interesting ones include a LED Light Painting Workshop and Glass Painting Workshop.

18 Art Jamming Studios In Singapore For All The Art Lovers & Creative Souls Out There

We all love a good art jamming session. After all, it’s not just a chill time to bond with friends and family; it’s also therapeutic to smear paint on canvas.

But you don’t always need just paintbrushes to express yourself. If you’re seeking true creative freedom, then any medium could be a canvas for your next masterpiece. So we’ve sussed out the weird and the wacky, as well as the ol’ school and traditional ways to unleash your inner Picassso through these art jamming studios .

P.S. Advance booking is required for all studios.

Table of Contents

- Art jamming studios

- 1. The Art Nooq – Turn macarons into works of art

- 2. Avant-Garde Art Space – Assemble & decorate a ukulele

- 3. State of Shiok – Be a “tattoo artist” for a day

- 4. Sage Artelier – LED neon signs & pretty glass displays

- 5. Heaven Spot – Spray paint walls

- 6. Art Pop! – Destress with balloon splatter art

- 7. Room To Imagine – Design your own clocks with acrylic pouring

- 8. L’Atelier Du Rêve – Customise BE@RBRIKE-like figurines

- 9. Motion Art Space – Paint with a pendulum

- 10. Café de Paris – Paint in a cafe

- 11. Splat Paint House – UV art jamming in the dark

- 12. Wildflower Studio – Guided painting with cats

- 13. Boulevart – Family art jamming sessions

- 14. Heartroom Gallery – Art jam for only $38/session

- 15. My Art Space – Waterfront studio with free flow tea

- 16. Arteastiq – Free beverages & daily promos for sessions

- 17. Artify Studio – Flexible 2.5 hour art jamming

- 18. Paintblush – Art jam while sipping wine

- Bonus: Streaks n Strokes – Home kit & free online painting classes

1. The Art Nooq – Turn macarons into works of art

Food can be works of art, and no, we don’t just mean tiny portions on large plates that make good pics for the ‘Gram. At The Art Nooq , artists and foodies can combine their passions by painting on macarons to make them extra atas .

Image credit: @artnooq via Instagram

It’s a delicate job having to paint fine details on something this fragile. Rest assured, the art jam is guided by professionals, so your French pastries will look good enough to hang in The Louvre.

You’ll get 5 macarons to paint during the 2-hour session. The paints are edible too, so you can pop them into your mouth once you’re done snapping pics.

Price: $60/pax

ADMISSION FEE

$60/pax

ADDRESS

195 Pearl’s Hill Terrace, #01-58, Singapore 168976

Opening Hours: Friday Off Show Time HideCONTACT INFORMATION

RECOMMENDED TICKETS AT S$35.00Cheapest S$35.00

2. Avant-Garde Art Space – Assemble & decorate a ukulele

Musicians – aspiring or otherwise – here’s how you can walk away with a new skill and instrument from an art jam session. Avant-Garde Art Space has a Ukulele Paint & Play Workshop that lets you assemble while customising your own ukulele.

Image credit: @avantgardeartspace via Instagram

Paint and assembly takes place within a 3-hour-long session . That’s plenty of time to get acquainted with your new instrument, like learning its anatomy and how strings can be changed in the future.

Once complete, the workshop ends with a lesson on basic playing techniques, so you can start jamming immediately.

Avant-Garde Art Space

ADMISSION FEE

$108/pax

ADDRESS

39 Jln Pemimpin, #04-03A Tailee Industrial Building, Singapore 577182

Opening Hours: Show Time HideGOOGLE REVIEWS

CONTACT INFORMATION

Understanding Functional Art

Functional art is a unique genre of art that combines both aesthetics and utility. It is a form of art that serves a practical purpose while still being visually appealing.

In this section, we will explore in more detail what functional art is and what makes it different from other forms of art.

Defining Functional Art

Functional art is a term used to describe art objects that serve a utilitarian purpose while also being aesthetically pleasing.

What makes functional art stand out is its focus on both aesthetics and utility. These pieces are not just meant to be admired from afar but are meant to be used and enjoyed. Whether it’s a chair that doubles as a sculpture or a lamp that illuminates a room while also serving as a conversation piece, functional art adds an element of creativity and innovation to everyday objects. It challenges the traditional notion of what art should be and expands the definition of what can be considered art.

Function is a crucial aspect of functional art. The object must serve a purpose beyond just being visually appealing. The design of the object must consider the intended use and functionality, and the aesthetics of the object must complement its function.

Art is another essential aspect of functional art. The object must be visually appealing and well-crafted. The design must be unique and creative, and the object must evoke emotion or thought in the viewer.

Functional art is also known as utilitarian art. The term utilitarian refers to the object’s usefulness in everyday life, while the term art refers to the object’s aesthetic qualities.

In summary, functional art is a unique genre of art that combines both form and function. It is a form of art that serves a practical purpose while still being visually appealing. The design of the object must consider both its intended use and aesthetics, and the object must be well-crafted and evoke emotion or thought in the viewer.

Historical Overview of Functional Art

Functional art has been around for centuries and has played an important role in shaping the way we live. From the ancient Chinese vases to the modern-day furniture, functional art has been an integral part of our daily lives. In this section, we will take a look at the history of functional art and how it has evolved over the years.

Bauhaus and Functional Art

By Spyrosdrakopoulos – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38946836

One of the most significant events in the history of functional art was the establishment of the Bauhaus school by Walter Gropius in 1919. The Bauhaus school was a revolutionary institution that aimed to combine art and technology to create functional objects that were aesthetically pleasing. The school brought together artists, designers, and craftsmen to work together in a collaborative environment. The Bauhaus school had a significant influence on the development of functional art and design, and its legacy can still be seen today.

The Bauhaus school’s philosophy was based on the idea that form follows function, and this idea was reflected in the school’s approach to design. The school’s focus was on creating functional objects that were simple, elegant, and affordable. The Bauhaus school’s approach to design had a significant impact on the development of modernist design and functional art.

In the 1930s, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition of Bauhaus design, which helped to popularize the school’s philosophy and approach to design. The exhibition showcased the school’s innovative approach to design and its emphasis on functionality and simplicity.

In conclusion, the Bauhaus school played a significant role in the development of functional art and design. Its philosophy of form follows function has had a lasting impact on the design world, and its legacy can still be seen today.

Functional Art in Furniture

When it comes to functional art, furniture is a great place to start. Furniture pieces can be both aesthetically pleasing and practical, making them the perfect embodiment of functional art. Here are some sub-sections to explore:

Chairs and Tables

Chairs and tables are some of the most common furniture pieces that can be turned into functional art. With a little bit of creativity and innovation, chairs and tables can be transformed into unique, one-of-a-kind pieces that are not only functional but also visually appealing. Materials such as wood, glass, and concrete can be used to create functional art chairs and tables that are both sturdy and beautiful.

Sofas and Beds

Sofas and beds are another great example of functional art in furniture. These pieces can be designed to be both comfortable and visually stunning. A functional art sofa can be created with unique shapes, patterns, and materials to make it stand out in any room. Similarly, a functional art bed can be designed with intricate details and materials such as wood or metal to make it a centerpiece in any bedroom.

Dressers and Screens

Dressers and screens are pieces of furniture that can often be overlooked when it comes to functional art. However, they can be transformed into beautiful and practical pieces that add a touch of creativity to any room. A functional art dresser can be designed with unique shapes and patterns, while a functional art screen can be created with intricate designs and materials such as wood or metal.

Overall, furniture is a great place to start when exploring the world of functional art. With a little bit of creativity and innovation, any piece of furniture can be transformed into a unique and practical work of art.

GRIN AND BEAR IT

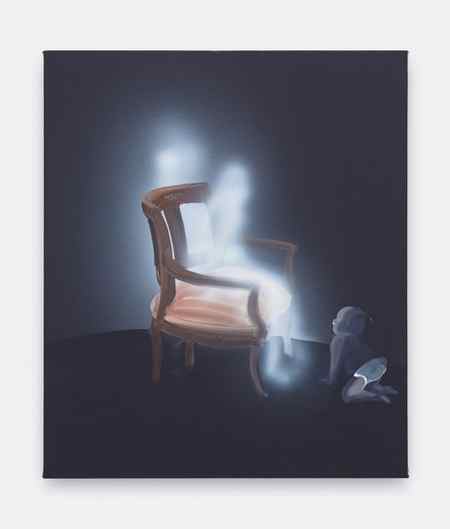

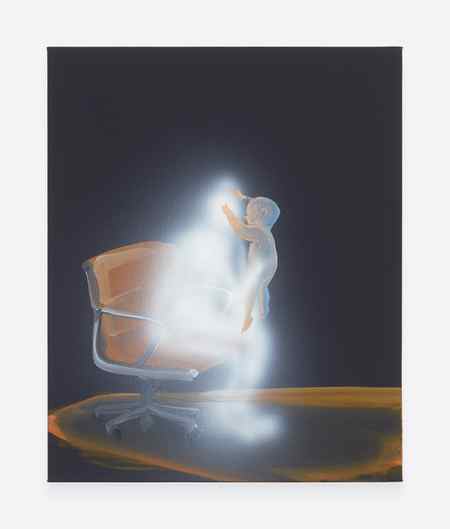

TALA MADANI’S paintings, drawings, and stop-motion animations of violent men, sadistic babies, and filth-covered moms plumb our most savage depths. To mark the artist’s first institutional survey, now on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, critic Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer weighs in on the surprising “cheerful air” and “basic beauty” that underpin the LA-based artist’s deliriously perverted tableaux.

IT STARTS PLAYFULLY with a cake in the face. Ha ha. Just a joke. Right? Birthday candles burn in eye sockets, confections rise vertically like giant phalluses or balance on the backs of men crawling on all fours. It starts, lightheartedly, with roughhousing, stupid practical jokes, a bit of cross-dressing, and juvenile body-part swapping, with ball sacks standing in for jowls. Adolescent misbehavior—scheming, giddy, irrepressible—propels the action. In Tala Madani’s earliest exhibited paintings, made around the time she completed her MFA at Yale University in 2006, groups of soft-boiled, slovenly middle-aged men gather to let loose, sharing in revelry that usually revolves around big frosted layer cakes. The men tend to be bald, with heavy eyebrows and dark facial hair, sporting exaggerated expressions that verge on Kabuki. Conjuring various scenes of buffoonery and bromance, Madani presents an imagined model of communal belonging. Her examination of homosocial dynamics promises ample pleasure: The men are nearly always grinning. In fact, the over-the-top signaling of happiness is of such concern that Madani figured the smiley-face icon itself as a leitmotif in many subsequent paintings, where it might hover like a halo over, or project like a mask onto, her characters in an aggressive, insistent way. From the beginning, she established a tension between the events and expressions depicted, scrambling presumptions around consent.

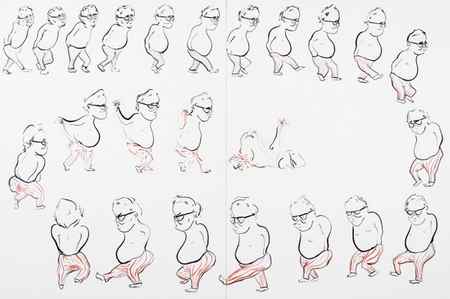

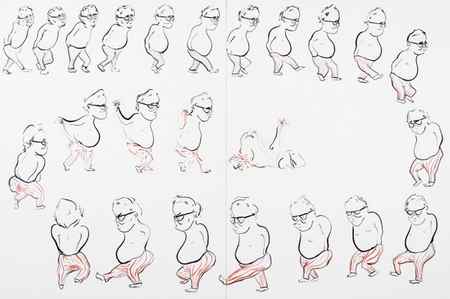

Related

The grins persist as the situations get stranger. The savagery escalates. In the paintings and stop-motion painted animations that followed that first body of work, the little men, who quickly became her signature players, venture into new interiors and experiment with new behaviors. Babies enter the picture, too, as a kind of amplification of the man-child typology. Ever more unhinged, her men soon erupt cum and blood and vomit and engage in forced enemas, belligerent golden showers, coprophagia, disembowelment, self-mutilation, decapitation, amputation, and other manners of defilement and straight-up child abuse. What may once have seemed like harmless locker-room goofs gradually grow darker, and precisely no one will be surprised to learn that boys-will-be-boys play is the stale, jizzed-over seedbed from which toxic, criminal masculinity springs. In Beards, 2015, Madani shows us an adult man half-clothed as Santa pissing through a gift box (à la Saturday Night Live) onto a bunch of babies wearing strap-on beards. In The Santas, 2012, four similar sickos wearing Santa hats and red pants dangle their dicks over the railing of a baby’s crib. In Stained Glass, 2014, two men raise wineglasses filled with blood drained from their friend’s lacerated legs, which have been shoved through broken window panes above. In the twenty-three-second video Under Man, 2012, a guy relaxing at the base of a long wall suddenly gets pummeled by a cascade of heavy objects—a brick, an iron, a pan, a boulder, barbells—thrown on top of him by two look-alikes until he finally decides to finish the job and hammers himself into a hole in the ground. In the one-minute-and-thirty-five-second Eye Stabber, 2013, a man who is covered in eyes, Argus Panoptes style, stabs each one out with a pair of scissors until his entire body withers and drains into a bloody pool in an empty parking lot. And in the painting Spiral Suicide, 2012, a bespectacled, shirtless dad type ambles centripetally around the picture’s perimeter while reaching into his pants to pull his own large intestine out from his anus and asphyxiate himself with it before falling down dead. Horrors heap upon horrors; one extreme begets another. Yet it may not be quite enough: “My work is still extremely PG, from how I would like it to be. It’s not as extreme as I want it to be, in some ways,” Madani has said.

Madani turns bodies inside out. The stretching of entrails that entails is unsettling but not disagreeable. Her men and babies make insane messes, flinging shit and piss and other base emissions all over the place. Parts tear. Paint-as-flesh drips and swirls. People jump out of their skins and anatomies evacuate. Madani is interested in bodies as ecstatically mutable and ambiguous forms. In Untitled, 2015, flashlights turned on in three men’s mouths shoot bright colored light out of their asses. One is struck, again and again, by Madani’s continued presentation of disturbance and abjection as experiences of renewal, grace, and transcendence. Looking at her paintings can be nauseating and breathtaking at once. She bludgeons her way to the sublime.

Part of what makes the scenes so transfixing is their preposterously blithe and cheerful air. For all their vulgar troublemaking, her diminutive doofuses charm us with their lack of self-consciousness, shame and inhibition. Somehow, despite all odds, these men and babies radiate sweetness. Throughout the mayhem, they enjoy themselves, and their glee in the face of outrageous affronts is confounding. Judgment hits a roadblock: There are neither obvious victims nor clear villains. Her art remains difficult to look at, but seeing the unsightly is surely one of art’s salutary functions. Whether or not it is good for you, art provides a safe space for imagining the unacceptable and thinking the intolerable: for seeing a person dismembered, a body liquefied and streaked on the walls, babies’ hands and faces smeared in feces, blood splattered on the sidewalk, a child’s penis so swollen and distended it lies on the floor like a waterlogged corpse. Yes, cartoonish violence is central to Madani’s imaginary, but more broadly speaking, beyond the gore, she also values excess and disobedience, anarchy and transgression, malfunction and innovation, humiliation and disgust. The stakes are clear. In question is the capacity for feeling for others and feeling at all. And the willingness, the eagerness, to be vulnerable and wounded.

AT THE SAME TIME, Madani’s paintings provoke laughter. One feels an eruption of awe at the audacity of her scenarios, the basic beauty of their unassuming facture, and the love she so clearly has for her adorable miscreants. Cathartic for sure and even joyful at times, the laughter is an involuntary expression of deep recognition, an aesthetic adrenaline rush: “I really laugh when I paint. Not every time, not with everything. But I do, yeah, sometimes there’s this burst of laughter and I always see it as a good sign. The laughter is quite interesting because it’s not necessarily ha-ha funny laughter, sometimes it’s a burst of energy that is laughter. You know, there’s this intensity of whatever is coming up.” Incorporating physical comedy, she structures her pictures as intuitive but fine-tuned visual jokes, crafting absurd interpersonal dramas and narrative conceits that always retain a fable-like quality. It is fairly remarkable, and says a lot about our world, that for being so nightmarish and bizarre, her paintings work well as a screen upon which to project pretty much any breaking-news story or headline. Guns, for instance, paired with babies or their making feature in a number of works, such as her animation The Womb, 2019, in which a fetus materializes a handgun to blast open the walls of the uterus after watching a highlight reel of world history, and the “Cum Shot” paintings, 2019, in which men with rifles cocked splooge white stains on chairs and a puddle on the floor where a baby plays. These hardly read as parody in the wake of this past year’s slaughter of nineteen elementary-school children and two teachers in Uvalde and the forced-birth reality in which tens of millions of girls and women live in post-Roe America. Sometimes no projection is needed at all, as in Babyocracy I, 2021, which shows men in suits frantically climbing over benches to flee the halls of Congress as a naked baby crawls on the dais. In a manner reminiscent of the pointed social commentary of figurative artists like Nicole Eisenman, William Kentridge, or Kara Walker, Madani’s dark humor is exuberant and bubbly, hopped up on something strong and wrong. Having studied political science as an undergrad, she builds on the pictorial vernacular of political cartoons: “Satire, satirical caricature, is more of a social engagement with whatever is being depicted. I do think that it would be different if I were a man painting this way,” she has said. “My work wouldn’t be read as critiquing men. It would be read as social criticism, as it has been with Honoré Daumier, James Gillray, Ralph Bakshi, William Hogarth, and many people whose work is satirical. In the history of images, satire has not been female-driven.” Of course, a critique of social ills and a critique of gender are not exactly unrelated pursuits.

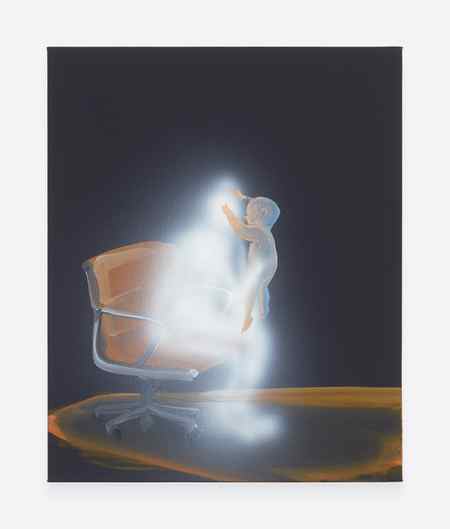

Madani’s imaginary is a realm of shadow and obscurity, blacks and grays, where darkness stands for space itself, abstract and open—the clearing for thoughts and things we thought unthinkable. Portraying interior or exterior, the darkness usually delineates a free-floating and ungrounded space, virtual and Platonic but not digital—like a blackboard. Typically blank, often horizonless or defined, as in a minimal stage set, by a single prop or feature (scissors, a gun, a chair, a table, a door, a window, a floor), her pictures’ black box is the internal theater of a skull space: “There is also no photographic reference,” she said once, “so they really depict a mental space, the mind’s eye.” Environmental elements are notational, and the undefined depth produces a shallow foreground that dispenses with perspective, a flatness she associates with non-Western painting. For Madani, who was born and raised in Tehran before moving to Oregon as a teen, abstracting pictorial space this way has had its utility, offering an escape from certain limits of lived reality. Though her men have often been taken to be generically Middle Eastern (or specifically Iranian) and the scenes themselves interpreted in light of her biography, Madani herself has actively resisted such narrow reads, feeling satisfaction when her work short-circuits expectations about her identity and background. Some years ago, she noted, “I used to have a lot of Facebook messages saying, ‘I thought you were an older gay guy. I’m so surprised you’re not.’ It was great getting those messages.”

OVER THE PAST FOUR YEARS, Madani has homed in on another kind of magic: motherhood’s impossible math. No mother can think too much about the way one’s oneness is done and undone by having babies. It makes no final sense. The simultaneous unity, dependence, and separateness of a baby forming within a pregnant body is a frustratingly irreducible fact of life that vexes the ever-raging abortion debate. How can a future body, which is really just the idea of a person, growing inside my own body, be both as much a part of me as my organs and something alien and other, destined to eject itself? That a fetus should be at the mercy of the body that makes it is clearly unbearable to the Samuel Alitos and Amy Coney Barretts of this world, triggering their not-so-repressed misogyny. Reproduction remains mind-bendingly abstract and unknowable, simply too big an idea to hold in mind, like the distance between stars, and yet so commonplace that we rarely dwell on it.

Rather, what I’ve spent more time observing is my infant’s development, imagining, when time allows, what the baby’s experience of the world might be. Initially, such thoughts are based on the union between mother and child, before progressively giving way to a burgeoning awareness of the child’s difference and distinctness, which is also the discovery of otherness and a relation to others. The process of one becoming two happens differently for mother and child, and on different timelines. Being-part-of becomes being-apart-from: a seismic transition that, though less dramatic and locatable in time, is just as essential to self-formation as the event of live birth itself. When the mother becomes other to the child, there is the natural need, or at least desire, to test the limits of where one ends and the other begins, and this testing often takes the form of abuse directed at the mother, upon whom the baby still depends. The formation of hateful feelings about the mother produces a sense of regret and an urge to repair.

Correspondingly, the psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott, by now a touchstone for the discourse around Madani’s recent bodies of work, developed the concept of the good enough mother, the ordinary devoted mother who juggles the competing demands of seeing to the baby’s needs and remaining a full person. “A mother’s love is a pretty crude affair,” he writes. “There’s possessiveness in it, appetite and even a ‘drat the kid’ element.” The good enough mother sometimes makes the child wait for what they want. The mother is not always benevolent and sweet. The mother is also harried, short-tempered, impatient, and resentful. The good enough mother sometimes loses their shit. By connecting the evolving dynamics of mothering to a child’s cognitive development, Winnicott explains that it is precisely through these natural so-called shortcomings of parents that the infant is able to gain an awareness of her independent needs and the limits of her imaginary life. Botching the job every now and then is part of doing it right.

Shit Mom, as Madani named this character and has titled numerous works and exhibitions, is a challenging figure packed with waste and containing a torrent of unnerving implications and complicated reads. She could be a “bad” mom—neglectful, irresponsible, cold, mean, or disengaged—but she might just be clumsy, forgetful, overwhelmed, anxious, on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Her shittiness could be her own self-loathing or masochistic craving, or it could be a psychic portrait of how she sees the world. It certainly personifies her children’s anal-stage compulsions run amok. Disfigured and decomposed, the Shit Mom fertilizes someone else, passing vexed inheritance from one generation to the next. She embodies rejection, resignation, and failure, the countless daily mishaps that are part of parenting. She isn’t shit, but she feels like shit. She hasn’t slept. She’s a worn-out, wasted antihero. She has let herself go.

But Shit Mom, like all Madani’s figures, functions most powerfully as a pleasurable release, a laugh that lingers and clarifies. She rings true as that private fantasy of many a mom—the temptation, amid the chaos of home life, to check the fuck out and not give a shit. Most of the time, we see Shit Mom bombarded, ripped apart, and violently reconfigured by a baby or, more often, a small horde of babies; they blast through her like she’s a tub of stale Play-Doh. But some paintings show her in repose and reverie, full of thoughtfulness, melancholy, warmth, vulnerability, and fortitude. The contours of her blobbiness protect a zoned-out zone, the shape of a being transported to another plane of existence. In Passage #2, 2019, she wades into the ocean, a solitary figure gazing at the horizon. She is a monument. She grooms a child in a trio of “At My Toilette” paintings, 2019, lost in thought, leaving a residue of brown fingerprints on her child’s neck as her hands automatically perform the familiar motions of tenderness and caress. Her face, only vaguely indicated by areas of shadow, comes to characterize her mood—blank and numb. She might or might not be depressed and experiencing a failure to bond, but who hasn’t felt vacant for long spells? A new series of large “Cloud Mommy” paintings, from this year, embed the maternal like an apparition in faraway wisps of cirrus that drift across blue skies. Motherhood is a lot like personhood; there’s room for a full range of feelings.

Across her practice, whether rendering men, moms, or babies, Madani raises basic questions of identification. Whom do we identify with? Whom does she identify with? And how, in fact, do we identify at all in the circumstances she presents? Her concern, ultimately, is the quality of concern itself as an expression of empathy for and curiosity about the other—and, above all, the self, with all its dark, dank corners.

“Tala Madani: Biscuits,” organized by Rebecca Lowery and Ali Subotnick with Paula Kroll, is on view through February 19, 2023.

Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer is a writer and curator in Los Angeles, where she runs the Finley Gallery and Pep Talk publications.