From 1911 to 1916, Matisse focused on depicting the human figure in interior spaces decorated with Eastern rugs and souvenirs. While he was not drafted during World War I, the seriousness of world events affected his painting, muting his palette. Towards the end of the war, however, he returned to his bright colors, leading to his “Nice period” from 1917 to 1930. Many of these paintings make use of the white of the exposed canvas to suggest the bright light of southern France.

Painting concepts using a blue background

Carol,

I’ve been a WetCanvas member for a number of years and, until now, it was my one and only post. Saved it all up I guess It could be a book, but in many ways its more helpful as notes. No excess verbiage to impede connections.

After I’ve had time to receive feedback on this thread, I’ll start posting the other sections which I think you’ll find just as valuable.

Keene

February 15, 2012 at 6:39 pm #526198

Default

Freesail,

That’s probably more appropriate, I didn’t find it when I first checked the list of forums. Is there a way to just move it?

February 15, 2012 at 7:38 pm #526190

Default

Keene: A (belated, I guess) welcome to WC! Thanks for the extensive info. I’ve copied it and plan to study it further.

[FONT=Arial]C&C always welcome ©[/I] [/font]

[FONT=Palatino]

“Life is a pure flame and we live by an invisible sun within us.” ― Sir Thomas Browne [/size][/font] http://s3.amazonaws.com/wetcanvas-hdc/Community/images/29-Jul-2007/85002-sig-thumbnail_composite_2.jpg]/img]

February 15, 2012 at 8:10 pm #526199

Default

Annie,

Thanks for the welcome. Belated I guess, I joined WC years ago. I see it says I joined in 2010, but that’s way off. I joined before I moved to Norcal for 4 years and I’ve been back in SoCal for almost three. I think I must have re-upped or something when I moved back south and had a new e-mail address. Anyway, hope the notes help.

February 15, 2012 at 9:58 pm #526193

Default

Hey Keene , Great Info …. of course we should post this in there, Im a Guide from Figures , so Ill post this in our staff thread and one of the mods can link it to our Library , I think it should go in there ….Cheers . D

February 16, 2012 at 4:49 am #526189

Default

Fantastic! Thanks for taking the time to compile all of this useful information.

Cheers, Donna

My Blog My Website

My Flickr Page

February 16, 2012 at 9:57 am #526195

Default

That is a lot of info to digest, thanks for the feast.

Kathie :

February 16, 2012 at 12:43 pm #526188

Default

Amazed to read that Caravaggio left out all the shadows.

Lawrence Humphrey

Torrelles, Spain

July 9, 2012 at 9:57 pm #526191

Default

Love to read all the info!I am following all your threads, thank you for posting. clap::clap:

C and C are welcome!

July 10, 2012 at 3:08 pm #526187

Default

Caravaggio would disagree with that statement.

Quite a lot of contradictory opinions.

Painters who say color is not important do not know what they are talking about.

Shadows are not always cool by comparison to warm colors but are often warm compared to a warm colors.

August 20, 2013 at 9:37 pm #526200

Default

Painting “Fundamentals” for the Advanced Artist

By Keene Wilson[/URL]

Foundation The two most important things in painting are value and design. If the foundation is strong, painting will stand up.

Ambivalence in your approach to painting will lead to an ambivalent response in the viewer.

Visualize the finished painting, know the color harmony, how the painting is to vibrate.

All paintings must have: a sense of space, design (masses must hold together abstractly), and artistic blend of strength and subtlety.

Have a general direction in mind, but don’t try to have all the answers

Chose to see in a particular way and with a consistent structural unity

Follow your feeling while painting, do most thinking beforehand

Beginners paint objects, experienced painters paint passages

Learn to subdue the natural tendency to see detail and value changes. Edit out that which doesn’t help clarify. Relationships Focus on getting the relationships right

Temperature and value relate to what’s next to it, harmony relates to the whole painting, composition relates to masses, soften edges relative to the focal point,

A color is what it appears to be only because of its relationship to the surrounding colors. When we paint, we really aren’t copying the colors of nature, we are painting the color relationships. We don’t have the color palette that nature has, so we must give the illusion of truth through the relationships of the colors we choose.

Composition

Group darks and lights and separate into a large, clear pattern, group/gradate within the pattern.

First find the nice thing about a composition, then hide it. Click to view 20 Compositions (on Pinterest)[/URL] Design

Underlying principle: Balance of vitality (contrast and opposition) with harmony. Vitality comes with use of brilliant colors, opposition of light with dark values, complementary hues and warm and cool colors. Harmony is achieved with the use of a pervading color, modifying complementaries with their opposites, and gradation of value and hue.

Think abstractly

A main objective in the art of painting is to disguise the use of methods or the influence of principles.

Be a little bit sloppy

Vary shape, direction and position, color; dramatize; sharpen points, large areas immense, small areas tiny, etc.

Design is critical – simple pattern, light/dark, color harmony, shapes, clarity/mystery, variety, contrast

Everything has gradation. Richard Schmid’s[/URL] paintings are considered highly realistic, but note how conscious he was of the abstract pattern in “Sketch of Nancy”.

presented up-side-down to emphasize the design

Editing It’s not what you leave in, but what you leave out.

Think about editing and design all along

Edit out that which doesn’t help clarify

Everything for one thing

Look for the minimum visual information then add any detail on top of that. Yet, edit out that which doesn’t help clarify

Make a decision rather than mindlessly copying what’s there

For every painting you have to decide what it is about and what kind of reaction you want.

“Pulling Together” by Skip Lawrence[/URL]

Shapes Law of fine shapes – a dynamic oblique with different measures and interlocking edges (“incidents”) – Edgar Whitney

Think big, medium, small throughout painting Color

Harmonize the whole canvas as you go – no matter what’s out there

Look for contrasts of color that you can make both interesting and believable.

Alternate warm/cool within color family throughout painting.

Color and value appear truest in the core.

Use specific colors to express specific planes. Paint complexion tones in regard to the planes assigned to them: X planes warm; Y planes cool. Click to view 20 Artists Showcasing Color (on Pinterest)[/URL] Creativity

Art happens somewhere between clarity and ambiguity, concept and intuition.

Make something clear and recognizable, then tantalize with something left to interpretation

The best art amazes us because of what the artist left out, not because of what he or she put in. Provide just enough information to start perception in the right direction, let the mind of the viewer fill in the rest. A certain lack of clarity makes paintings more interesting because if everything is revealed at a glance why look longer. The viewer will complete the painting better than you could

If your goal is technical correctness, you will probably paint tightly. Set goals such as “paint quality”, “the effect of light”, “exciting color and shape organization” to allow for a more creative approach.

It’s not about making it correct (copying) but about making it interesting

“Old Man” by Andrew Wyeth Exaggerate:

-

[*]pattern,

[*]shadows,

[*]gesture,

[*]perspective/recession,

[*]color harmony/passages,

[*]the effect of light,

[*]planes,

[*]separation between light and dark

[*]structure

[*]Don’t exaggerate the variation – look for the clear simple statement first

mixing area, after use

Drawing

Emphasize structure. Don’t allow reality to destroy structure.

Overlap is the most powerful conveyer of depth

Get the gesture right (action, proportion and balance) before moving on Value Color is mostly a matter of personal choice, but value is factual.

Don’t try to paint the values you see, but the value relationships you want.

When you’re chasing color, often it’s not the color that’s wrong, but the value.

Use as few value differences as possible, make warm and cool color changes rather than value changes

All the color within a shape value must live within that value

Initially, limit your value choices to two, three or four separate and distinct values, but later there can be subtle value differences within each value range, with each plane having its own value and temperature relative to other planes within its value range. Value Painting Process Group darks and lights and separate into a large, clear pattern, then group/gradate within the pattern.

Structure/construction; then values, “tonal solution”, initially everything flat; then draw into the tonal solution to pick out just enough to clarify what is happening; then color

Exaggerate planes and push the contrast between light and shadow

Value painting demonstration by Vadim Zang

Depicting Form Light and shadow will each have a value range which doesn’t overlap the other. Within these two values can show core shadow, cast shadow, reflected light, mid-tone and highlight.

Once you get the color and value structure laid in, think topographically using the principles of structure (not the subtle changes of form); this area goes in, this area comes out.

Use the shadow shape corner (always the “edge” nearest to you) to tell viewer where and how much the form turns.

Find the largest shapes possible within a form, simplify the form, then reduce the number of value changes needed to suggest it.

Establish the form from the model, but decide on your own color scheme. Use drawing skills and knowledge of value and temperature shifts to depict the form, but don’t paint the color you see, but rather establish the design using all aspects of color, then exaggerate color shifts to depict the form given the design.

All lighted areas should hold together as one group, as should the shadow areas. When distinguishing shadow forms, first establish how they belong together before showing how they are different.

Use value and color to describe topography (instead of copying the values and colors you see)

The right bone structure or topography will give a likeness.

Demonstration painting by Henry Yan

Brushwork Have one area with precise edges and strong value contrast (focal point), and another with compatible values and lost edges

Blend a lot but keep the colors clean in spots. Look for opportunities for lost/found edges where shapes of the same value meet.

Soften edges relative to the focal point

For brushstrokes think “power and variety”.

Use “markers” (line, shape, value, color) to keep track of where you are on the canvas without resorting to “paint within the lines”

Scraping with palette knife contrasts with thickness of brushstrokes and provides luminous and transparent effects

Contrast tight areas with loose.

Thin shadows, impasto lights.

Slow down, apply brushstroke with a descriptive purpose, and leave the stroke undisturbed

Apply each stroke as its best and final statement.

Lay in washes boldly, but put in impasto strokes slowly.

For brushstrokes think “power and variety”.

Use “markers” (line, shape, value, color) to keep track of where you are on the canvas without resorting to “paint within the lines”

Contrast tight areas with loose.

Use turpentine to thin, then wipe away with cloth

Hold brush very loosely

French gate demonstration by Ovanes Berberian

[/CENTER]

[/LEFT]

Pushing Color Harmony First establish the value range, then you can bend the temperature any way necessary

To push color, keep the value and temperature, but the color can be any color. Shadows won’t be intense even when the color is pushed.

Connect hues throughout in ways which improve the design

Palette management is critical. Complements with a blended range connecting them are harmonious whereas unblended they contrast.

Harmony is created by limiting the color choices and blending.

Harmonize a painting by either adding a touch of the light color to each element touched by the light and add colors of the opposite temperature in the shadow, or have every color lean toward a common color direction.

“Gray Whale Cove” by Elio Camacho

What to Think About Should it be lighter/darker, richer/grayer, warmer/cooler?

Different plane = different temperature and different value. Don’t, however, lose the initial color/value structure.

Paint with your idea (contrast, moody, high key, what happens to the light?) Be consistent. Rules of Thumb Blending creates harmony,

Warm/intense comes forward,

Dull/grey recedes.

Use shifts in value and temperature to convey how the form turns, but not the color you see

“Mostly, some and a bit” is the basic formula for pleasing color schemes.

Use/invent a single light source.

Analyze, Don’t Copy

When in doubt, simplify.

Initially, the two, three or four values are separate and distinct, but later there can be subtle value differences within each value range, with each plane having its own value and temperature relative to other planes within its value range.

Design, using severe grouping into 2, 3 or 4 values and 5 or 6 shapes.

[/LEFT]

“Last Road of the Day, Study 3” by Steve Huston

Process Start Take care of patterns before any details.

Start with flat shapes. Just focus on accurate values and color temperatures.

Lay in the darks with variation between warm and cool darks with spots of great, pure color, yet surrounded by subtle grays. Blend a lot but keep the colors clean in spots. Look for opportunities for lost/found edges where shapes of the same value meet.

For as long as possible, focus on passages, no detail and no modeling

Search for the correct color relationships. Middle Blend frequently to get the correct colors and values. Later lay thicker paint on top with obvious brushstrokes where emphasis is needed

Refine shapes with temperature, not value.

Look for gradation and core shadows

Keep the lights as near the same value as possible; keep the mass that is in shadow, always in shadow, and make differences by gradations in color

“Rest in Harvest” by William Adolphe Bouguereau

Finish “Paint the painting” purely to improve the design and enhance the effect

Make creative choices using the scene merely as a reference.

“Finish” is not more detail, but a little bit of enhancing and a lot of softening/subtlety.

“Backlit Flowers”, “Exuberance” and “Gonna Get Wet” by Keene Wilson[/URL] Further Reading: Color Composition Design Drawing Plein Air Painting Concepts and Techniques Vision and Light Artists Revealing Their “Secrets”

Summary of Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse is widely regarded as the greatest colorist of the 20 th century and as a rival to Pablo Picasso in the importance of his innovations. He emerged as a Post-Impressionist, and first achieved prominence as the leader of the French movement Fauvism. Although interested in Cubism, he rejected it, and instead sought to use color as the foundation for expressive, decorative, and often monumental paintings. As he once controversially wrote, he sought to create an art that would be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair.” Still life and the nude remained favorite subjects throughout his career; North Africa was also an important inspiration, and, towards the end of his life, he made an important contribution to collage with a series of works using cut-out shapes of color. He is also highly regarded as a sculptor.

- Matisse used pure colors and the white of exposed canvas to create a light-filled atmosphere in his Fauve paintings. Rather than using modeling or shading to lend volume and structure to his pictures, Matisse used contrasting areas of pure, unmodulated color. These ideas continued to be important to him throughout his career.

- His art was important in endorsing the value of decoration in modern art. However, although he is popularly regarded as a painter devoted to pleasure and contentment, his use of color and pattern is often deliberately disorientating and unsettling.

- Matisse was heavily influenced by art from other cultures. Having seen several exhibitions of Asian art, and having traveled to North Africa, he incorporated some of the decorative qualities of Islamic art, the angularity of African sculpture, and the flatness of Japanese prints into his own style.

- Matisse once declared that he wanted his art to be one “of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter,” and this aspiration was an important influence on some, such as Clement Greenberg, who looked to art to provide shelter from the disorientation of the modern world.

- The human figure was central to Matisse’s work both in sculpture and painting. Its importance for his Fauvist work reflects his feeling that the subject had been neglected in Impressionism, and it continued to be important to him. At times he fragmented the figure harshly, at other times he treated it almost as a curvilinear, decorative element. Some of his work reflects the mood and personality of his models, but more often he used them merely as vehicles for his own feelings, reducing them to ciphers in his monumental designs.

The Life of Henri Matisse

Matisse meticulously experimented with art, trying and retrying ideas saying: “I have always tried to hide my efforts and wished my works to have a light joyousness of springtime which never lets anyone suspect the labors it has cost me.”

Read full biography

Read artistic legacy

Important Art by Henri Matisse

Progression of Art

1904-05

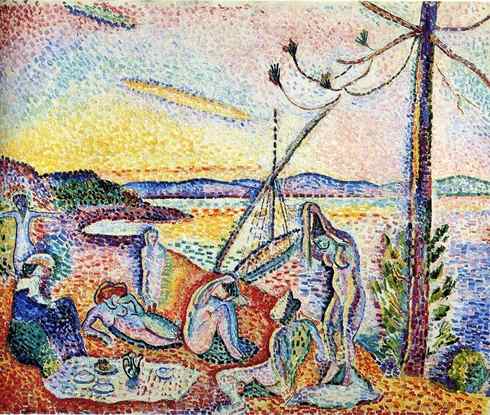

Luxe, Calme, et Volupte

The title of this painting is taken from the refrain of Charles Baudelaire’s poem, Invitation to a Voyage (1857), in which a man invites his lover to travel with him to paradise. The landscape is likely based on the view from Paul Signac’s house in Saint-Tropez, where Matisse was vacationing. Most of the women are nude (in the manner of a traditional classical idyll), but one woman – thought to represent the painter’s wife – wears contemporary dress. This is Matisse’s only major painting in the Neo-Impressionist mode, and its technique was inspired by the Pointillism of Paul Signac and Georges Seurat. He differs from the approach of those painters, however, in the way in which he outlines figures to give them emphasis.

Oil on canvas – Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris

1905

The Woman with a Hat

Matisse attacked conventional portraiture with this image of his wife. Amelie’s pose and dress are typical for the day, but Matisse roughly applied brilliant color across her face, hat, dress, and even the background. This shocked his contemporaries when he sent the picture to the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Leo Stein called it, “the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen,” yet he and Gertrude bought it for the importance they knew it would have to modern painting.

Oil on canvas – The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

1905-06

Joy of Life (Le Bonheur de Vivre)

During his Fauve years Matisse often painted landscapes in the south of France during the summer and worked up ideas developed there into larger compositions upon his return to Paris. Joy of Life, the second of his important imaginary compositions, is typical of these. He used a landscape he had painted in Collioure to provide the setting for the idyll, but it is also influenced by ideas drawn from Watteau, Poussin, Japanese woodcuts, Persian miniatures, and 19 th -century Orientalist images of harems. The scene is made up of independent motifs arranged to form a complete composition. The massive painting and its shocking colors received mixed reviews at the Salon des Indépendants. Critics noted its new style — broad fields of color and linear figures, a clear rejection of Paul Signac’s celebrated Pointillism.

Oil on canvas – The Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

1907

Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra)

Matisse was working on a sculpture, Reclining Nude I, when he accidentally damaged the piece. Before repairing it, he painted it in blue against a background of palm fronds. The nude is hard and angular, both a tribute to Cézanne and to the sculpture Matisse saw in Algeria. She is also a deliberate response to nudes seen in the Paris Salon – ugly and hard rather than soft and pretty. This was the last Matisse painting bought by Leo and Gertrude Stein.

Oil on canvas – The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection

1908-09

The Back I

Although Matisse is known above all as a painter, sculpture was also important to him, and he was particularly inspired by Auguste Rodin, whom he visited in his studio in 1900. The Back I is the first of a series of four large relief sculptures that Matisse worked on between 1909 and 1931, all of which are significantly innovative. Conventionally, the background of a relief sculpture is regarded as a virtual plane, a kind of imaginary space that the viewer fills in with his own notions. But in The Back series, Matisse suggested that the backdrop was fashioned from the same heavy material as the figure itself. Throughout the series, the figure is progressively simplified and further identified with the background. The motif was possibly first inspired by a figure in a painting by Cézanne that Matisse owned.

Bronze – The Museum of Modern Art, New York

1915-16

The Moroccans

Matisse planned this picture as early as 1913, and it recalls visits made to Morocco around this time. A figure sits on the right with a back to us, fruit lies in the left foreground, and a mosque rises in the background beyond a terrace. Matisse said that he occasionally used black in his pictures in order to simplify the composition, though here it undoubtedly also recalls the stark shadows produced by the strong sunshine in the region. Like Bathers by a River (1917), The Moroccans was significantly influenced by Picasso’s Cubism, and some have even compared it to Picasso’s Three Musicians (1921). Although it employs the same brilliant color as much of Matisse’s work, its use of abstract motifs and rigid diagrammatic composition is unusual, and has attracted considerable speculation. Rather than use the scene as an opportunity for decoration, it is as if Matisse has tried to find the means to chart and map it.

Oil on canvas – The Museum of Modern Art, New York

1917

Bathers by a River

Matisse regarded this picture as one of the most important in his career, and it is certainly one of his most puzzling. He worked on it at intervals over eight years, and it passed through a variety of transformations. The painting evolved out of a commission from Matisse’s Russian patron, Sergei Shchuckin, for two decorative panels on the subjects of dance and music, and, initially, the scheme for the picture resembled the idyllic scenes he had previously depicted in paintings such as Joy of Life (1905-06). However, his transformations gradually turned it into more of a confrontation with Cubism, and it is for this reason that the picture has been the subject of intense scrutiny. Although Matisse rejected Cubism, he certainly felt challenged by it, and this picture – along with many he painted from 1913 to 1917 – seems to be influenced by the style, since it is very unlike his previous, more decorative work. It is far more concerned with faithful representation of the structure of the human figure, and its position in space. The painting might be compared to The Backs series (1909-31), which also preoccupied Matisse the years he was working on Bathers, since both address the problem of depicting a three-dimensional figure against a flat background.

Oil on canvas – The Art Institute of Chicago

1932

The Dance II

Albert Barnes, a doctor and art lover, commissioned Matisse in 1931 to paint a mural for the main hall of his gallery housing works by Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and others. Matisse created a maquette for the mural out of cut paper, which he could rearrange as he determined the composition. However, the finished work was too small for the space due to being given incorrect measurements. Rather than add a decorative border, Matisse decided to recompose the entire piece, resulting in a dynamic composition, in which bodies seem to leap across abstracted space of pink and blue fields.

Oil on canvas – Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

1952

Blue Nude II

Matisse completed a series of four blue nudes in 1952, each in his favorite pose of entwined legs and raised arm. Matisse had been making cut-outs for eleven years, but had not yet seriously attempted to portray the human figure. In preparation for these works, Matisse filled a notebook with studies. He then created a figure that is abstracted and simplified, a symbol for the nude, before incorporating the nude into his large-scale murals.

Gouache-painted paper cut-outs – Private Collection